Month: February 2015 (Page 1 of 2)

When I reflect on what’s missing from a lot of games these days, my first thought is “a cure for my crippling loneliness.” My second thought? A sense of discovery and mystery, of finding and uncovering of my own accord pieces of a game’s lore and world. I like going into a world that feels real, one that feels like it wasn’t created with my satisfaction in mind, but rather could have organically existed without my participation. A game shouldn’t have to spell everything out for me, because its job shouldn’t be to please the player. Not all games have to be fun. Games can be more than just things to do in order to pass the time; they can be challenging, emotionally engaging, thought provoking, and even sad. Not every game needs to make me excited, it just needs to succeed in its own right in whatever it sets out to do. Help from the game or being given a sense of power is nice sometimes, but I usually don’t want a game to hold my hand. Why do some games assume I wouldn’t be able to find my own face without a big glowing waypoint?

Two recent games come to mind that have really left a lasting impact on me because of their worlds and infrastructure: Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor (developed by Monolith Productions) and Dark Souls (developed by From Software). I’m not trying to make the claim that these two are the only recent games to have intrigued me lately or that other games are complete failures, but rather that these are merely two examples of the kind of successful world building that I’m talking about. These two games have their own ecosystems of sorts and allow the player to (for the most part) uncover their respective worlds’ mysteries on his or her own.

Shadow of Mordor takes place in Tolkien’s Middle Earth and follows Talion, a ranger from Gondor who seeks revenge upon Sauron’s henchmen for the death of his wife and son. The actual narrative of the story mode is pretty dry and really doesn’t feel all that original. Too often Shadow of Mordor seems like it’s trying to compete with the rest of the Lord of the Rings mythos by imitating other works within the Lord of the Rings universe, namely the Peter Jackson films. Its “me too” attitude makes it look like a little kid trying to wear his dad’s suit; it’s kind of cute at first, but when it tries to drive to work and do your taxes, the act starts to feel a little forced. Its many attempts at shoe-horning Gollum into the plot come off as contrived and Celebrimbor’s endless movie quotes can get a bit tiring, making the story missions in general feel a bit lacking.

However, the game more than makes up for these shortcomings with its Nemesis system, which produces an ever-changing hierarchy of Uruk warchiefs and commanders. The game tracks the rank and combat strength of each of Sauron’s Uruk captains and allows the player to aid, defeat, or enslave any of these captains in their struggles for power. When the player is defeated by one of these captains, that captain will then increase in strength and taunt the player for his failure if he or she chooses to go back for a second attempt at his life. The game will also track the deaths of your friends, allowing you to take vengeance upon the Uruk captain that killed your poor buddy. Lastly, Uruks shift their power positions even without the input of the player, making this system of power feel real and organic. This system is introduced to the player through the main storyline, but for the most part Talion’s interactions with the Uruk captains and bodyguards are not necessary for the completion of the game–which is odd because this aspect is by far the most interesting part of the game.

This ever-shifting ecosystem of war and succession is smart and refreshing and breathes life into an otherwise dull romp through Middle Earth. The game’s world and lore also come out far more clearly in the numerous collectibles that the player can optionally pick up all over the game map. Each collectible is embedded with some sort of memory or engraving, allowing a glimpse into the mind of the individual who owned said collectible. For example, Torvin the dwarf hunter is relatively uninteresting and one-sided in the main story; however, through a few pieces of collectible intel we learn about his relationship with his brother and the reasons for his passion to hunt the Legendary Graug. These pieces of intelligence and history provide context to the action and give the player a glimpse of the micro-level workings of Mordor, something that enhances the overall experience of the game world.

Even though Shadow of Mordor succeeds in terms of its Nemesis system and enlightening collectibles, in some places it still feels like it’s trying to hold the player’s hand. Once the player gets to an area’s watchtower, every collectible and objective is revealed on the game’s map, eliminating the player’s need to seek out secrets for himself. Instead of letting the player seduce and woo the game into revealing its secrets, Shadow of Mordor just drops its pants and flaunts its goods at the drop of a hat. While some may ask why I’m not more critical of its transparency, it’s because I’m just happy that Shadow of Mordor came to the party with pants on at all (I’m looking at you, Pokémon games; I can indeed chew my own food, contrary to how you treat me).

Unlike Shadow of Mordor, Dark Souls is engrossing and intelligent the whole way through. Along with its predecessor, Demon’s Souls, and its sequel, Dark Souls II, Dark Souls has entered the gaming canon as one of the most punishing and cutthroat games in recent years. Compared to some other modern games that treat the player like an idiot and the player’s character like a demigod, the world of Dark Souls seems intent on kicking the player’s undead keister back to 1988. Granted, it ‘s hard, but Dark Souls is perhaps characterized too often solely in terms of its difficulty; there are far more interesting things to say about the game than “it’s harder than grandma’s month old fruitcake.” For one, Dark Souls gives the player a great deal of control over almost every aspect of the game, including the unfolding of the plot. The player controls a chosen undead in his mission to traverse Lordran and defeat the hollowed husk of Lord Gwyn, the world’s previous ‘caretaker,’ if you will. If that sounds vague, that’s because it is vague; the story of Dark Souls isn’t expressly given to the player aside from a few scarce cutscenes. All other bits of story have to be gleaned from NPC’s, from item descriptions, or from observation of the world’s topography and architecture. The item descriptions in particular give poignant clues to the nature of some of the game’s bosses and lore, while NPC’s breathe life into the world and hint at a vastness to the lands of Dark Souls.

Not only does Dark Souls leave its story ambiguous, but it leaves its gameplay elements and explorable world a mystery as well. Once you leave the Undead Asylum and its tutorial scenarios behind, the world of Dark Souls is left up to the player to explore (and probably perish in). Failure and character death are staples of gameplay, but they’re not meant to be deterrents; rather, they’re motivational learning experiences–and death in this game acts as a teaching tool. Dark Souls is meant to be taken meticulously and patiently. Rashness and high stakes are often met with death and loss of time and resources. Combat is like a morbid kind of dance where if you miss a step someone stabs you and steals your wallet (after which you get up, dust yourself off, and go back to get your wallet, but this time you’ve brought Mr. Zweihander and he’s out for blood). In addition to the regular combat, boss fights are an interesting endeavor as well. Bosses are scary and do big-boy damage, but their patterns can often be learned and exploited, and often times the most apparently formidable bosses have the biggest, albeit generally secret or hard to find, weaknesses (in the case of the Stray Demon, you can get him stuck on a pillar, rendering him harmless and easily killable).

The combat system has a lot in common with the missions and objective structure of the game. Which is to say that there really is no overtly easy or straightforward way of moving through the game, but the clever player can find shiny new items and areas and will make it much farther than the impatient player. Though there are mandatory objectives that must be completed in order to finish the game, many can be done in interchangeable order and others can be skipped or ignored. Entire sections of the game can go unnoticed by the player, like the Painted World of Ariamis or Ash Lake, the latter being arguably the most visually striking and beautiful section of the game; it’s reached by exploring a hollowed out tree located in the corner of one of Dark Soul’s main story areas. The Painted World also raises numerous questions about its origins and purpose: Who made it? Why does this place exist? These questions, among others, are never really answered, and I’m okay with that. I want to be able to wonder and make up my own conclusions. I don’t want to be spoon-fed every little bit of information and lore.

I don’t want this piece to be one of those “all modern video games are dumb and for babies” posts, because frankly those kinds of opinions are often uninformed and stuck in the past. Not all games have to be mysterious, complex, or highly intelligent, but I greatly appreciate those that make me forget that I’m playing in a constructed world. Sometimes I just want to get lost somewhere else and experience something new and exciting for myself, as I expect do many other players of video games do. Shadow of Mordor and Dark Souls are both excellent games, and should be celebrated for their success, because for someone who feels a bit jaded these are sometimes a breath of fresh air. In a real world filled with monotony and busy work, games like these let me stretch my imagination a little bit.

It’s not easy to be a feminist and watch TV. I don’t deny there are shows that are making strides in their representation of women and non-normative people, such as Orange is the New Black, Parks and Recreation, Bob’s Burgers, etc. But despite these shows, television seems stuck in a rut. Though there is a lot available, shows stay rigidly within their genre and tend to market towards one single demographic. Cop shows work one way, sitcoms another, teen dramas are different from soap operas, and soap operas are different from prime time. So although the shows employ many different lenses, they remain clustered around a few primary ideas, showing but not embracing diversity in characters or life narratives. Watching through a feminist lens traps you in wanting to praise and encourage a show for the progress it does make but feeling disappointed by the conservative structures that TV can’t seem to let go of.

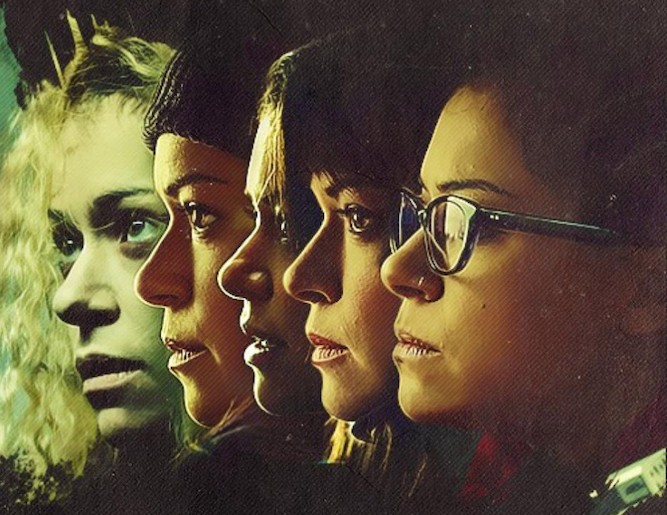

Orphan Black is a show that begins to deconstruct these ideas. For those of you who have not watched it, let me give you a synopsis (unless you want to watch it right now. Don’t worry, I’ll wait). Sarah Manning (played by Tatiana Maslany) is the first and primary character; the audience mostly follows her through the narrative, though in the later episodes this changes. Sarah was raised in the foster system, had an unplanned pregnancy, and ran away leaving her child in the care of her foster mother. The show begins with her return to NYC where her foster mother and daughter live, as well as her foster brother Felix (Jordan Gavaris). Sarah quickly learns that she is a clone, meaning that her DNA was either copied or constructed and that her body is technically owned by the Dyad group. She meets many of her “sisters” (as they call themselves) and joins them in trying to discover their origins. They attempt to sustain their lives while managing the unusual details of their existence and fighting for their autonomy against institutional and scientific control.

Through its story, Orphan Black establishes connections between the personal and the political that most TV shows don’t even attempt–and it does this while managing to maintain a multilayered narrative. Diverse characterizations for women–who are the majority of the cast–and men are central to the show. Unfortunately, Orphan Black is largely lacking in representations of people of color. The fact that a large chuck of the characters are all played by Tatiana Maslany because they’re clones is a contributing factor, but it by no means excuses the show for its white-dominated cast. This was a choice the show’s producers made, so though I praise the leaps that it is making I cannot say it does not have flaws, and I am not defending this significant gap in its representation of the human experience.

That said, Orphan Black creates a diverse representation of the female experience, including sexuality, career, class, religion, ideology, and motherhood status. Through learning about Sarah, her family and the clones–mainly Allison, Cosima, Helena, and Rachel–the audience is shown many different ways in which women live. Allison lives in the suburbs with her husband and two children. Cosima is a queer-identified student studying evolutionary biology. And Helena was raised in a convent and then brainwashed to kill people (pretty unusual, really). The audience is also shown the complex relationships between all of these women, and in particular the generational relationships of Sarah, her foster mother, and her daughter. The connections between women, such as those of motherhood or sisterhood (both biological and emotional), are major themes explored in the show. Strong bonds between women are not the subject of most TV shows at the moment, and it’s incredible to see these realistic and relatable female characters explore their relationships to each other, themselves, and the world. In addition, the show includes interesting male characters. In fact, the male characters are integral to the plot and are characterized just as the female characters are, as having different and complex identities. The show focuses on its female character while consistently bringing in male narratives and identities to complete the complex views of gender that appear in the show.

This diverse picture of identities is continued with the inclusion of queer-identified characters like Felix, Cosima, Delphine (a fellow scientist of Cosima), and Tony. I use the term queer to mean non-normative: anything that is against the traditional structures of society. Felix is Sarah’s gay foster brother who, while male identified, is welcomed into female spaces. He is not only openly gay with an actively queer social life but is defended as Sarah’s brother. His identity is not only outside heteronormative bounds, but his connection to Sarah is non-normative as well, as they are not blood relations.

The relationship between Cosima and Delphine (Evelyne Brochu) is also an amazing accomplishment of the show. After thinking about Cosima kissing her in the episode “Entangled Banks,” Delphine admits “Oh, like… I have never thought about bisexuality. I mean, for myself, you know? But, as a scientist, I know that sexuality, is a… is a… is a spectrum. But you know, social biases they, codified attraction. It’s contrary to the biological facts… you know.” This discussion of sexuality acknowledges both the social meanings and scientific ideas of sexual identity. The development of Cosima and Delphine’s relationship explores questions of identity, how identity changes, and what loving someone means. Tony, while only briefly in the show so far, queers the idea of female experience even more by being a transgender clone. His presence highlights that a female body does not always mean female person. Despite having identical DNA with his clone sisters, Tony identifies as a man and pushes against the gender binary and its limited view of sex.

Not only does the show incorporate all these identities as experiences of life, but it also connects them to political, social, scientific and other external institutions. Through the focus on reproduction and women’s bodies, the show explores how people and bodies are used in science, religion, and politics. The clones are inherently drawn into this tug of war because their bodies are the property of science. This also politicizes the lives of these women’s families. Their status as ‘object,’ not ‘person,’ raises questions about how women’s bodies in particular are commodified, often through their reproduction.

The questions of religion, science, and politics, however, do not end there. The show explores the relationships between these political institutions: where their goals overlap, when they’re in contest, how they view each other, and how their ideologies construct worldviews. This complex look at social institutions in connection with the individual is what makes Orphan Black such a smart and multi-layered show. Orphan Black is not trying to show the audience a single way to live, but is instead asking us to examine how the world around us works and what our place is in it. It shows life not as a contained event, but as connected to and influenced by larger external forces. This is exciting to me, that a popular television show would express such a complex world view.

Orphan Black is by no means the only example of television with diverse identities or political implications. Nor is it perfect, with every identity accounted for, and all voices heard. However, it is a show that attempts to establish the connections between personal and political lives. Its characters show a range of life experiences and identities and build relationships outside of a heteronormative structure. The show stands out against the Normative and promotes a more complex understanding of an individual’s relationship to society. In short, I think it’s worth a watch.

For more Orphan Black information, click here!

Who is the star of Birdman? I ask genuinely, as director Alejandro González Iñárritu, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (fresh off an Oscar win for Gravity), and star Michael Keaton, seem perfectly content to live harmoniously in this wonder of a film, while also threatening to overwhelm each other to stand as the true star. It’s a film about egos though, so I suppose this is only fitting.

Bursting on the scene with the exuberance of youth comes the new Ms. Marvel, superhero extraordinaire. Premiering from Marvel comics in February of 2014 the story starts with sixteen-year-old Muslim Kamala Khan living in a New Jersey where spandex heroes are commonplace celebrities. She spends most of her time writing stories about them. Or hanging out with her friends at the 7/11 EXPY. After sneaking out for a night on the town, Kamala acquires shape-shifting and healing abilities. Now instead of only having to balance her identity as an American teenager with her Pakistani background and her faith, Kamala also has to balance it with new superhero responsibilities. Naming herself in honor of her favorite superhero, the blonde Captain Marvel who can lift cars over her head, Kamala decides to actively help her community, in the same way that the heroes she admired from behind her computer screen do.

Though not the first Muslim superhero in the Marvel universe, Kamala Khan is the first to have her own title. The talented writer G. Willow Wilson, artist Adrian Alphona, and editor Sana Amanat–who comes from a similar background as Kamala–work on the book. This helps create the realistic grounding for what is a fun fantastical premise. With her abilities, Kamala could chose to look like anything, which makes it that much more important that she choses to still look like herself.

When people recommend the new Ms. Marvel they talk about how original the title is. The story of a sheltered Pakistani American superhero with something to prove certainly isn’t one we get everyday. The discussions within the book about trolling, internet fan culture, and what it means to be Muslim in America are all more clearly relevant to the modern age than many other contemporary superhero stories.

However, the ways in which the work really shines are in the combinations of the old world of comic books with these newer socially relevant view-points. Kamala Khan, in fact, has more in common with what came before than is usually admitted. That’s because we genuinely love and want to celebrate this book, and so tend to stress its originality. But the use of familiar tropes should not by itself be seen as automatically problematic. It’s problematic only when these tropes aren’t given the breathing room they need for creativity to shine through. When a hero has to be a certain way because of old genre conventions, a story can end up strangled by its own pathos. And that’s not the case here.

With great power comes great responsibility is the Spider-Man mantra every moviegoer learns. Kamala comes up with her own: good isn’t a thing you are, it’s a thing you do. Her powers are played as a typical coming of age narrative. She’s sixteen and her body starts doing strange things beyond her control. She’s insecure about her looks, only to find herself suddenly able to shape shift. Her parental guardians love her but can’t possibly understand what she’s going through. Spider-Man. The story we’re deja-vu-ing on is Spider-Man.

But Spider-Man gets dated. We’ve seen so many variations of his story where only slight details are changed. At this point, superhero stories with a white dude dealing with his emotions on an explosive metaphoric level are boring. Though there’s some interest in seeing how storytellers pick at these narratives for new material, goodness, by this point it’s a little like beating a dead horse. Story elements start to lose their punch. In the 1960s the idea of a father disapproving of his daughter dating a nerd seemed more reasonable. In the most recent Spider-Man movie, the writers had to incorporate the idea of mental instability to initially explain Captain Stacy’s dislike of Peter Parker. Now Marvel studios has been given the opportunity to reincorporate the character into the cinematic Marvelverse and we’re going to see him struggle for the third time in thirteen years. Even the casual fan has to sigh at the state of the story.

Superman has similar difficulties connecting to an audience in the modern age. The multitude of his powers combined with his strong moral compass makes him a difficult egg to crack for DC Comics. The most recent solution that I’ve enjoyed has again taken him to this place of immaturity. The Spider-Man coming of age narrative is used as a young Clark Kent discovers and struggles to control his new powers in Smallville. Clark Kent sees a pretty lady and his heat vision starts to act up! However, the show begins to struggle as the cast grows older because they are trapped within the confines of this already established narrative. Clark has to become Superman. No matter how a character might grow over the course of a television decade their eventual place in the universe has a set path a writing team doesn’t have the power to change. This transforms characters like Lex Luthor, or hey inevitable Green Goblin Harry Osborn, from tragedies to foregone conclusions.

Ms. Marvel is a good story because it uses cliché superhero origins not as a crutch but as a spinal column on which to attach the meat of characterization. Kamala is carefully created to be relatable without having to veer into bland, to be admirable without being inhuman (though she is in fact an Inhuman). She is new and her supporting characters could be almost anything. Even so, the patterns they present are familiar to our brains. One character is the locked-out-of-the-loop best friend. Another is the beleaguered secret keeper. Kamala is going to struggle with her identity, her place in the world, and her new responsibilities. Presumably she may lose things she cares about and make mistakes. But the fun is not knowing what those mistakes are going to be.

So yeah. Go read it. I dare you.

Just based on the title alone, Jane The Virgin is an attention grabber of a show. This CW comedy-drama focuses on Jane Villanueva, a virgin (surprise, surprise), who finds herself at the center of numerous crazy developments that complicate her life and the lives of those around her at every turn. It was developed for an American audience by Jennie Snyder Urman and is loosely based on a Venezuelan telenovela called Juana La Virgen. The show itself is a pseudo-telenovela and pays a lot of tribute to the genre: its characters are predominantly Latino, dialogue is occasionally in Spanish, and a fictional telenovela regularly plays on the characters’ TV screens.

Jane (Gina Rodriguez) is young Latina woman going to school and waitressing in Miami, where she still lives at home with her flirtatious mother (Andrea Navedo) and devoutly religious ‘Abuelita’ (Ivonne Coll). In the series premiere, Jane finds herself artificially inseminated because of a mix-up at the gynecologist. This plays into the religious undertones of the show as Jane becomes pregnant despite still being a virgin (her purity is something her grandmother preached to her to protect when she was younger). The mis-applied sperm, it turns out, belongs to a man named Rafael (Justin Baldoni), who not only runs the hotel Jane works at but also happens to have been her first kiss five years earlier.

For Jane’s detective-boyfriend Michael (Brett Dier), learning that his virgin girlfriend has become pregnant inevitably puts some serious strain on their relationship. By the end of the premiere, the two decide to take their relationship to the next level by becoming engaged to be married. The symbolism is apparent in the final shot, where Michael knocks a white flower–symbol of Jane’s virginity–out of her hair and they embrace. This foreshadows what is in the imminent future for Jane, although when this moment of deflowering will come is a big mystery.

As with a typical telenovela and soap opera, if you thought this show couldn’t get any more complicated, you would be very wrong. Just to give you a taste of all the storylines in this show, here are some of the things that a viewer will have to follow. Rafael’s sperm (frozen before a bout of cancer left him infertile) had originally been intended for his devious and scheming wife Petra (Yael Grobglas) as a way to salvage their marriage. Despite this ploy, Petra is sleeping with Rafael’s best friend Zaz, who Michael just happens to be spying on because he is the last link to a missing drug dealer. Jane’s absentee father also happens to be the star of her favorite telenovela, but her mother can’t bring herself to tell this to Jane. Oh and the gynecologist who caused this mix-up? None other than Rafael’s sister Luisa, of course.

This complex web of interconnecting stories is both a flaw and one of the appeals of Jane The Virgin. On the one hand, it keeps the speed of the show very fast-paced and there is never a dull scene. The music also plays into this process: a frequent use of background music conveys the sense that a scene is about to reach its climax (pun intended) and then snowball into the next big moment. This gives the show a rhythm that it complicates with every scene. On the other hand, the complex plot leads to there being anywhere from seven to fifteen legitimate and important story lines going on at all times. This can make the show seem scattered and hard to follow on occassion.

The writers do a really good job combating this complex narrative by having every event and person related to one another. Every single scene has larger implications and there is no wasted time in each episode. The writers also utilize a narrator to make sure the audience is keeping up with all the characters and their stories. He has a very jokey and omnipotent voice. He is in on all the jokes and aspects of the show that the audience can see but the characters cannot. Relatively frequent flashbacks also help tie the story together to explain both character motives and relationships between different people. Despite the high amount of turning wheels on the show, the writers are able to tie it all back together, providing a satisfying assurance to viewers that any confusing event will be explained in due time if they continue watching.

The directors of the episodes have a tendency to hint at a lot of things in the future. There is an incredible amount of foreshadowing, and part of the fun as a viewer is to catch the symbolism in what seem like otherwise mundane details. This gives the viewer a privileged view that is way above the characters themselves and can thus draw viewers back to see if their predictions turned out to be correct or if they misinterpreted the hidden message in a scene. The main example of this is the sort of ‘will they, won’t they’ feeling surrounding Jane and Rafael. They have a classic rich vs. poor, Romeo and Juliet dynamic between them. This becomes confounded by the fact that Jane and Michael really do care about each other as well, so it will be interesting to see how this unfolds on the screen.

For all the narrative trickery and complexity, however, it is the characters who are the real driving force behind the show. At first glance, they all may seem very one-dimensional. Their basic personalities, for instance, are established very quickly from the moment they are first on screen, and it seems at first that they are all extremely easy to figure out. However, as the show progresses, all of the characters are shown to have much more going on. And in due time they become much more multifaceted. This is a really crucial part of the show because it complicates a lot of the decisions that characters have to make, since all of them are dealing with internal struggles.

Though the writing helps, the depth and attraction of all the characters is mainly due to the performances of the actors. Rodriguez is really the backbone of the whole cast. She plays all her characters’ emotions to the fullest and is asked to do so across a large spectrum in every episode. She shines brightest in the tougher, dramatic scenes but is still able to hold her own with the comedic scenes. She was deservedly recognized for her abilities when she won the Golden Globe for best actress in a TV comedy this year.

Navedo, who plays her mother, heavily supports Rodriguez’s rollercoaster of highs and lows. Early on, she is presented as a ditzy, young, carefree mother going from man to man. But she is capable of much deeper scenes when she is put in a position to showcase her nurturing side and take care of Jane. The same could be said for Baldoni, who is able to portray the difficulty and complications within his character with just his face and posture when necessary. Additionally Grobglas does a fantastic job keeping the audience guessing as to her motives and what side she is really on, utilizing very emotional performances that can turn on a dime through expert use of a very sly grin. Some of the supporting roles are more caricatures, with the overbearing grandmother, backstabbing best friend, and clueless/self-indulged television star, but they all do a great job holding up the rest of the show and bringing it together.

For what it’s worth, the show is also pretty progressive. The large majority of the central roles are Latino characters, which is somewhat revolutionary for U.S. television today. This is important for the show, because it is an ode to telenovelas and it is showing that Latino actors and characters can lead, carry, and tell a very compelling story to an American audience that is typically drawn to predominantly white shows like Everybody Loves Raymond, The Middle, and Modern Family. However it is interesting to note that while a lot of the characters have accents or Latino names, they are not actually all Latino, and the exact ethnicity of any person on the show cannot be determined. Rodriguez, Navedo, and Coll are all of Puerto Rican descent in real life but the show is situated in Miami, a very Cuban city. Surprisingly enough, given their accents, at times, and appearance, Baldoni and Grobglas are not Latino in the least. Baldoni’s parents were of Jewish and Italian descent, while Groblas grew up in Israel and her parents are from France and Austria (though her ethnicity on the show is even harder to tell than the others). This is a testament to their acting abilities; however, it also brings into question why actual Latino actors were not used for more of the roles, as they are an underrepresented acting group in network television.

Additionally the show deals with a lot of heavier issues in society. Examples of this is whether or not Jane should get an abortion and the decision over when to lose her virginity, in addition to a lesbian relationship with one of the recurring characters. These are topics that other shows might shy away from for fear of controversy and Jane The Virgin should be commended for tackling them head-on.

Ultimately, Jane The Virgin is a delightfully charming show that still possesses the ability to put amazing emotional scenes at its core. This charm makes sense given that it is on a network station and marketed towards a younger audience than more conventional network shows. It is quite action-packed and complex to say the least, yet because of the foreshadowing and narrator, a viewer could miss an episode or two and still have a strong grasp of the majority of what was going on. The whole show also has a very fantastical feel, which a viewer needs to accept given some of the ridiculous things that happen. This magical feel is conveyed through the intertwining stories being told, the music and narrator, and the utilization of very vibrant colors.

It is hard to categorize this show into one genre as it has elements of comedy, romance, drama, and even mystery. It may sound like a lot to comprehend in one show, but Jane The Virgin is quite brilliantly constructed to have everything eventually tie together. This is not a laugh-out-loud show per say, as the humor typical arises from situations of classic misunderstandings that drive the plot forward. The jokes have a playful feel to them, toeing a line between childish and mature so both adolescents and young adults can find it enjoyable. This has been highly recognized among a large variety of people as the show was nominated for a Golden Globe for best TV comedy series this year, despite its airing on a relatively smaller network. Jane The Virgin is a show with such an incredible amount going on that it can be intimidating, but it does a really good job balancing the funny with the heart wrenching, the absurd with the relatable, and even addressing contemporary issues.

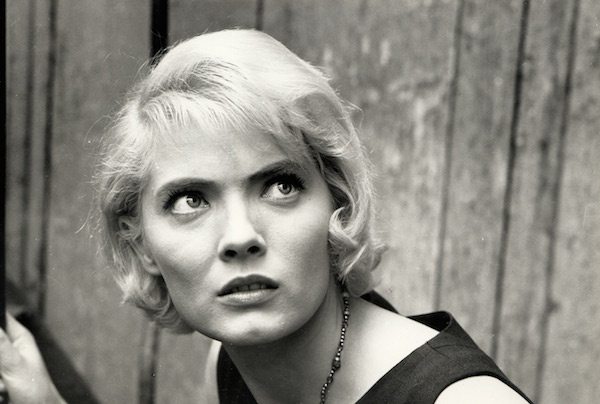

At night, as my head sinks into my pillow, I often wonder if I’d be able to recognize love when it appears in my life. I usually arrive at the conclusion that I have, on countless occasions, obliviously waltzed right past it with a big, dumb grin on my face–and then I start thinking about Agnès Varda’s 1962 film, Clèo from 5 to 7.

