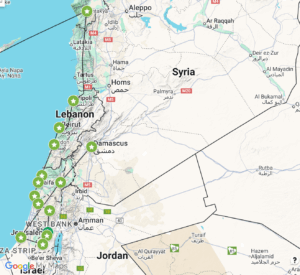

The Tabula Rogeriana, completed in 1154, was an atlas commissioned by the Norman king Roger III of Sicily by Al-Idrisi, a Muslim geographer. Though it was one of the most detailed and accurate world maps of its time, it is very different from our standard world maps in 2025, almost 900 years later. Having plotted parts of Benjamin of Tudela’s journeys on both the Tabula Rogeriana and a modern map, there are several significant comparisons to be made between the two experiences. It is of course much easier to plot many accurate points on a modern map using modern software; GPS systems do most of the work for us once we enter the name of a town or city. I was able to plot dozens of places that Benjamin of Tudela stopped fairly quickly in Google Maps, as long as the location still existed or I was able to estimate where it is now.

On the Tabula Rogeriana, the cities are marked and labeled, but since it is written in Arabic and the points are quite small, I was not able to mark the locations as precisely as on a modern map and instead had to estimate where to place the icons. In addition, the axis is switched, with South on top according to medieval Muslim theology. Many features of the map are misshapen and features are also missing, which made some places difficult to map. Rome, especially, was hard to figure out, because its shape in the Tabula Rogeriana is very different from our modern visualizations.

One of the reasons that the Tabula Rogeriana is laid out very differently is that it places Mecca at the center of the world, which, like the South-North layout was standard for medieval Muslim maps. All of the medieval maps that we have studied, across various religions and regions, are based on ideology as well as, or more so than, geographical accuracy. This shaped the way that medieval travelers would have perceived the world, as well, when religion was central to life and philosophy across Europe and the Middle East, where Benjamin traveled. Modern maps, in contrast, are utilitarian, based on standardized measurements of distance. Though there are various projections which change the size of the continents in relation to each other, they are not constructed to promote a certain worldview or belief system.

In the 12th century, travel was hard and dangerous, and most normal people did not spend very much time traveling through their lifetimes. Travel itself was an enormous undertaking. Now, travel is easy, fast, and widely accessible. In some ways this is reflected in the difference between the two maps. When broad travel was difficult and rare, limited to walking, riding, or ships, constructing a map that accurately reflected the world was nearly impossible. It took Al-Idrisi more than 15 years to complete the Tabula Rogeriana, and he relied mostly on older writings and accounts of contemporary travelers. Modern technology allows us to map the world perfectly and access information about any place in the world in an instant. I was able to be more comprehensive and precise while reconstructing Benjamin of Tudela’s route in Google Maps, but the Tabula Rogeriana is likely closer to his conception of the world and how he would have mapped his travels.

StoryMap page: