Mapping Ibn Battutah: Ibn Battutah Medieval Map — Dailey (Editing)

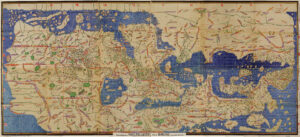

Ibn Battutah spends the second section of his account traversing Syria, venturing from modern day Cairo, Egypt to Hama, Syria, and beyond. Nearly all of his travels have been confirmed by scholars of the Middle Ages, which allows for modern scholars to map his journey with great accuracy. However, to gain more insight into how Battutah himself would have conceptualized the world of his travels, it is helpful to view his journey on a Middle Age source. The Tabula Rogeriana, created by Muhammed al-Idrisi in 1154, continued to be the most accurate and detailed world map through Battutah’s time (he departed in 1325). The Tabula Rogeriana would have likely been a well-circulated and widely utilized resource for Battutah and his contemporary travelers. Mapping his journey, particularly the first ten stops he makes after his departure from Cairo, onto a map of his time provides a greater understanding for where he would have situated himself in the world, his belief systems, and his travel hardships.

In viewing the two mappings of his journeys, the middle age and modern, alongside each other, we can make a distinction concerning religious authority in the two different time periods based on characteristics of the maps themselves. The most obvious is in the maps’ orientations. The Tabula Rogeriana is rotated upside down to how we now understand the world to be oriented, with the South pointing to the top. But, of course, in Battutah’s time, this made an equal amount of sense as our contemporary orientation. While our modern map is more scientifically based and pulls its orientation from things like knowledge about the earth’s rotation, magnetic poles, etcetera, Muslim maps in the 12th-14th centuries were ruled by religious belief. This is primarily due to the holiness of the city of Mecca. Muslims often lived north of the city, and so going south towards Mecca was seen to be the most correct orientation, associating the upward direction with righteousness toward Heaven. Similarly, the imagined Hell as being cold rather than modern interpretations of Hell as hot. This would orient North downward, as the further North you went, the closer, in theory, you would travel to the underworld. Modern maps are absent of religious influence and rely entirely on geography (though, it could also be argued that current divisions of land are intertwined with religion and politics, but as far as land mass and coordination itself, these things are absent).

The division of climes present in the Tabula Rogeriana is another dividing factor between it and the modern map. The Tabula Rogeriana divides the world into seven climatic regions. Ideas about race, religion, and geography through the lens of Abrahamic religion often regarded those climes closer to the center as more agreeable, both in land and climate as well as in inhabitants. It is interesting that nearly all of the points mapped on this section of Battutah’s journey are pinpointed in the 3rd clime, with the first being the southmost. Though he journeys far and wide, he doesn’t leave the “comfort” of these climes. When he begins to travel out of these agreeable bounds, his discomfort around people different than him grows. Many of these locations are also holy – consider his decision to travel inland to visit areas from Hebron to Jerusalem. For the medieval traveler, this would mean that clearly based on geography alone, this area was indeed the holiest and best, and this would have reinforced their belief of Islam as the dominant, most correct religion. This also raises interesting questions about what Battutah would have thought his own biological makeup (though the same ideas about biology did not exist). Tangier similarly lies in the third clime. It is possible that based on these geographic details that oriented both the most holy places in Islam and his own country he would have found himself to be the same level of agreeable and well bred as those near the holy cities.

The two maps side-by-side also highlight interesting differences between what locations are mapped versus what are not. The modern map seems to more accurately reflect some of Battutah’s fascinations with certain cities, notably Cairo. It is interesting that Battutah seems to assign so much reverence and excitement surrounding Cairo that one would assume would be reflected by a contemporary map as a notable city, especially concerning it lies somewhat near the coast and would have been easier to access. Yet, there is no mention or direction to Cairo on the Tabula Rogeriana. We know by its inclusion on the modern map that its influence has long survived and that it has been the sort of breathtaking, powerful city since Battutah’s time. Yet, we only visually see its representation when we view the modern map. I wonder if Cairo flourished greatly between the creation of the Tabula Rogeriana in the 12th century and Battutah’s 14th century travels.

The modern map also more clearly highlights why Battutah would have stayed so close to the coast through its immense detail of mountain ranges, which visually hold less of a significance and do not seem as much of a hindrance on the Tabula Rogeriana. From a medieval standpoint, coastal travel would have been preferable because inland would have constituted the unknown. We visually see this on the Tabula Rogeriana with the sparsity of mapped locations inland. While the mountain ranges are highlighted well, their scale is a bit different to the modern. The detail and accuracy of the modern map shows just how aggressive these locations could be. On the Tabula Rogeriana, they seem frustrating at most based on visuals alone. The mountains are much closer to the coast on the modern map of well, which more accurately showcases the necessity of not venturing inland. Viewing this sector of Battutah’s travels on two different maps allows one to fully grasp the travel choices that Battutah made and how they were shaped by the world around him, as well as allowing us to examine the exponential ways that travel and cartography have developed and become methodic in recent centuries.