Documentaries and Feature Films

May 26, 2016

Over the past several days, we have watched several films about the incidents we are researching, namely Three Mile Island, Hurricane Sandy, and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in 2011. The first of these was a feature film that was released just before the Three Mile Island accident occurred and, eerily, told the story of a nuclear power plant that, due to human error and negligence, nearly melted down and caused a catastrophe. After the accident at TMI, the film was pulled from many theaters due to its striking similarity to real life events. The film seemed not to have an anti-nuclear standpoint but an anti-corporate one. It didn’t go out of its way to depict the science of nuclear technology in a bad light, but every one of the higher-ups in the corporation that ran the power plant was depicted as either corrupt and greedy or just incompetent. I have a feeling that if the film had been made after the TMI incident it would have gone out of its way to portray nuclear technology as a great evil just as it does with big business.

The next films we watched were documentaries about Hurricane Sandy and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. When I first saw them, I found them to be simple fact-presenting documentaries without much in the way of excitement, but entertaining nonetheless. Our class discussions with Professor Bates, however, opened my eyes to how manipulative these types of films can be to the average viewer. Just by analyzing the title sequences alone we could see how music and images were used to create a sense of authority with which the films presented themselves. It was also interesting to see how these same kinds of images and music were used to evoke certain responses from the viewer, such as when ominous music played as Sandy was approaching the New Jersey coast. It just goes to show that even documentaries that seem to be unbiased and present only factual information can actually be used to sway public opinions and perceptions one way or another.

Three Mile Island Experience

May 26, 2016

On Tuesday our group had the privilege to be escorted through the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. We got to see everything from the security measures to the generators to the reactor control room. Most of the technology that is used to control the reactor is analog, as it would have been when the plant was built and when the accident occurred in 1979. The room is full of switches, nobs and buttons but the most striking thing about it is all of the screens on top of the main panel that light up when something goes wrong with in the reactor building. After seeing how complicated it is and how many people it takes to keep things running (3 teams of workers!) it makes what happened at the plant in 1979 completely understandable. To have to figure out exactly what to do with the reactor in a split second while having to deal with so much sensory input and confusing controls must inevitably lead to a disaster. I was also surprised at how much security Exelon had employed at the plant. There were more security guards and they were far more heavily armed than any other security I’ve seen, even at government buildings in Washington, D.C. Another thing about the plant that I wasn’t expecting was just how clean it was. I don’t remember seeing any dirt or oil or grease on the floor nor on the machines. I assume this is for safety purposes. I’m sure the plant has been extra diligent at keeping their facilities in tip top shape since the accident.

While using nuclear fusion to generate power is certainly the cleanest form of energy in terms of its fuel use (i.e. water vapor is the only immediate product of the reaction), I still think there are some caveats involved with it that should be taken into consideration. One of these is the spent fuel and how it is dealt with. The spent uranium fuel rods used to power the reactor are disposed of after they are depleted by being kept in a pool on-site (due to political gridlock relating to their storage). These spent fuel rods do not seem to have the ultra-high level of monitoring and security as the reactor itself is despite the fact that they are still highly radioactive and will remain so for many centuries. We must find a way to securely store them without causing harm to the environment. Burying them in a storage facility dug into Yucca Mountain in Nevada seems to be the best solution at present but the facility remains empty, waiting for its use to be green-lighted by Washington. Unfortunately, this highly dangerous spent fuel is, and most likely will remain, sitting in a pool of water at the same nuclear power plants that claim to be so safe.

A Documentary Discussion

May 26, 2016

Over the past few days, my group and I have visited the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant and have interviewed a number of people varying from professors alive at the time of the incident to leaders of nuclear watchdog groups. These experiences allowed me to have a greater insight into the way people of the United States interact with nuclear disaster. We made sure to ask basic questions inquiring about where they were at the time of the incident as well as more thought-provoking ones about their positions on having a nuclear power plant right in Central Pennsylvania’s backyard. We made sure to keep these interviews private in order to conceal their identities. I will go further into detail about my interview experience when we do our first interview in New Jersey or Japan as I would like to compare/ contrast my experiences across cultural borders (even within the U.S.).

What struck me the most throughout these past few days have been the number, or lack thereof, of minority stories and/or representation in both the nuclear industry as well as the introductory videos our class had today about The Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant. Specifically, in a NOVA special our class watched today on Tōhoku, all of the scientists and journalists were, well, western males that were from either the United States or other western countries such as Great Britian. This does not bother me too much on a usual basis as access to scientific information is often only accessible to those that have the income or social privilige to do so. However, the documentary was made in order to inform the public about a natural disaster that killed over 15,000 Japanese individuals, and yet, none of the scientists, journalists, or spokespeople were of Japanese origin. Even more so, there was only one interview of an elderly Japanese farmer couple that lived significantly farther away from the disaster than other potential interview candidates. Yes, there exists certain limitations that may not be controllable towards choosing interviewees for an American documentary. For instance, Japan and the United States have not necessarily had the best past in terms of diplomatic relations and other politics, and individuals may have been sensitive towards being interviewed after such a devastating series of events, but I am sure there existed at least a single voice that was willing to reach out and share their story. In addition to this, many filmographic techniques were used to make the documentary dramatic and entertaining such as camera angles and music choice.

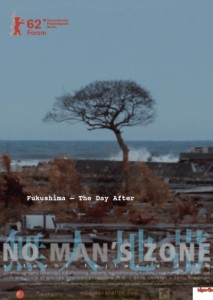

Luckily, the next documentary we watched was entitled, “No Man’s Zone,” which is a documentary done by and for the Japanese people.

This documentary was very raw, and the female narrator incorporated comments that helped the viewer understand the situation at hand. For instance, she mentioned in the beginning of the film that it was difficult for a cameraman to film in a certain area because of the emotional burden attached to stepping on fresh rubble and potentially, a human body. The narrator also incorporated many philosophical comments on the nature of humans. For example, she critiqued society as she stated that people sometimes tend to leave devastating images out of the discussion of the aftermath of disasters because of an innate fear humans have of death. The documentary also consisted of dozens of interviews of Japanese people, both anonymous and not.

Some may see the tactics used in this film as “dramatic,” but I would like to challenge that thought. Is it dramatic because it surpasses the westernized perceptions and expectations we have of documentation, especially concerning natural disasters? Is it dramatic because a woman is the narrator and not a man? Was it dramatic because the images were raw and of rural areas that would not normally have been displayed and represented?

This series of examinations I’ve had can quite literally go on forever, so I would like to conclude on that thought. Perhaps this documentary was not entirely scientific, but it did provide me with an additional lens that I longed for when learning about the Tōhoku region and the Fukushima disaster. Maybe the supreme form of a documentary will contain both diverse narratives and raw imagery as well as information on the scientific processes that occurred during the event, and maybe a clash between the two will never allow us to reach that point.

Blog Post 2 TMI Interviews

May 26, 2016

We interviewed 2 people about the TMI accident while we were in Middletown and 2 while we were at Dickinson College. The first interview was with a daycare worker. This person had children that weren’t her own when the meltdown occurred. Understandably the meltdown of the plant frightened her and she made the decision to leave Middletown and go to her parents house. I was very surprised by the amount of genuine fear in her voice when she talked to us. It must have been extremely nerve racking for her to be in charge of other peoples children during the time. She believed that the NRC was withholding information from the general public, which I tend to agree with. If indeed a big accident were to happen it is no surprise to me that the NRC would try and downplay it. They wouldn’t want the general public to panic, yet it was the withholding of information that made them panic anyways. One of the biggest problem with radiation is that it is invisible. It is hard to understand and react to a danger that no one can see with the naked eye and our interviewee made it clear that this added to her fear. Her commitment and genuine concern for the issue truly showed in the interview. The second person we interviewed was the head of an activist program that focused on working to shut down TMI. He had very strong opinions on the matter and believed the plant would shut down on its own for economical reasons. What I agreed with him on was the fact that nuclear energy should not be privatized and more transparency is necessary for TMI. I thought it was great that his organization monitors radiations on their own and has promised to find other jobs for the people working at TMI. The next person we interviewed was a student at Dickinson College during the meltdown. I thought it was interesting that the campus did not shut down and that students weren’t told to go home. It’s interesting how our interviewee mentioned that most of the students joked about the radiation, but the fear of a hydrogen explosion scared them. Once again the idea of a danger that isn’t visible plays a major role in how many people reacted to the accident. Last we interviewed a physics professor who worked at Dickinson during the time of the explosion. Our interview with this professor was the most surprising to me. The professor mentioned that the radiation leak was nothing to be afraid of and at times this person was even a couple miles away from the plant. From this persons own radiation readings, there were not deadly amounts of radiation leaking from the plant. It was very strange to me how relaxed she was about the incident, and I believe it was due to the knowledge she had on the subject. Knowledge seemed to play a massive role in the entire event and dictated people’s behavior.

Blog Post 1 TMI Tour

May 26, 2016

The first place we studied and visited was Three Mile Island and the meltdown that occurred there in 1979. Being able to actually go on the island was pretty special, and taking a tour of the facility was amazing. One thing that our tour guide stressed was the amount of safety precautions that were in place at the plant today. One thing that was immediately apparent when we stepped onto the island was the amount of security. I couldn’t believe that there is more security staff on the payroll than actual plant workers. Yet, we were able to drive directly onto the island without going through any security at all. This was a strange contradiction because security was extremely tight, but only after someone is already on the island. During the tour I noticed several safety stations and tons of fire extinguishers. There were a couple eye washing stations and even a full shower. All the machinery was  massive and the plant itself was very clean on the inside. I was surprised at how well maintained it was. When we entered the control room I was astonished at all the complicated switches and nobs that were inside. I thought that it was no wonder an accident happened at the plant. The control room was so complex it must take months of training to learn. I was impressed too that our tour guide even said that everyone in the control room has to go through rigorous training. They will work for a couple weeks and then spend another week going through training. I found this process extremely impressive because that is a lot of time spent training for an event that has a low likelihood of happening. It’s even more impressive to think about the fact that the workers jobs are to wait for the worst case scenario and try to prevent it. Also, the supervisor of the control room informed us that the workers at the NRC don’t stay at one plant for long and only a few previously worked at the plant. This is crucial in order for there to be no negligence on the NRC’s part. The last thing I noticed leaving the plant was a chart hanging up outside one of the offices. It was some sort of monetary goal chart displaying what seemed to be the amount of money the plant is making. This was a very sobering image for me to see as we exited the plant because it reminded me that in the end this plant is here to make money. It provides power to thousands, but in the end it is privately owned and meant to make a profit. Overall I enjoyed the tour and it was interesting to hear about the safety regulations in place today there. Read the rest of this entry »

