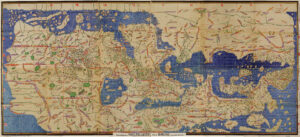

The Tabula Rogeriana was not a one to one accurate map, but considering it is a Muslim map it was ideal for plotting Ibn Battutah’s journey. Mecca was at roughly the center of this map as the most important city to the religion of Islam and the original goal Ibn Battutah had when leaving his home of Morocco for the first time. Besides the geography of the time being somewhat inaccurate, this map gets the general shape of landmasses correct. This made mapping the locations easier than most medieval maps and also makes it easier to read coherently, as long as the reader knows which way it is oriented. Once again because of the Islamic craftsmanship, this map is oriented with south at the top and north on the bottom. East and west are also flipped accordingly, which can cause some difficulty with locating things. The scope is also perfect for tracking Ibn Battutah, as his entire journey never leaves the bounds of this map. Morocco is far on the right hand side and the farthest east he goes is Peking in China, all of which is present there. For its time, the Tabula Rogeriana was considered a world map since the Americas had not been discovered yet. Some known land was omitted from this map of the world, namely the southern two-thirds of Africa. The map was centered around not just Mecca it seems but the entire Islamic world, as at the time the majority of this land was under Muslim control. Seeing as the only parts of Africa that made it in were the northern countries that were primarily Muslim, the continent was likely cut out pertaining to relevance for those that might be reading the map, as well as the cartographer’s own desires.

Ibn Battutah probably did not use maps much at all during his time travelling, mainly due to ease of access. It was also fairly easy to hire guides or rely on slaves that could speak the language of the foreign country they were navigating. Muslims at this time also relied little on written documents and more on memory, with Ibn Battutah’s entire travels even being recorded by his later recounts of them. If he did have some form of map, it was likely lost or stolen as happened to many belongings he travelled with over the years. Aside from the likelihood of him carrying a map, Ibn Battutah would have agreed with the way the Tabula Rogeriana shows the world. Being a jurist of his faith, Ibn Battutah’s whole journey revolved completely around his religion and how it should be practiced. His constant policing of his religion throughout the lands he travels falls in line with the Muslim centric view of the world seen in the Tabula Rogeriana. Mecca’s centrality would also likely please him, as the pilgrimage was so important to Ibn Battutah that he did it more than once in his lifetime. With Islam being such a big part of his life and in some ways his purpose, having the world displayed as it is in the Tabula Rogeriana would be validating to say the least.

As a jurist, Ibn Battutah saw the world in relation to the laws of Islam and its practice. His pilgrimage was the original intention of his journey, but after reaching Mecca he traveled farther to spread his faith and act as an advisor to foreign rulers. In the modern day, it is generally frowned upon to travel somewhere and critique local customs or be judgmental of cultural and religious differences. While it may have been his job, Ibn Battutah judges cultural differences often, sometimes openly to whatever government official is in front of him. Not only would the more cautious and respectful mindset modern travelers have be lost on him, but Ibn Battutah would likely find it difficult wanting to travel anywhere as the Muslim world is significantly smaller than when he was alive. Given the larger reach of Islam, he also encountered many Muslims wherever he went and was met with primarily Muslim countries and cities. Traveling today, he would not be received with Muslim hospitality in every city and not be given such special treatment either, resulting in miserable conditions for travel in terms of what he thought of as standard.

So considering Ibn Battutah’s journey in relation to not only the Tabula Rogeriana but also modern day maps, it appears that the medieval map would be preferrable for him. Not only would it be better in line with his beliefs, but the differences in the modern world make it hard to imagine Ibn Battutah traveling in it or using modern maps.