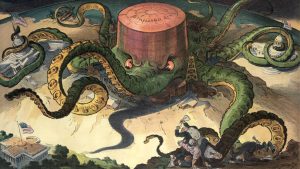

“Next!”

Illustration by Udo Keppler, 1904

This illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House, the only building not yet within reach of the octopus. At this time, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil was one of the biggest and most controversial “big businesses” of the post-Civil War industrial era. As result of highly competitive practices, by the 1880s Standard Oil had merged with or driven out of business most of its competitors and controlled 90% of the oil refining business in the U.S. In addition to this process of horizontal combination, Rockefeller vertically integrated to control every facet of oil production. Standard Oil owned not just refineries, but oil wells, pipelines, retail distribution outlets. Businessmen and politicians challenged the power of Standard Oil in court and legislation, but the firm continued to evolve, survive, and dominate the oil business. Many critics complained that Standard Oil had become too strong and exerted influence on the government itself. This source shows the inequalities between the “haves” and “have nots” during the Gilded Age and how many believed the political system was in danger of becoming corrupt due to the influence of trusts and big corporations.

The Gospel of Wealth

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; … and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer… to produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere trustee and agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.”

This source is an excerpt from Andrew Carnegie’s “The Gospel of Wealth” (1889). An immigrant from Scotland, Andrew Carnegie began his career as a messenger for Western Union Telegraph and a bobbin boy in a textile factory. He gradually worked his way up to the top to become one of the premier industrialists in the United States, owner of Carnegie Steel Company (later to become U.S. Steel when it was sold to J.P. Morgan). In 1889 he published an essay in The North American Review justifying laissez-faire capitalism and asserting the philanthropic responsibilities of industrialists who profit from the unrestricted market economy. Carnegie believes that if the wealth passes through the hands of the few, it can better elevate the conditions of our people rather than distributed in small sums to the people themselves. His idea is that great sums controlled by intelligent people who work for the people, for public purposes, will generate huge benefits for the majority of people and that these funds are more valuable to them than “if scattered among themselves in trifling amounts through the course of many years.”

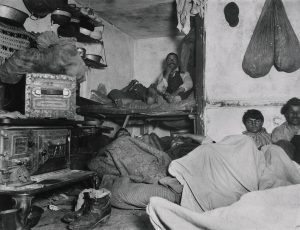

How the Other Half Lives

Lodgers in a Bayard Street Tenement

Jacob Riis was a Danish immigrant who used photography and journalism to show how the less fortunate were living in the United States. In this excerpt, Riis reveals the life of an immigrant living in tenements and how the slums were not talked about and avoided by wealthy Americans. The quotation “one half of the world does not know how the other half lives,” is a theme for this excerpt because many Americans did not want to know the lives of immigrants since it was not directly impacting them and their lifestyle. Riis created this excerpt to uncover the conditions immigrants were living in. This brought the reality of how things were to for some people to light and made it hard for other Americans to avoid it. This source directly relates to my theme of American Wealth Inequalities because it shows the inequality of powerful Americans compared to the less fortunate and new immigrants who have decided to come to America. The influx of immigrants to the United States helped fuel the development of the American economy and brought a tremendous amount of wealth to the country but at what cost? The people who fueled this development and provided the labor to keep it going were getting the lesser end of the deal. This was hiding from the majority of the population but Jacob Riis tried to show the country and enlighten them on what was really going on.

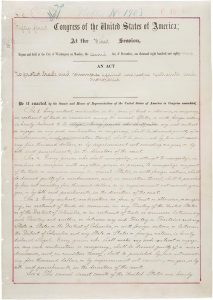

Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890)

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts. It was named for Senator John Sherman of Ohio, who was a chairman of the Senate finance committee and the Secretary of the Treasury under President Hayes. Several states had passed similar laws, but they were limited to intrastate businesses. The Sherman Antitrust Act was based on the constitutional power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. A trust was an arrangement by which stockholders in several companies transferred their shares to a single set of trustees. In exchange, the stockholders received a certificate entitling them to a specified share of the consolidated earnings of the jointly managed companies. The trusts came to dominate a number of financial industries, destroying competition and creating a monopoly. The Sherman Act authorized the Federal Government to institute proceedings against trusts in order to dissolve them. Any combination “in the form of a trust or otherwise that was in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations” was declared illegal. The Sherman Act was designed to restore competition but was loosely worded and failed to define such critical terms as “trust”, “combination”, and “monopoly”.

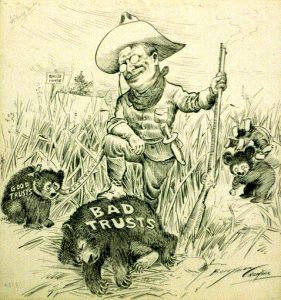

The President’s Dream of a Successful Hunt

The cartoon by Clifford Berryman, shows President Theodore Roosevelt slaying those trusts he considered “bad” for the public interest while restraining those whose business practices he considered “good” for the country. Teddy Roosevelt used the mistrust of the trusts and big business in general to create antitrust and worker protection laws and other federal regulations. However, it is important to note that he did not intend to bring down trusts completely; he wanted the federal government to be able to just regulate them. Roosevelt saw the central government as a tool to prevent power from becoming concentrated in too few people’s hands. He also targeted “bad trusts”, those without a “public conscience”, as targets for breakup, hoping that simply threatening forcible division would scare “good” trusts into being regulated. He started more or less when he took office with the “Square Deal”, which aimed to provide the 3 C’s: Control of corporations, Consumer protection, and Conservation of natural resources.

Looking Backward 2000-1887

“Moreover, the excessive individualism which then prevailed was inconsistent with much public spirit. What little wealth you had seems almost wholly to have been lavished in private luxury. Nowadays, on the contrary, there is no destination of the surplus wealth so popular as the adornment of the city, which all enjoy in equal degree.”

Edward Bellamy’s popular novel, Looking Backward 2000-1887, is frequently cited as one of the most influential books in America between the 1880s and the 1930s. This novel of social reform was published in 1888, a time when Americans were frightened by working class violence and disgusted by the conspicuous consumption of the privileged minority. Bitter strikes occurred as labor unions were just beginning to appear and large trusts dominated the nation’s economy. The author thus employs projections of the year 2000 to put 1887 society under scrutiny. Bellamy presents Americans with portraits of a desirable future and of their present day. He defines his perfect society as the antithesis of his current society. Looking Backward embodies his suspicion of free markets and his admiration for centralized planning and deliberate design.

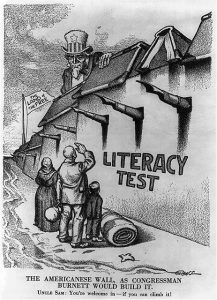

The Americanese Wall – as Congressman Burnett Would Build It

Political cartoon portraying the anti-immigrant sentiments during the 1910’s.

This political cartoon appeared as the nation debated new restrictions on immigration. After 1917, immigrants entering the United States had to pass a literacy test. In the cartoon, the literacy test appears as an impossible barrier to a family of immigrants. Uncle Sam peers out over the barrier, a flag behind him ironically proclaiming “the land of the free.” The Immigration Act of 1917 was the first legislation to dramatically limit immigration into the U.S. It introduced rulings that singled out specific countries and ethnicities, and included conditions that favored privilege over need. The law foreshadowed the 1924 National Origins Act, which ended the years of mass immigration. This source shows how “native” Americans viewed immigrants and immediately regarded them as lower-class. This view could provide insight on why most immigrants that came to the U.S. during this era were already behind most financially and easily fell into poverty.