Nina Simone’s song Mississippi Goddam was written in 1963 after a horrible church bombing in Alabama. Her live performance video was recorded in New York City at Carnegie Hall in 1964. It is now available on YouTube. Her intention with the song was to voice her frustrations with the destructive racial violence that was occurring during the Jim Crow Era. The intended audience was for those who were mourning the loss of the young Black girls who were killed in the church as well as the African American community. Her tone within her performance is filled with anger and force, which amplifies her feelings towards the racist south in the early 1960s. “Mississippi Goddam” connects back to my exhibition since the act of singing about political and racist current events during the rise of the civil rights movement was extremely uncommon for Black female artists to have the bravery to do. She put her career and life on the line by using her platform to shed light upon the plight of marginalized groups in America.

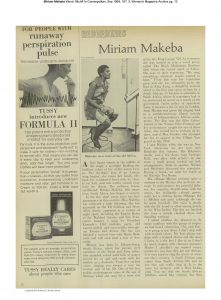

New York’s Cosmopolitan Magazine featured Miriam Makeba. Michele Wood wrote the article within the magazine and Jim Marshall photographed Makeba as she was recording a new song. The magazine was intended for African American audiences and audiences who were influenced by music at the time. The article captured Makeba’s South African attire and revealed her utilization of African sounds within her music. Michele Wood also indicated that Makeba stated that she moved away from professional singing that she learned within chorus training. She preferred a tone that felt more natural and original to her and where she came from. This magazine feature relates to my topic because Makeba’s heavily African influenced artistry influenced African Americans to embrace a culture that is unknown yet so familiar to them all at once. Her style challenged acts of assimilation that were being followed at the time for survival purposes, which encouraged African Americans to rediscover their African roots and decolonize their perceptions of Africa that were being fed to them through mainstream media.

In 1978, Chaka Kahn recorded “I’m Every Woman”, and it became one of the largest selling records in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The song describes the ways in which she embodies a woman of independence, skill, and beauty. The lyrics work to empower African American women despite the attack on Black women since the Reconstruction Era in the United States. Her vibrant vocal range, powerful tone reflect the power that Black women hold in The United States of America. The impact of her music has influenced women like Whitney Houston who recorded a rendition of her song in the 1980s.

Betty Davis’ song “Nasty Gal” released in 1975. She was a funk and rock artist who appealed to audiences that enjoyed that genre of music during the seventies. Her vocal tone was extremely harsh and vulgar. Her lyrics within this song are extremely explicit and sexual. The cover image for this song consists of Davis wearing a Black lingerie dress with fishnet stockings, her legs open, and her mouth open. The openness that she expresses within the image contains a sexual connotation. Her rough vocal tone and her explicit lyrics mirror the ways in which she has inserted herself within a genre that was being promoted as predominantly white and male. The lyrics consist of her attacking the ways in which a man has defamed her character, then reclaiming those terms by describing herself in the same manner. Her song connects to the ways in which she promotes her sexual agency through her platform as a rock and funk artist. The act of inserting herself in a musical genre that was stripped away from Black musicians was radical as well.

Maya Angelou’s poem, “Still I Rise” was written and published in 1978. The poem was dedicated to African Americans, especially African American women. It consisted of words that expressed how the marginalization of Black people will not destroy them. Angelou’s words guaranteed that Black people will continue to exist and rise above any hardships they endure. The repetition of the words “Still I rise” were reassuring and powerful for African Americans. This source is related to the theme of my exhibition because Angelou used her poetry to uplift and embrace African Americans during a time where African Americans felt hopeless due to the lack of progress even after the Civil Rights Movement. It was significant for Black women due to the abuse that they endured from White Americans including the men within their own racial group. Her words within the poem disregarded any forms of marginalization by expressing that nothing will be able to remove her people from existing freely.