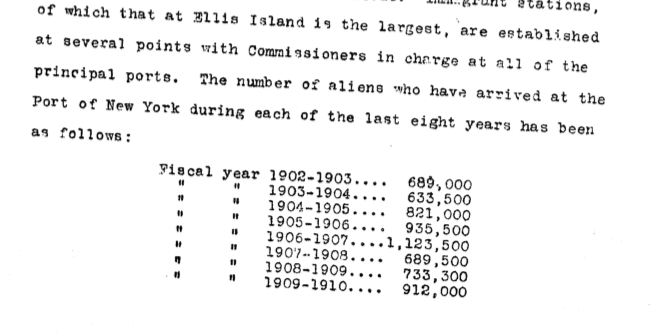

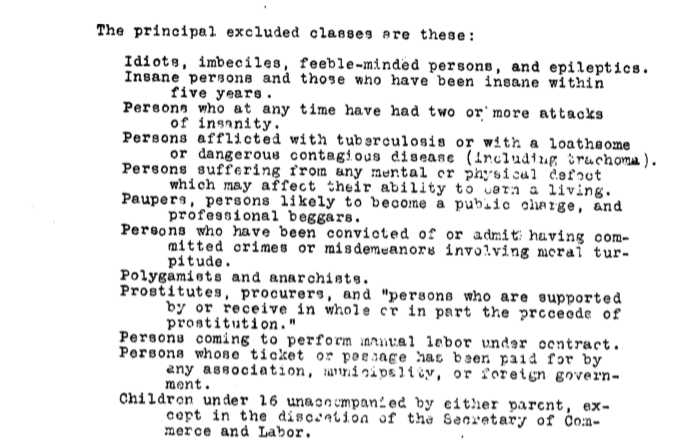

Those items are excerpts of Ellis Island’s organization official document. It gives the number of immigrants who arrived in the US from 1902 to 1910 and delivers the list of the principal classes who are excluded. This source is very interesting because it permits us to understand how the arrival of immigrants worked, what sort of test they had to pass, the huge number of immigrants and their origins. It is also possible to imagine and visualize how Ellis Island was a crowded place during those years. This document offers us a view on how the US did the selection between their future citizens and the others.

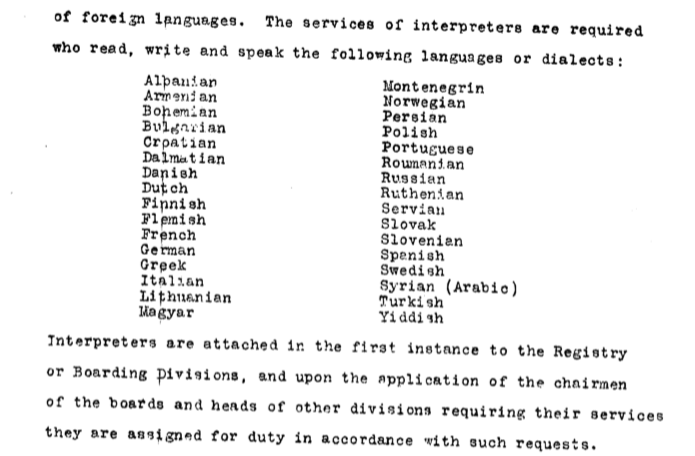

This document is the excerpt of the report of the medical board of the New York hospital, it contains several pieces of information about the New York hospital. The report was created to keep archives about the year 1908. This item focuses on the number of patients and their diseases. The report provides a different point of view of immigration and allows to imagine how difficult it as for everyone to handle the situation in hospitals at this period. This is a good example of how immigration impacts the US economically and socially, especially in a huge city like New-York. Furthermore, knowing the huge number of immigrants that came to the US, this source enables to understand how and why the US government dealt with the situation and the changes that occurred during the early 20th century.

