New Jersey, Northern New Jersey in particular, has a rich and location-

specific culture that can oftentimes confuse out-of-staters. New Jerseyans say “down the shore” when referring to the beach, order “gabagool” at

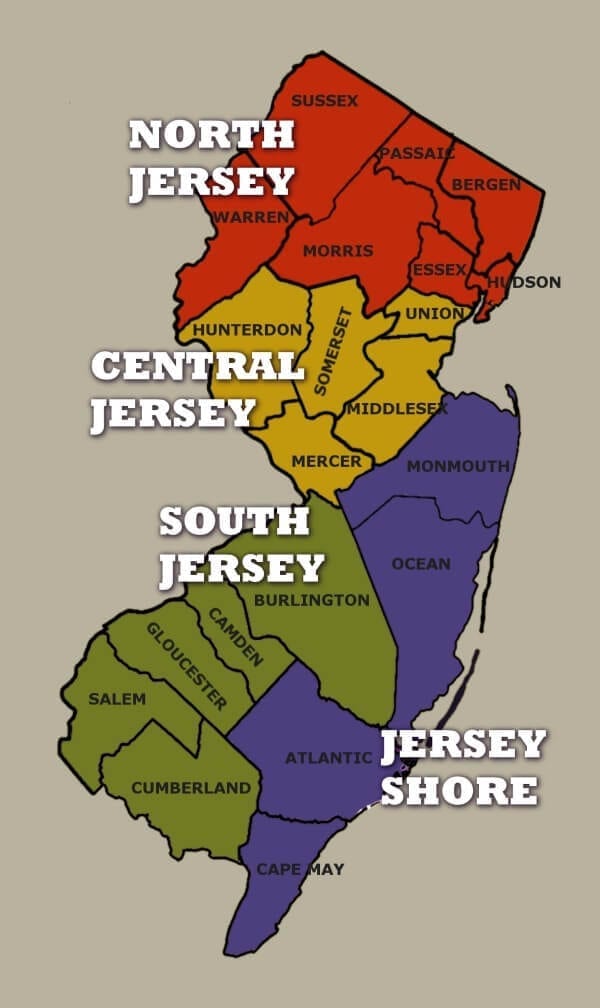

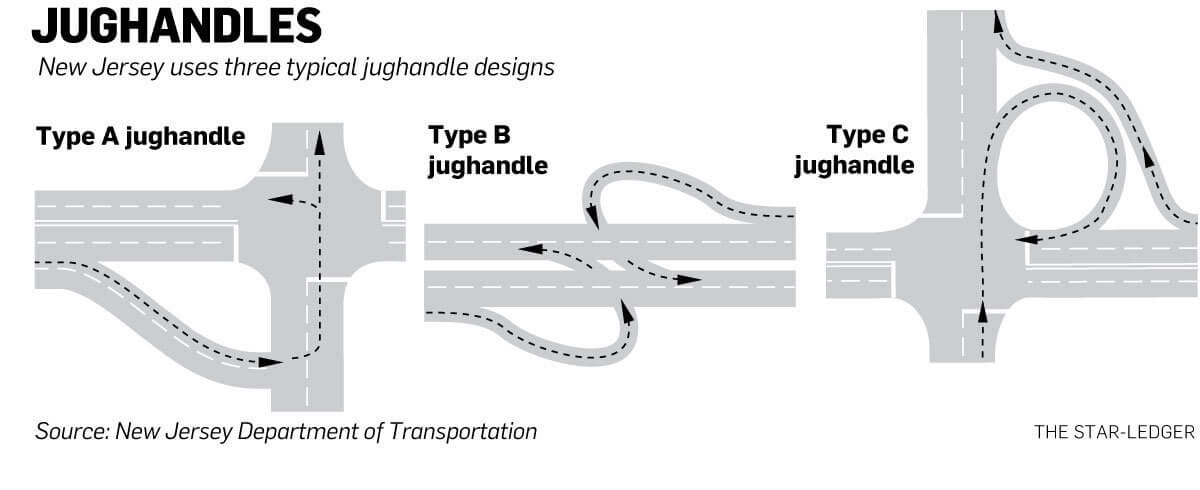

mom-and-pop Italian restaurants, and curse out Pennsylvania plates who get confused on the highway at the concept of “jug-handles.” We celebrate “mischief night” the night before Halloween, and order “disco fries” at diners. We, in North Jersey, call it “taylor ham” instead of pork roll, and notoriously order it as “taylorhameggandcheesesaltpepperketchup” at the counter of the deli.

mom-and-pop Italian restaurants, and curse out Pennsylvania plates who get confused on the highway at the concept of “jug-handles.” We celebrate “mischief night” the night before Halloween, and order “disco fries” at diners. We, in North Jersey, call it “taylor ham” instead of pork roll, and notoriously order it as “taylorhameggandcheesesaltpepperketchup” at the counter of the deli.

