Welcome Home Our Gallant Boys, poster (1918)

This 1918 poster depicts a woman in a white robe, holding up the flags of the major powers who fought in World War I. Famous battles are written in the small white panels on the borders while the poster reads, “Welcome home our gallant boys” in red on the bottom and “Peace Justice Liberty” across the top in gold. Pride for veterans after World War I, as in most wars, was abundant and not restricted to any specific nation. This sense of pride fostered by, in this case, the U.S. stands in stark contrast to our government’s actual response to veterans in the years after World War I. At this point in time, the government failed to sufficiently compensate and employ veterans at promised rates, leading to the Bonus Army march in Washington D.C. in 1932, shown in a latter exhibit. This poster demonstrates the trend of the U.S. government to let down its veterans in rhetoric versus action.

Jobs for Fighters, poster (1919)

This 1919 poster shows a former soldier, known as a “doughboy” in America, walking into the U.S. Employment Service to get himself a job. The full title of the poster is ” Jobs for fighters – If you need a job, if you need a man, inform the official central agency – The service is free The United States Employment Service, Bureau for Returning Soldiers and Sailors.” The transition of U.S. industry from making war-related goods back to its prewar activities in the years following the end of World War I was hard on the economy. Returning veterans found their jobs had gone to civilians or found that their position no longer existed, leaving many unemployed. The government tried to help with the U.S. Employment Service, but campaigns such as this failed to employ veterans at the rates promised by the government. Despite an outpouring of appreciation and admiration for veterans, as shown in the 1918 poster, Welcome home our gallant boys, efforts to employ veterans did not reach the same levels. Funding for the federal Employment Service was very low[1] and at the urging of President Hoover, aid would be dispersed mostly at the state and local levels. The poster also denotes the fact that these benefits were often only given to white veterans and not afforded to black veterans.

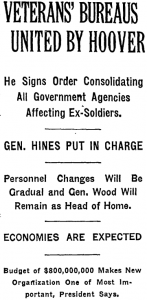

“Veterans’ Bureaus United By Hoover”, Special to the New York Times, July 9, 1930

This 1930 newspaper article describes President Herbert Hoover’s Executive Order 5398. The bill consolidated the Veterans’ Bureau, Bureau of Pensions and the National Home of Disabled Volunteer Soldiers into a federal agency called the Veterans’ Administration, under the purview of Brigadier General Frank Hines. The Veterans’ Administration would be the predecessor of the Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Hoover’s attempt to streamline the process for compensation and medical benefits benefitted hospitals much more than the actual soldiers as laws about delayed compensation for veterans were already on the books. This federalization of the veterans’ benefits only addressed some of the concerns of veterans, least of all the issue of compensation for their service, a hot button issue for veterans in the midst of the Great Depression. The lack of attention to this issue lead to the Bonus Army March in 1932, as depicted in the next exhibit.

“Shacks, put up by the Bonus Army on the Anacostia flats, Washington D.C.”, photo (1932)

This 1932 photograph depicts the burning of the Bonus Army’s camp in Washington D.C., with the U.S. Capitol Building in the distance. The Bonus Army was a group of thousands of veterans, affected by the Great Depression and disillusioned by the government, who marched in Washington D.C. in 1932, demanding their earned compensation for fighting in World War I. In 1924, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, which delayed payments for service to 1945, a date too far in the future for struggling and poor veterans of the Great Depression. Protests broke out the day after a vote to push the date of compensation earlier failed in Congress. While the march was peaceful and the Hooverville in which the marchers camped was orderly, Hoover ordered police and then Army intervention to disperse protesters from Washington and from their campsite on the banks of the Anacostia River. The use of military intervention against veterans was a political disaster for Hoover and contributed to his loss in the 1932 presidential election. This March also propelled the passage of the “Bonus Bill” in 1936, a measure that allowed veterans to immediately cash in the government bond certificates that served as compensation for their service.

Adjusted Compensation Payment Act (1936)

Special to the New York Times. “Bonus Bill Becomes Law; Repassed in Senate, 76-19; Payment Will Be Speeded.” New York Times, Jan 28, 1936, pp. 1.

The Adjusted Compensation Payment Act, against the veto of President Roosevelt, was passed on January 27, 1936. This piece of legislation, nicknamed the “Bonus Bill” got rid of the delayed cash payout of government bonds awarded to veterans of World War I for their service. The Bonus Bill of 1924, officially known as the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, had delayed cash payouts of bond certificates to 1945, when veterans in the midst of the Great Depression were struggling immensely. Roosevelt vetoed the bill originally because he thought it afforded aid to a group of people not based on demonstrated need. Roosevelt saw this not as an issue of veterans’ rights but an issue of fairness. Veterans’ groups and the VA assured Roosevelt they would persuade veterans to not cash their bonds until 1945, like the 1924 act mandated, but many veterans did not wait until then and instead cashed out at the first available date to help themselves and their struggling families. Issues of compensation would be built into the 1944 G.I. Bill, avoiding such issues in the aftermath of World War II.

Notes

[1]Daniel Amsterdam, “Before the Roar: U.S. Unemployment Relief after World War I and the Long History of a Paternalist Welfare Policy.” Journal of American History, Volume 101, Issue 4, 1 March 2015, Pages 1123–1143