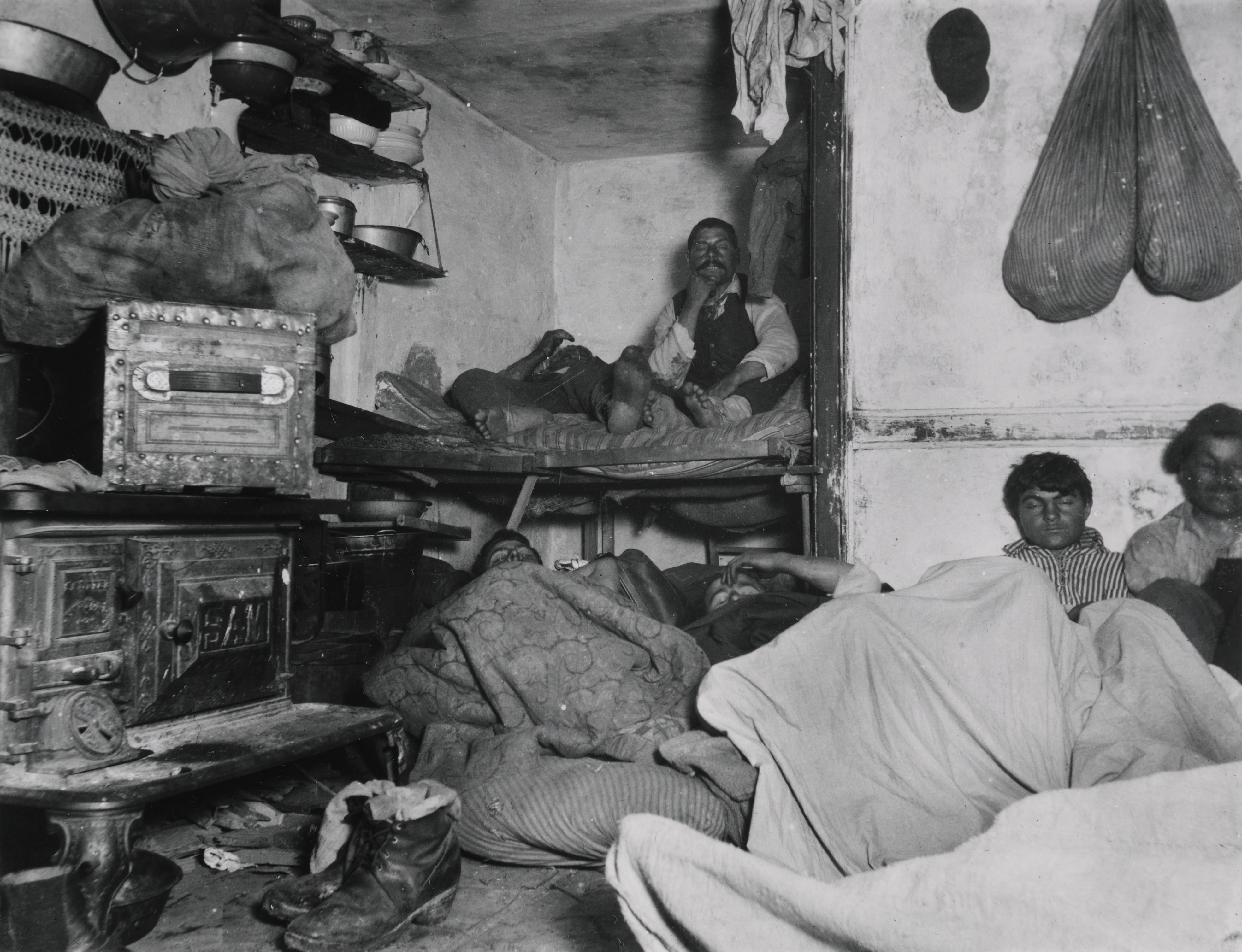

Long ago it was said that “one half of the world does not know how the other half lives.” That was true then. It did not know because it did not care. The half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath, so long as it was able to hold them there and keep its own seat. There came a time when the discomfort and crowding below were so great, and the consequent upheavals so violent, that it was no longer an easy thing to do, and then the upper half fell to inquiring what was the matter. Information on the subject has been accumulating rapidly since, and the whole world has had its hands full answering for its old ignorance.

In New York … the boundary line of the Other Half lies through the tenements. … To-day three-fourths of its people live in the tenements, and the nineteenth century drift of the population to the cities is sending ever-increasing multitudes to crowd them. The fifteen thousand tenant houses that were the despair of the sanitarian in the past generation have swelled into thirty-seven thousand, and more than twelve hundred thousand persons call them home. The one way out he saw–rapid transit to the suburbs–has brought no relief. We know now that there is no way out; that the “system” that was the evil offspring of public neglect and private greed has come to stay, a storm-centre forever of our civilization. Nothing is left but to make the best of a bad bargain.