Despite not having obvious differences in appearance or speech from residents many other states, and even fewer between Staten and Long Island residents, there is definitely a sense of out-of-staters being placed under a monolith of “other.” In the summer, people will complain about “bennys,” a term for out-of-staters who congest the parkway and other highways while flocking to the shore for their week-long rentals. I have extended family in Wyoming and Lackawanna Counties, Pennsylvania, and they’re colloquially known within my family as the “Pennsylvania boys,” or the “Pennsylvania side,” and when we visit them, we drive across the Delaware Water Gap into “Pennsyltucky.”

Despite being right across the river, a resident of Hoboken, Jersey City, or even West New York would never say they they live in a NYC suburb. New Yorkers who drive into Jersey for games or concerts at Metlife Stadium might be mocked for claiming a stadium and teams who play and exist solely in East Rutherford. We claim Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, though New Yorkers might say otherwise, and Bruce and Sinatra are uniquely ours. There is competition with New York and Connecticut over who has the best bagels, the best pizza. North Jersey claims NYC as “the city,” though in South Jersey that epithet may refer to Philadelphia.

Despite being right across the river, a resident of Hoboken, Jersey City, or even West New York would never say they they live in a NYC suburb. New Yorkers who drive into Jersey for games or concerts at Metlife Stadium might be mocked for claiming a stadium and teams who play and exist solely in East Rutherford. We claim Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, though New Yorkers might say otherwise, and Bruce and Sinatra are uniquely ours. There is competition with New York and Connecticut over who has the best bagels, the best pizza. North Jersey claims NYC as “the city,” though in South Jersey that epithet may refer to Philadelphia.

Despite this specific culture, a lot of which derives from the North Jersey Italian diaspora a la The Sopranos, New Jersey transplants will be accepted into the community as long as they proudly claim it home. The distinguishment of “others” generally refers to travelers–especially in the summer–or commuters.

My perception of out-of-staters is usually general frustration, especially on the road. Despite knowing NJ highways can be highly confusing to out-of-

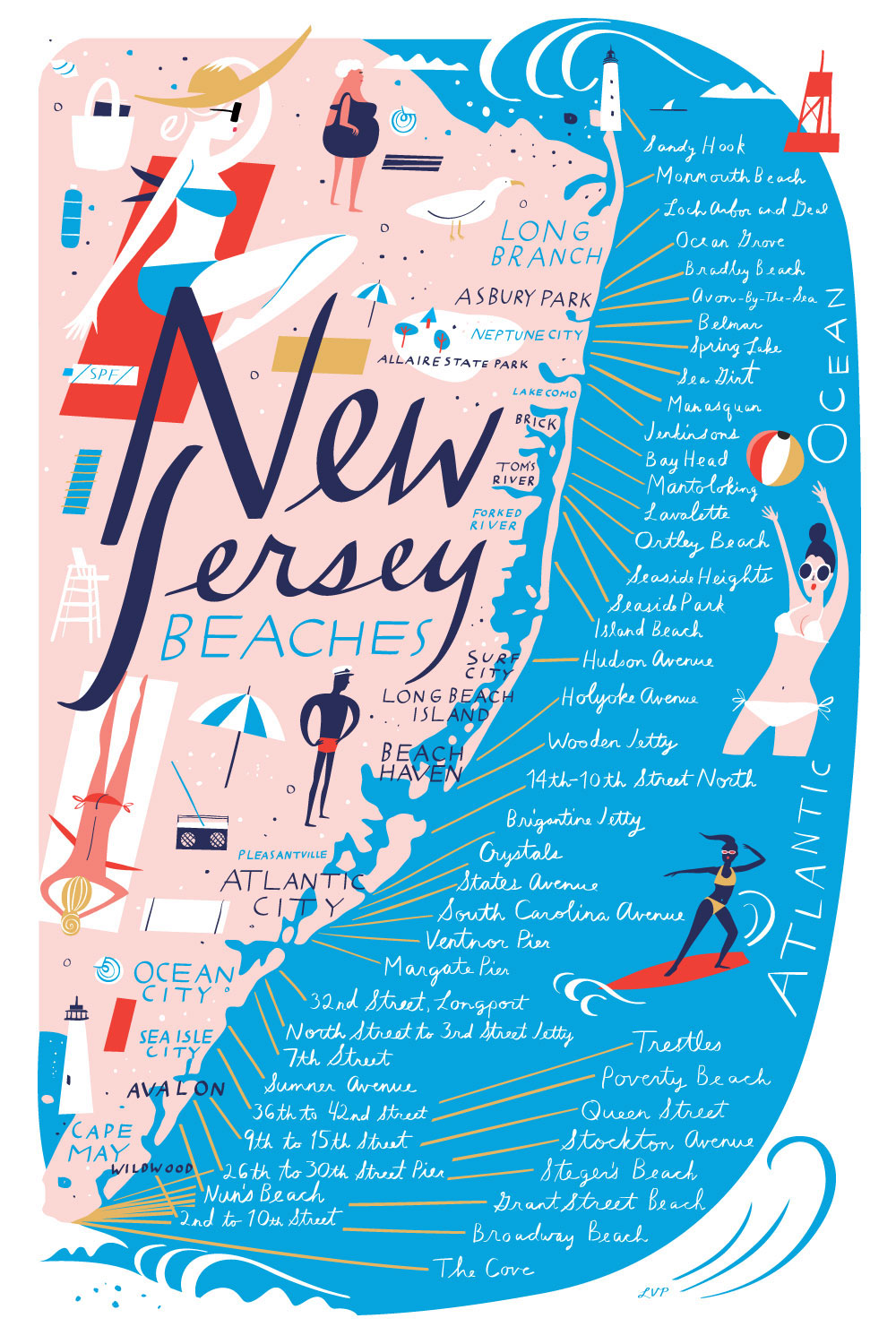

state drivers, I complain when they’ll cut me off in an exit-only lane, or when they go the speed limit (or under) in any lane but the right-hand one(a Jersey faux pas). I am proud of the Jersey Shore, and truly think it is one of the greatest stretches of coastline in the United States, though I get frustrated when popular public beaches like Seaside Heights or Long Branch are congested with Pennsylvanians.

state drivers, I complain when they’ll cut me off in an exit-only lane, or when they go the speed limit (or under) in any lane but the right-hand one(a Jersey faux pas). I am proud of the Jersey Shore, and truly think it is one of the greatest stretches of coastline in the United States, though I get frustrated when popular public beaches like Seaside Heights or Long Branch are congested with Pennsylvanians.

With Pennsylvania in particular, I think New Jersey attitudes are shaped partly by classism. New Jersey is one of the wealthiest states in the U.S., and most workers are white collar and have college degrees. Even the casual phrase “Pennsyltucky” places a negative connotation on rural, working class areas, especially the Appalachian region. Being aware of the vast history and contexts behind culture, slang, and attitudes can help one be more conscious of their language, and how these “others” might perceive it.

New Jersey is not exactly known as a friendly state with friendly residents, and I think “othering” contributes to that. In North Jersey, I think perceptions shaped by The Sopranos, Jersey Shore, Real Housewives, and real life mafioso-types only contribute to this perception. In “othering,” our attitudes also shape this perception, which in turn continues to reinforces it.

In studying the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), it is critical to be aware of “othering.” Residents of MENA might be demographically different than “home” communities of many in the class, though they should not be perceived as a collective “other,” because it diminishes their individuality as community members of groups of their own, ones a lot more localized than being a resident of MENA. There are many distinct communities and groups in MENA that should be studied individually and not collectively. Assumptions should not be made about the region in whole because it ignores the region’s vast diversity. Also, the very concept of “othering” places focus on the differences between people and groups, rather than the similarities, which can lead to a higher level of depersonalization and division.

Being aware of “othering” is a crucial step in understanding its effects, especially if they lead to negative stereotyping and prejudice.