In the final two chapters of Eli Clare’s, Exile and Pride, he examines depictions of disability and gender intertwined with expressions of sexuality. It’s quite impressive how Clare is able to weave each of these topics together in all their complexities. In the chapter “reading across the grain” he discusses how disabled people are often treated as “asexual undesirables,” (Clare 130) and advocates for normalizing disabled sexuality to the point that disabled people can see themselves as sensual rather than “broken, neglected, medicalized objects of pity,” (Clare 137)

This point brings up a potentially difficult question to answer, which is this: is Eli Clare giving too much power to society’s depiction of disabled people? Should it matter to disabled people what able-bodied people have to say about disability? My answer to these questions, and likely Clare’s answer as well, is that because disabled people are so often pitied and treated as lesser than, depictions that break that common, discriminatory mold are often seen as triumphant. It speaks to Clare’s definition of the word “disability” from earlier in the book, which characterized disability as society’s failure to accept/accommodate for different identities and/or impairments.

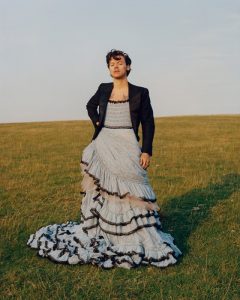

These points about the significance of depiction are brought home in Clare’s final chapter, “stones in my pockets, stones in my heart.” The moment in this chapter that stood out most to me was the story Eli Clare tells on pg. 146. Clare recounts a time when he had an artist draw a picture of him, and goes on to talk about how that depiction was significant. During that time, Clare was still often read as a girl, both by his parents and by most people around him. However, Clare’s mother tells him about an experience she had when running into the artist later. When she tried to thank the artist (Betsy Hammond) for the portrait she had drawn for her eldest daughter at the carnival, she was confused and asked “Didn’t I draw your son?” After hearing this story from his mother, the portrait gained a new significance for someone trying to come to terms with their gender identity, and Clare completes the story by reminiscing about how she, “looked again and again at the portrait, thinking, ‘Right here, right now, I am a boy.” (Clare 146)

The story Clare tells here brings up a very important point about the depiction of different genders, disabilities, and sexualities. The portrait is significant to Clare because the artist saw her the same way he saw himself: as a boy. The joy he feels when he looks at the portrait does not come from solely the depiction itself, but from the validation of identity that comes with it.