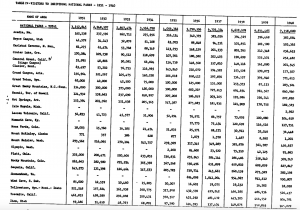

Visitors to Individual National Parks, 1931-1940

This report, released by the Department of Interior in 1941, is a summary of visitors to the national parks from 1931 to 1940. By 1940, there were 26 national parks. The 1930s saw the addition of four national parks: Isle Royale in Michigan, Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, Olympic in Washington, and Shenandoah in Virginia. There is a very significant increase in visitors to the parks during this decade; from 1931 to 1940, attendance to the park more than doubled, with over seven million visitors in 1940 compared to only three million in 1931. The most popular park in 1940 was Shenandoah Valley National Park, despite only being five years old. Great Smoky Mountains was the second most visited park in 1940. There is interesting fluctuation in the chart. For instance, about half of the parks experienced a decline in visitors in 1932, most likely due to the Great Depression, although other parks experienced sharp drops in visitors later in the decade.

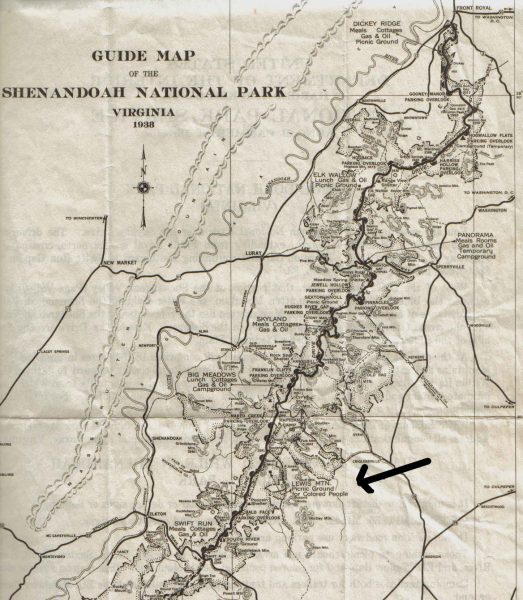

Guide Map of Shenandoah National Park, 1938

There is a history of segregation in the national parks. This is a guide map of Shenandoah National Park from 1938 that marks a specific area for black people. The area noted, Lewis Mountain, was a “Picnic Ground for Colored People.” Shenandoah National Park had segregated facilities until 1950 because state laws applied to the national parks and “separate but equal” was the law in Virginia. The National Park Service justified segregation by saying that only the facilities, and not the parks themselves, were segregated (Young 2009, 655). According to a report titled Administrative History: Shenandoah National Park, 1924-1976, segregation was eliminated in 1950. This history of segregation contributed to a feeling among African Americans of not being welcome at the national parks, something that is still felt today. The visitors to the national parks have always been majority white, middle-class families, and attendance to the parks lacks diversity.

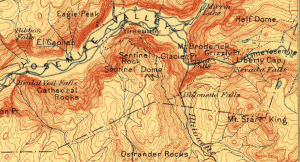

Maps of Yosemite, 1903 and 1956

Yosemite, 1903

Yosemite, 1956

These topographic maps, accessed through the U.S. Geological Survey’s Historical Topographic Map Collection, show the development in Yosemite over a 50-year period. Two famous rock formations are seen on either side of both maps, providing a sense of scale and orientation. El Capitan is on the left middle side of each map, while Half Dome is in the upper right corner. The comparison between these two photos reveals the development that took place in Yosemite in the first half of the 20thcentury. In the map from 1903, there is minimal development in Yosemite Valley. In contrast, the map from 1956 shows the construction of “Yosemite Village” and “Curry Village.” These villages were campgrounds built to provide lodging for visitors and are still open today. In 1956, the NPS recorded 1.1 million visitors to Yosemite (DOI 1966, 11). Attendance records are not available for 1903, although in 1906, Yosemite received a mere 5,000 visitors (DOI 1941, 7). These maps are significant because they show that even in areas protected from mass development and consumption, humans still influence the land.

Crowd at Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, circa 1950s

In this image, crowds gather to watch Old Faithful erupt, one of the most popular attractions at Yellowstone. Cars crowd the road as everyone focuses their attention on the geyser. This source demonstrates one of the biggest issues with the national parks: the balance between preservation and use. This photograph was taken in the 1950s, but finding this balance is an even greater issue today as the population continues to grow and more people become interested in the national parks. In creating the national parks, the National Park Service has two goals. First, it seeks to protect some of the most unique natural parts of the United States and the species that live within them. Second, the parks are designed to be open to the public, so they can enjoy these unharmed, undeveloped areas. While both admirable goals, together they contradict one another. If land is being preserved for its beauty and importance to the country, then it should be open to the public for their enjoyment and recreation. But there is a limit to how much use the parks can handle. Infrastructure becomes worn, animals’ habitats are damaged, and too many people detracts from the personal, spiritual experiences many have at the parks. If crowds must be limited, who gets to go to the national parks, and who doesn’t? This raises issues of diversity of park-goers. At the same time, limits also need to be placed on visitors to prevent these preserved lands from being harmed (more than they already have) by humans’ influence. While it is unlikely that a perfect solution will be found, it is certain that something needs to change because this balance has been an issue since the parks were founded.