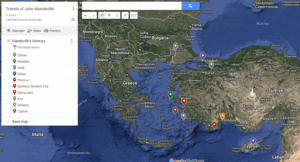

Plotting Benjamin of Tudela’s route onto the Tabula Rogeriana made the differences between medieval and modern maps feel much more obvious than they did in theory. Once the points were actually sitting on al-Idrīsī’s map, I could see how each map carries its own ideas about what matters in the world. The modern map treats distance and navigation as the main concern, while the medieval map treats relationships, routes, and cultural density as the things that make geography meaningful.

Working first with the modern map pushed me into a very standardized way of thinking. I had to turn Benjamin’s “a day’s journey,” “five parasangs,” or “the road is dangerous because of serpents and scorpions” into something a contemporary viewer could recognize. That meant looking for distances, estimating travel time, and describing terrain as if those details were meant to be objective. The modern map doesn’t care that Babylon has biblical ruins or that Hillah has four synagogues and 10,000 Jews. It only cares where those cities sit on a coordinate grid. It has no way of portraying anything more complex than that.

The Tabula Rogeriana, on the other hand, treats space as something lived, which is what makes it perfect for this narrative. The south-up orientation shifts gravity toward Africa and the Mediterranean instead of Europe. That orientation lines up seamlessly with Benjamin’s own priorities. He spends more time in the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt than in Western Europe, and those regions sit at the top of al-Idrīsī’s map. The map reinforces the idea that this part of the world is central. It does not flatten it or minimize it in the way a modern map would.

The climate zones create another layer of meaning and intrigue. Al-Idrīsī divides the world into seven horizontal bands that each carry environmental and social implications. When I placed Benjamin’s journey points into those bands, his descriptions made more sense. His comments on prosperity, strong water systems, and thriving trade fall in the temperate zones. His mentions of instability or sparse settlement fall in harsher ones. The modern map ignores this logic. It gives terrain but doesn’t try to explain why different climate regions feel different to the traveler. The Tabula offers that context immediately, making Benjamin’s descriptions feel rooted rather than vague.

Medieval travelers also thought about distance differently than we do now, and plotting Benjamin’s route onto the Tabula brought that into focus. His sense of movement is tied to people, customs, and the reputations of regions rather than to mileage. A “day’s journey” only makes sense inside a world where travel time depends on terrain, safety, hospitality, and political stability. The Tabula supports that mindset because it organizes space around lived experience. Its climate bands, regional clusters, and emphasis on navigable water routes give a traveler information that a modern map treats as irrelevant.

The density of coastal cities and river routes on the Tabula Rogeriana stood out as soon as I began placing points. The map shows the Mediterranean as a complex, connected system rather than just a boundary. Once I plotted Benjamin’s stops, that network lined up naturally. His itinerary mirrors the patterns the map highlights: ports, commercial cities, political centers, and river crossings. A modern map hides this structure because it treats every coordinate as equal. Without additional notes, it makes Hillah, Babylon, and Kufa look isolated instead of part of a dense, interdependent region. The Tabula makes the social logic of his route visible.

Part of what enables this clarity is the way the map makes its priorities explicit. Medieval maps were not trying to depict the world “accurately” in the modern sense. They were arguing for the importance of certain regions and routes. The south-up orientation, the expanded Mediterranean basin, and the dense labeling of port cities all show where al-Idrīsī believed the world’s energy was concentrated. A modern map distributes space evenly, which washes out these differences. The Tabula shows that some regions mattered more than others, and that acknowledgment helps Benjamin’s journey fall into place rather than float between isolated points.

Scale shifts are part of this worldview. Modern maps stretch space evenly, so long stretches look empty. The Tabula compresses and expands regions depending on cultural significance. When I placed Benjamin’s points, the areas he focuses on felt larger or more central because the map expects those places to matter. It isn’t a distortion; it’s a perspective. Seeing the two visualizations side by side made it clear that Benjamin’s itinerary fits more naturally inside al-Idrīsī’s system than inside a modern one.

Actually plotting the points exposed how much interpretation the assignment required. Some sites, like Babylon or Kufa, aligned easily with the river systems the Tabula emphasizes. Others—especially smaller villages or religious landmarks—had to be placed by reading the logic of the surrounding map rather than looking for a one-to-one match. That felt truer to how medieval maps functioned: as guides blending geography, memory, and narrative. My choices—where to put Kotsonath, how far to place Hillah from Babylon, how to position Ain Siptha—mirrored the judgment a traveler like Benjamin would have relied on. Working this way made the medieval world feel less abstract and showed how geography, storytelling, and lived experience were linked.

While the modern map argues for objectivity and measurement, the medieval one argues for networks, climates, and centers of life. Putting Benjamin’s journey onto both made the assumptions behind each style visible in a way they weren’t before. It changed how I see his travels and how I think about the act of mapping in a broader sense.