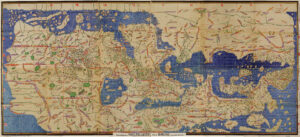

Placing the itinerary of The Travels of Sir John Mandeville within the visual context of the Hereford Mappamundi helps to alleviate the confusing nature of both sources, independent of one another. While John Mandeville speaks to the importance of various places, the Mappamundi emphasizes the visual authority of a given person, group of people, or place. Nonetheless, both serve the same function of showing a Medieval Christian audience the far-reaching influence of Christianity in the known world.

Mandeville places his origin in St Albans, a city north of London and west of Hereford, where the Mappamundi has been on display for centuries. The origin of both the map and the text being in such close proximity to one another underscores their connection. With that being said, neither the Mappamundi nor Mandeville emphasizes England within the context of the known world. Mandeville seldom mentions his home country or its government, while the Mappamundi presents England as nondescript and sans marvels–a contrasting portrayal compared to other locations.

Constantinople is the first place Mandeville truly travels, receiving attention on account of its relevance to the author, who claims to be a Christian pilgrim. Mandeville predicates Constantinople’s importance on its Christian relics, in addition to the Church of Santa Sophia and its accompanying sculpture of the Emperor Justinian I. The Mappamundi includes Constantinople as well, labeling its location alongside a structure reminiscent of the Church of Santa Sophia. The continuity of the Church in both Mandeville and the Mappamundi highlights its status as a holy site within the Christian mind.

The Hereford Mappamundi includes a myriad of Greek islands and cities, just as Mandeville enumerates in his travel account–Ephesus and Patera among them. Mandeville’s convention when describing Greek territories is to accentuate the difference between Greek Christians and his own concept of Christianity. Furthermore, he simultaneously recounts regional myths and Christian history, framing the intersection of pagan and Christian ideologies in the Medieval Mediterranean. There are several Classical references throughout the Mappamundi, complicating its function as a Christian storytelling device. These allusions, in tandem with Mandville’s own Classical education, reveal the literacy of both sources’ intended audience.

For Mandeville, Cyprus is an extension of his commentary on Greece as he highlights its strong Christian government, in addition to several holy sites on the island. He marks Cyprus as a crucial stop for travelers on their way to Jerusalem, and yet, the Mappamundi does not give Cyprus the same visual importance. Instead, it is largely unidentifiable, as the map seeks to spotlight marvels.

Another significant piece of continuity between The Travels of Sir John Mandeville and the Hereford Mappamundi is the placement of Jerusalem at the physical center of each source. Mandeville traces multiple routes to the Holy Land, while also addressing all of the Biblical and historical connections to the region. Similarly, the Mappamundi carves out space to showcase the crucifixion as well as a compass at Jerusalem. This strategic visual reminds the viewer what is most important: Christ.

The geography of Sicily in relation to Babylon is misconstrued by Mandeville and the Mappamundi. Both the text and the map mislabel Sicily’s location. Mandeville asserts that in order to get to Babylon, one must pass through Sicily, which is geographically counterproductive. On the other hand, the Mappamundi places Sicily west of Rome and south of Crete, neither of which are accurate. Its inclusion speaks to its importance within the Mediterranean world, but its misinterpretation–across both sources–demonstrates that neither Mandeville nor the craftsmen of the Mappamundi have acute geographical knowledge.

Egypt is a significant arena for marvels in the Mappamundi, which is aptly echoed in Mandeville’s account. The most fascinating parallel is the presence of a fauna on the map, and Mandeville’s anecdote about a half-goat, half-man being he allegedly encounters in Egypt. This is a blatant instance of Mandeville compiling content from other sources in his travel writings. That being said, Egypt is where Mandeville first describes people with dark skin. The Mappamundi does not focus on identifying ethnic or religious groups by skin color, but instead by physical characteristics, often represented through extremes and deformities.

India is an additional location where Mandeville and the Mappamundi overlap. Numerous times throughout his account, Mandeville describes the various people he meets with physical differences–one which being people with one large foot that encompasses their entire body. The Hereford Mappamundi has an illustration that perfectly coincides with Mandeville’s writing, in the same location: India. Similar to Egypt, Mandeville likely borrowed his description from the prior drawing on the Mappamundi.

Mandeville’s section on the Land of Gog and Magog is an extension of the anti-Semitic imagery depicted in the Hereford Mappamundi. In his writing, Mandeville asserts that the Land of Gog and Magog is where the Ten Tribes reside in the Caspian Mountains, labelling them as evil and inhumane. Additionally, he notes the numerous gryphons native to the region, which are also present within the map. The Mappamundi itself is full of various stereotypes of Jewish people, including Moses with horns and Jews worshipping a calf. These portrayals reflect the deep disdain certain Christian sects felt towards Judaism. The placement of Gog and Magog in the far East within both sources further ‘others’ the Jews they are intending to depict. Although Mandeville’s text and the Mappamundi are intended for a Christian audience, they are marred by their staunch anti-Semitism.

The legend of Prester John is pervasive throughout various Medieval travel accounts and narratives. Mandeville himself falls into the trope, repeatedly alluding to Prester John, before finally describing him and his palace in Babylon. Prester John’s wealth and abundance is heavily emphasized by Mandeville. There are a few instances in which Mandeville references the Tower of Babel, but it is not a major talking point for him. On the other hand, the Mappamundi identifies Babylon by the Tower, emphasizing its function as a Biblical setting rather than settling for the city’s connection to a fictional person.

Both The Travels of Sir John Mandeville and the Hereford Mappamundi have several shared narratives, images, and stereotypes. Each source reinforces the function of the other, helping the audience to understand what it means to be a Christian in 14th century Europe. The spatial awareness of those in this era was broadly limited, and yet, to know about a different place, in any capacity, distinguished oneself. That being said, the target audience members for both the text and the Mappamundi were Christian, English people equipped to read, write, and work. The prospect of journeying to such faraway places like Mandeville was impossible to most. Thus came the ability to pursue a mental pilgrimage alongside this book and this map.