When trying to understand the confusing account of John Mandeville’s fantastic journey, it can be helpful to use a map from the period. The Mappa Mundi found in Hereford cathedral is useful for this purpose, being composed roughly contemporaneously with Mandeville’s The Book of Marvels and Travels. The writer of the Travels never actually visited the places he wrote about, and surely was working from sources similar to the Hereford Mappa Mundi. Putting both documents in conversation with each other, as well as a modern map, reveals several things about the mentality of people in the Middle Ages. The Hereford map distorts distance, heavily favoring the holy land and giving it prime place in the Christian worldview, as opposed to modern maps which aim for accuracy. The map also includes mythic and other classical knowledge, acting as a collection of information on what one can find in certain locations where modern maps tend to emphasize geography.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi, as well as Mandeville’s Travels, are thoroughly influenced by the Christian worldview of their respective makers. One can easily see this in how the Mappa Mundi presents geography and distance. The holy land takes up an absolutely massive amount of space, almost as big as Europe, which far outstrips its actual size in reality. Hereford’s Mappa Mundi does not pretend to give an accurate size, instead emphasizing the region’s importance within the Christian imagination. Supporting this is the Mappa Mundi’s subject matter. The world is covered in stories from the Bible, such as Noah’s Ark resting on Mount Ararat, the path Moses took the Israelites, and the centerpiece of Jesus’ Crucifixion on Mount Calvary. No wonder then that the Levant, the location of most of the Bible’s contents, takes up so much importance and space. Mandeville’s Travels does something similar. Throughout the book, its author is focused on the religious nature of the places he describes. From recounting miracles and informing readers about where to find relics, to when possible recalling the actual places certain biblical events took place, such as where to see the burning bush or where Jesus performed certain miracles. When in the holy land itself, this is the majority of Mandeville’s descriptions.

Also, both place Jerusalem in the center of the world, with the Hereford Mappa Mundi doing so in a quite literal sense. Mandeville agrees with this interpretation, describing in his section on India how that city is at the center of the world and travelers from everywhere else must climb up towards it. In his cosmology Jerusalem is both the center and at the highest point in the world to which all others ascend. Mandeville finds validation about this in a passage from Psalms where David says ‘God wrought salvation in the midst of the Earth,’ which he, and other Christians as evidenced by the Hereford map, took literally. This is a departure from modern maps. Jerusalem is not the center of the world, nor are our maps covered in Biblical allusions. Modern maps seek to emulate distance as accurately as possible to aid navigation, shrinking the holy land from its prominent place to a small bit of land on the Mediterranean. Despite this modern maps, as a necessity of projecting a sphere in 2D, must include some distortion. The popular Mercator projection has been criticized for making Europe seem far bigger than it is, and places like Africa smaller. Even though the overt Christian bias has been removed, mapping still requires a choice of what parts of the world to emphasize.

Along with Biblical stories, both the Hereford Mappa Mundi and Mandeville’s Travels include references to classical knowledge and myth. Mandeville’s travels on the map would take him past the ancient city of Troy, and the Labyrinth on Crete. In the book he similarly makes reference to ancient figures like Hermes Trismegistus and Hippocrates, as well as recounting fantastic stories about monstrous heads that destroy cities and maidens turned into dragons. Similarly, both include many of the monstrous races said to live in the terra incognita such as the Sciopodes and Blemmyes reported by ancient sources like Pliny the Elder. This allows both works to serve an encyclopedic purpose, acting as a collection of knowledge about the world for their audiences which, as evidenced by their similarities, were quite similar. Modern maps, on the other hand, eschew this. Most commonly they emphasize strictly geographical information, such as terrain features, distances, and the like as opposed to the catalogue of places, lore, and creatures that populate the world.

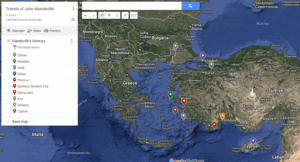

Mapping Mandeville’s journey on Modern and Medieval maps reveal different things based on different purposes. Medieval maps like the Hereford Mappa Mundi are repositories of various information including Biblical and ancient stories and the various peoples inhabiting far away places. Mandeville’s Travels serves a similar function for the prospective pilgrim to Jerusalem, meaning the two synergize well. Modern maps, on the other hand, emphasize geographical accuracy above all. Tracing Mandeville’s travels on a modern map allows one to see things like how far it would take to get from point a to point b or how difficult the terrain would be to traverse. Doing so on the Hereford Mappa Mundi allows one to see what Mandeville thought he would encounter on that journey, and just how central the pilgrimage was to the Christian mind.

Modern Map of Mandeville’s Travels:

Link to Mandeville’s Travels on the Hereford Mappa Mundi: