“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

On August 18, 2020, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment and on August 26,1920, the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution. It was an extraordinary victory after decades of organizing, activism, and struggle. The first time an amendment for women’s suffrage was introduced in Congress was 1878. The territory of Wyoming was the first to grant women the right to vote in 1890. Other states followed suit, but at the time of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, women could vote in only 15 states.

Despite the broad language of the amendment, ratification did not insure universal suffrage. As Jessica Marie Garcia notes, “the 15th and 19th Amendments were really just saying what states can’t do – they can’t discriminate based on race and gender.” Just as they had after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave Black men the right to vote, states found other ways to discriminate, particularly against Black women and other women of color. Literacy tests, poll taxes, and violence were all used to discourage or prevent some groups from voting.

Although many of us are familiar with some of the (white) leaders of the suffrage movement, like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul, the contributions of women like Ida B. Wells or Mary McLeod Bethune are less well-known. The presence of queer women in the quest for the right to vote has also been made invisible.

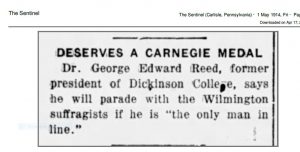

Dickinson has its own stories of the fight for women’s suffrage. In 1911, the Suffrage League of Lloyd Hall was established. In 1912, progressive students formed the Dickinson Equal Suffrage Club. That same year, Dickinson women were seen at a suffrage meeting at the Courthouse wearing “Votes for Women” buttons. The former president of the College, Dr. George Edward Reed, was quoted in 1914 saying that he would parade with the suffragists if he was “the only man in line.” In 1914, President Noble spoke in favor of women’s suffrage at a National Women’s Suffrage Day event hosted by the Equal Suffrage Club. (Thanks to Malinda Triller-Doran and Jody Efron for this information from the archives.)

Dickinson has its own stories of the fight for women’s suffrage. In 1911, the Suffrage League of Lloyd Hall was established. In 1912, progressive students formed the Dickinson Equal Suffrage Club. That same year, Dickinson women were seen at a suffrage meeting at the Courthouse wearing “Votes for Women” buttons. The former president of the College, Dr. George Edward Reed, was quoted in 1914 saying that he would parade with the suffragists if he was “the only man in line.” In 1914, President Noble spoke in favor of women’s suffrage at a National Women’s Suffrage Day event hosted by the Equal Suffrage Club. (Thanks to Malinda Triller-Doran and Jody Efron for this information from the archives.)

Do you want to learn more? Join us at an upcoming Clarke Forum program on Wednesday, September 2 at 7:00 p.m. with Dr. Cathleen Cahill whose talk is called Who Was A Suffragist: A More Diverse View or check out Elaine Weiss’s book The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote or Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, by Martha S. Jones

Written by Dr. Donna M. Bickford, Director, Women’s and Gender Resource Center

August 24, 2020

Note: Cover image is courtesy of the Library of Congress. Inez Milholland Boissevan at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade on March 2, 1913, in DC.