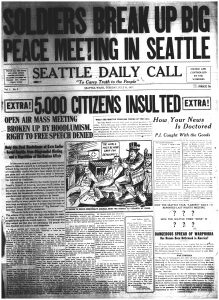

In the early 20th century, new labor newspapers were created at a profound rate. The Seattle Daily Call served as a watchdog on the government’s response to labor-related issues, but this 1917 release served as coverage of the government’s forcible dispersal of anti-war meetings. It includes a powerful political cartoon depicting a man labeled “capital” watching “American Autocrats” gagging the “radical press” and the “labor press”. The heading reads, “in order to bring democracy abroad, we must submit to tyrants at home”. Wartime often serves as a test for the government’s dedication to civil liberties, and World War One was no exception. The government passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts which tightly restricted freedom of speech[1]. The press was especially restrained in its ability to criticize government affairs. Many Americans favored neutrality because of economic ties to Germany, and did not wish to see American lives committed to a struggle they did not deem their own[2]. This source’s purpose is twofold. The event that occurred demonstrates that the government was more dedicated to pursuing its agenda than the protection of the First Amendment. In breaking up a demonstration of free speech and freedom of assembly, the government sent the message that civil liberties were not a priority in wartime. However, the Daily Call’s coverage of the events reminded its readers that the press is a powerful check on the government’s actions when its actions do not align with its values and legal foundation.

[1] Kazin, Michael. 2017. “The Americans Who Opposed The Great War: Who They Were, What They Believed.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 118 (2): 252–55.

[2] Kazin, “The Americans Who Opposed the Great War: Who They Were, What They Believed”, 252-55

Coverage of an antiwar meeting breakup calls the government’s dedication to the first amendment into question.