What the tenements are and how they grow to what they are, we shall see hereafter. The story is dark enough, drawn from the plain public records, to send a chill to any heart. If it shall appear that the sufferings and the sins of the “other half,” and the evil they breed, are but as a just punishment upon the community that gave it no other choice, it will be because that is the truth. The boundary line lies there because, while the forces for good on one side vastly outweigh the bad–it were not well otherwise–in the tenements all the influences make for evil; because they are the hot-beds of the epidemics that carry death to rich and poor alike; the nurseries of pauperism and crime that fill our jails and police courts; that throw off a scum of forty thousand human wrecks to the island asylums and workhouses year by year; that turned out in the last eight years a round half million beggars to prey upon our charities; that maintain a standing army of ten thousand tramps with all that that implies; because, above all, they touch the family life with deadly moral contagion. This is their worst crime, inseparable from the system. That we have to own it the child of our own wrong does not excuse it, even though it gives it claim upon our utmost patience and tenderest charity.

What are you going to do about it? is the question of to-day. It was asked once of our city in taunting defiance by a band of political cutthroats, the legitimate outgrowth of life on the tenement-house level. Law and order found the answer then and prevailed. With our enormously swelling population held in this galling bondage, will that answer always be given? It will depend on how fully the situation that prompted the challenge is grasped. Forty per cent of the distress among the poor, said a recent official report, is due to drunkenness. But the first legislative committee ever appointed to probe this sore went deeper down and uncovered its roots. The “conclusion forced itself upon it that certain conditions and associations of human life and habitation are the prolific parents of corresponding habits and morals,” and it recommended “the prevention of drunkenness by providing for every man a clean and comfortable home. Years after, a sanitary inquiry brought to light the fact that “more than one-half of the tenements with two-thirds of their population were held by owners veto trade the keeping of them a business, generally a speculation. The owner was seeking a certain percentage on his outlay, and that percentage very rarely fell below fifteen per cent., and frequently exceeded thirty. . . . The complaint was universal among the tenants that they were entirely smeared for, and that the only answer to their requests to have the place put in order by repairs and necessary improvements was that they must pay their rent or leave. The agent’s instructions were simple but emphatic: ‘Collect the rent in advance, or, failing, eject the occupants.”‘ Upon such a stock grew this upas-tree. Small wonder the fruit is bitter. The remedy that shall be an effective answer to the coming appeal for justice must proceed from the public conscience. Neither legislation nor charity can cover the ground. The greed of capital that wrought the evil must itself undo it, as far as it can now be undone. Homes must be built for the working masses by those who employ their labor; but tenements must cease to be “good property” in the old, heartless sense. “Philanthropy and five per cent.” is the penance exacted.

If this is true from a purely economic point of view, what then of the outlook front the Christian standpoint? Not long ago a great meeting was held in this city, of all denominations of religious faith, to discuss the question how to lay hold of these teeming masses in the tenements with Christian influences, to which they are now too often strangers. Might not the conference have found in the warning of one Brooklyn builder, who has invested his capital on this plan and made it pay more than a money interest, a hint worth heeding: “How shall the love of God be understood by those who have been nurtured in sight only of the greed of man?”

These sources are a mix of texts and photos also called documentary published in 1890 by Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant. Riis’s work documents and depicts the awful living conditions of immigrants in the tenements of New York by photos and articles. In his work, we can see photos of immigrants; children, women, men who came to a better life in the US but did not fully achieve their goal and are in a situation of extreme poverty. Jacob Riis created this source to denounce the alarming situation, open rich people’s eyes and make them aware of how other people are surviving while they are enjoying the growth of American urbanization. The book is also an artistic way to remember such an important period of US history. I chose this item for several reasons. It shines a light on real immigrants’ lives. The public can’t avoid and is aware of the situation. A work like this can impact the policies and create a movement of help. Jacob Riis’s photos are the perfect example of how to denounce the inequalities that came out of the massive immigration in the US.