Comparing Margery Kempe’s journey on a modern map and the Psalter World Map juxtaposes how a modern traveler and a medieval traveler visualize the world differently.

The modern map provides a modern traveler with a physical and geopolitical understanding of the world. This map defines countries with strict borders, establishing that different regions have separate cultural and political identities. Cities are labeled, with the more prominent and larger cities labelled in bigger fonts, reflecting their social significance and popularity. Generally, continents are scaled to reflect their comparative sizes. While this map is a world map, it also reflects the U.S. government’s (and some Americans’ perspective of the world). For example, this map uses the label “Gulf of America” rather than “Gulf of Mexico.” In addition, the labels are in English, meaning that location names are anglified, and not necessarily written how a native speaker would write them..

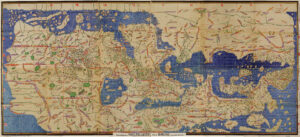

The Psalter World Map provides a medieval traveler with a different physical and geopolitical understanding of the world that is largely rooted in Catholicism. Jerusalem, the holiest city, is placed in the center of the world. The cardinal directions are rotated ninety degrees, with east as north, due to the belief that Paradise (the most Northern/upwards point) was in the same direction the sun rises.

While the modern map is divided into countries, the Psalter World Map has no country borders. The T-O structure of the map uses the Mediterranean Sea to generally separate the world into three land masses, though there are no defined countries with names. Instead, it depicts some prominent geographical features, such as bodies of water and mountains, and prominent cities (represented by gold triangles). This layout of the map suggests a worldview in which different geographical groups of people are viewed not by country, but through a religious lens. Each of the three land masses is representative of the descendants of one of the three sons of Noah, informing how the people in each of those areas may have been perceived. For example, the top left of the map is an illustration of Alexander’s Wall, behind which were meant to be the cannibalistic descendants of the evil sons of Cain, the Gog and Magog. By depicting this religious lore, the Psalter World Map identifies those living in the Northeast of the world as evil cannibals.

Like the modern map reflects a modern day American perspective, this map reflects an English perspective from (roughly) the thirteenth century, due to the location and time of its creation. This English perspective of the world is evident in the amount of locations labelled in each area. Outside of Jerusalem with its many labelled (religiously informed) locations, the bottom left quadrant, closest to Britain, contains the most labelled cities. Meanwhile, the right side of the map contains depictions of the “monstrous” races, or people/creatures with multiple or missing body parts. This portrayal of people in the southern part of the world reflects that those in Britain knew less about the world the further it was from them, allowing speculation and folklore to shape their understanding.

An additional element of the modern map that the Psalter World Map lacks is the inclusion of roads. This aspect of the modern map emphasizes that its priority is to give instruction for travel. The modern map suggests that the modern traveler views their place in the world as a specific geographical point, and the purpose of a map is to accurately assess this point in relation to the rest of the world. It offers physical guidance on how to reach a specific location, not only through its depictions of roads, but its depictions of mountainous terrain and bodies of water, which both accurately reflect the physical world and illustrate potential geographic barriers to a modern traveler. Country borders also provide this type of logistical information, as a border crossing can be an obstacle for travelers.

Instead of providing practical and logistical information for travel, the Psalter World Map’s visual priorities are in religious illustration. This purpose can be seen in the colorful and detailed artwork not only on the map but surrounding the map– angels surround the world, along with the upper body of Christ, who has a large halo of gold. In his hand, Christ holds a T-O sphere, expressing that he is ruler of the world. Margery begins her journey in Britain, located at the bottom of this map, and in moving physically upwards on this map to reach Jerusalem, the map shows Margery is moving closer to God on her journey. This idea suggests that in going on her pilgrimage to Jerusalem, a medieval traveler like Margery would have held the perspective that she was not only symbolically and spiritually growing closer to God, but also physically moving closer to him. Further, by physically (in her mind) moving up in the world, she could have felt that her religious status and quality of life was also moving upwards. By looking at the modern map, a modern traveller can see the impressive length and physically difficult journey Margery went on (traveling more than 3,000 miles southeast), which, though it does not support this religious narrative of moving upwards and closer to God, does reflect the strength of her religious devotion.

While the modern map is a physical representation of the earth, visualizing logistical and terrain-related information, it also reflects a modern day geopolitical understanding of the world. The Psalter World Map frames the world from a religious viewpoint, both physically and through the religious illustrations surrounding it. Rather than categorizing people by countries, it expresses a medieval idea in which areas are generally understood through religious scripture and speculation. In mapping Margery Kempe’s journey on both of these maps, a viewer is able to compare their modern day understanding of the world and travel to the Catholic perspective through which pilgrims like Margery Kempe saw the world and understood other people.