On February 17 at the Clarke Forum, I had the opportunity to hear Anna Lvovsky speak on the history of policing within the queer community. When looking at the history of the LGBTQ+ community, most people’s common perception is that of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 as the spark that lit the fire underneath us to stand up for our identities. We even memorialize these moments by celebrating Pride in June, the same month as the Riots. However, as I have seen for myself within our community, too often we forget that Pride is not just a party or celebration, but a riot against those who wish to condemn us. Lvovsky’s talk insightfully expanded on the heartbreak of discrimination within policing of the queer community that led to the Stonewall Riots, in hopes of reminding us that Pride is still an active fight and our work is never finished.

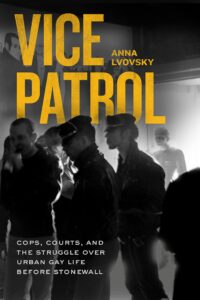

Lvovsky’s new book Vice Patrol: Cops, Courts, and the Struggle Over Urban Gay Life Before Stonewall (2021), was the focal point of her presentation, during which I learned more about the struggles our community faced in the 1950s and onward. One of her most important points was the topic of the “vice squads” made up of “decoys” that were undercover officers meant to entice gay men to solicit sex to arrest them for “disorderly conduct” (as it was illegal at this time to display public forms of homosexuality). Although these individuals are noteworthy by themselves, I want to bring our attention to a specific instance when two undercover officers tried arresting each other, each thinking that the other was a gay man, rather than someone merely pretending to be one. The ethical contradiction is evident here, but what stuck out to me most was the audience’s reaction to such a fact. Everyone, including myself, laughed at the absurdity of it all. Later that night, I thought about the event and wondered why we all laughed at something seemingly so trivial yet full of meaning. After this reflection, I found it profound that this experience did not deter the police from rethinking their techniques on how to arrest suspected homosexuals by this blatant flaw in their system. I was surprised, too, that this moment did not appeal to the officers’ humanity of being arrested solely based on their sexual identity. This example of what seems to be simply an absurd situation could have been a moment of peace within the queer community if only empathy had been the outcome and not fear.

Throughout her talk, Lvovksy explained that the reason the police and federal government were cracking down so hard on homosexuals, specifically gay men, was because they feared they posed a security risk. Specifically, the presumption was that to have gay federal workers meant they could easily be blackmailed by Soviet Russia at the height of the Cold War. Once again, we see the inherent flaw within the system that the only reason why there was a perceived security risk is because of the embedded homophobia and transphobia within the government, which in turn forces the queer community to be closeted in fear of arrest or expulsion. This discrimination towards our community runs deep within our society as is evident from Lvovsky’s talk. Due to this systematic oppression, one might see a pessimistic outlook understanding the work that still needs to be done, but one good thing did come out of targeting the gay community: the formation of that very community.

The ways that vice squads and the police studied and policed the gay community inadvertently created what feminist theorists call “conditions of emergence.” In these situations, by targeting a specific community the pursuers create or validate identity for it to be worth pursuing. The police made textbooks to better understand the “gay world” that discussed fashions for gay men and special codes that would give clues to imply they were gay. Some of these books even had photographic evidence of these “signals” or codes. In a way, the police unintentionally created history books and guides for the queer community and, thus, validated our existence (albeit with nefarious intent). I am not justifying or even defending the actions the police and the federal government took to condemn and harm our community, but it is important to note the power in which identifying has. Ultimately, Lvovsky’s talk addressed some of the history many queer people might not know by reminding us that Pride is a riot. Pride is part of an ongoing battle for our right to be seen as human beings.

Written by Grace MacDougall ’24, Office of LGBTQ Services Pride Coordinator

February 21, 2022