massive and the plant itself was very clean on the inside. I was surprised at how well maintained it was. When we entered the control room I was astonished at all the complicated switches and nobs that were inside. I thought that it was no wonder an accident happened at the plant. The control room was so complex it must take months of training to learn. I was impressed too that our tour guide even said that everyone in the control room has to go through rigorous training. They will work for a couple weeks and then spend another week going through training. I found this process extremely impressive because that is a lot of time spent training for an event that has a low likelihood of happening. It’s even more impressive to think about the fact that the workers jobs are to wait for the worst case scenario and try to prevent it. Also, the supervisor of the control room informed us that the workers at the NRC don’t stay at one plant for long and only a few previously worked at the plant. This is crucial in order for there to be no negligence on the NRC’s part. The last thing I noticed leaving the plant was a chart hanging up outside one of the offices. It was some sort of monetary goal chart displaying what seemed to be the amount of money the plant is making. This was a very sobering image for me to see as we exited the plant because it reminded me that in the end this plant is here to make money. It provides power to thousands, but in the end it is privately owned and meant to make a profit. Overall I enjoyed the tour and it was interesting to hear about the safety regulations in place today there. Read the rest of this entry »

Hello!

May 26, 2016

My name is Connor Moore and I am rising junior and English (soon to be Political Science) major from the great commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As far as my involvement on campus goes, I am the President of Red Devils Sports Network and Co-Sports Editor at the Dickinsonian and next semester I will be leading a service trip. I am also applying to be Student Senate’s Director of Operations next year. I enrolled in this program because of my interest in nuclear technology which stems from my lifelong love of history and study of the arms race of the Cold War. More recently I have also been fascinated in disasters so I felt that this program fit right in with my interests. It is also really amazing to be able to study the Three Mile Island accident, which happened in my (figurative) backyard and that many members of my family still remember. I cannot wait to learn more about TMI and Fukushima as well as the natural disasters that have affected people both in the United States as well as in Japan.

Hello

May 26, 2016

My name is Ian Norden, and I am a sophomore at Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA. I am currently an Education and English double major and am working towards becoming a high school English teacher. Currently, I live in Dublin CA which is about an hour away from San Fransisco though I was born and grew up near New Haven CT. I work in the cafeteria on campus as well as the college cafe called the Biblio. I am applying to be a supervisor for dining services and also applying to an education related community service group known as KDP. The reason I enrolled in this program is because of my interest in emergency management. My father works in this field and I have always wanted to know more about his work. I also am really interested in hearing people’s first hand accounts and stories about these disasters. Their stories give so much more context and meaning to these horrific events. Superstorm Sandy, in particular, is interesting to me because I experienced it in Connecticut and am curious to hear other accounts of the storm. I am obviously most excited about going to Japan and learning about what kind of mitigation the Japanese have for such destructive events.

Hey there!

May 26, 2016

Hello there! My name is Hayat Rasul, and I am from Granada Hills, LA, California. I am a rising sophomore here at Dickinson College. As a first year last semester, I was involved in eXiled Poetry Society, Feminist Collective, Liberty Caps Society, Muslim Student Association, and the Posse Foundation. I am a Mathematics and Earth Sciences double major. Because you really wanted to know, my favorite color is orange and my favorite animal is the snail. Beyond that, I chose to study in this course because of its focus on natural and non-natural disasters and how different communities react to them. Also, as a Californian, quakes and frequent seismic activity have been programmed into my interests as a scientist. I hope to gain knowledge about the differences between the disaster coping cultures within Japan and the United States as well as disaster awareness and preparedness and the way intersectional and diverse identities are involved.

.

Hello world!

May 16, 2016

This is the course blog for the Dickinson College summer mosaic “Meltdowns and Waves: Responding to Disasters in the U.S. and Japan”

Course description:

Disasters arise frequently, but are there ways to identify post-disaster mitigation that over the long term will reduce communities’ vulnerability to disasters? It is this question, in relation to the comparison of Japanese and American societies, which this mosaic proposes to address during the summer of 2016. Through introductory lectures in Carlisle, you will understand the scientific causes of the Tōhoku earthquake, resulting tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident, as well as those behind Hurricane Sandy and the Three Mile Island accident. By means of active community-based learning, especially by interviewing community members, you will understand what the social, economic, and environmental effects of these disasters were on their respective societies.