There are a handful of terrific films in history that successfully portray action in real time, but none of them quite as precise, as meticulously committed to capturing real human experience, as Cleo from 5 to 7. After watching the film I feel like I’ve just spent 90 minutes marching down the Left Bank of Paris, soaking in the energy of the early sixties alongside our protagonist. Breaking away from conventional film technique, in which narrative rhythm and drama is manufactured through the manipulation of space and time, Varda embraces the subjectivity of her lead, ensuring the viewer experiences every moment the way Clèo (Corrinne Marchand) does, in real time. Every second builds on the last, adding tension, and before the end I’m totally invested in Clèo. Varda masterfully deploys the real-time structure so as to transform a story that, constructed in almost any other way, would feel utterly tedious into a gripping character study. Instead of just a vain, narcissistic, and shallow singer, Clèo changes into a relatable young woman whom we care about immensely. As Clèo learns to recognize love, what’s truly significant or insignificant in her life, we learn to appreciate and love her in return, and walk away reevaluating our own lives.

The plot is concentrated entirely within this 90-minute span of Clèo’s life. In France, the hours of 5 to 7 are considered the hours when lovers meet, but Clèo, a normally carefree young woman, is in dire straits. Clèo is disconsolate, awaiting the results of a medical test that will determine whether or not she has stomach cancer. The slice of her life we experience is the 90 minutes prior to her hospital visit, the moment of truth.

As I’ve mentioned, this is not merely a formalist exercise of cinematic virtuosity. Varda once commented on this film, calling it a “portrait of a woman painted onto a documentary of Paris,” and though I agree with her assessment, I don’t think it communicates the extraordinary elegance with which the film portrays Clèo’s subjectivity. Varda not only captures the material, physical details but also the way Clèo’s mind processes them, the way her personality and mood informs her interactions with and her perception of the world around her. It is this incredible quality that makes Clèo’s behavior, much of which seems initially unremarkable or simply quotidian, so engaging. And I believe that it’s this extremely modern and subtle form of expressionism that has helped the film age so well.

Clèo’s path along the Left Bank is, geographically, straightforward; she stops for some food, goes shopping, takes a cab, stops at her place briefly for a music rehearsal, walks through a park, etc. But emotionally, as she draws nearer and nearer to the moment that may potentially signal the final stage of her life, Clèo undergoes a significant character arc without seeming–just like in real life–to have reached a distinct instant of change.

Clèo from 5 to 7 is a pure representation of life for a young Parisian woman in the early sixties, and because of this it’s easy to crown Varda as standard-bearer for feminist cinema. She herself has rejected this title but, either way, Clèo is ahead of its time. Many critics have recently taken a new stance toward, calling it, for example, a strikingly complex instance of “postfeminism” in cinema.

Of course, for a lead character, Clèo certainly doesn’t seem well equipped to garner sympathy from the viewer, at least not at first. She is immature, shallow, vain, petulant, and, if not for her stunning beauty, would likely alienate most of the people around her. She seems detached from her small but vaguely promising career as a pop singer and she is also privileged–financially supported by her older lover who makes no demands of her. She lives in a nice apartment and can afford numerous luxuries.

Everything about Clèo is potentially repellent, but in the end compassion wins out. Clèo’s plight, and Corrine Marchand’s tremendously sensitive performance are irresistible. Watching Clèo re-evaluate her life, her possessions, and relationships is immensely gratifying, and as she matures she’s able to start confronting her more unsavory characteristics. Few films pull off this type of character transition with such grace.

Some may find it surprising, then, to learn that Agnès Varda was not trained as a filmmaker or film critic, like most directors of the French New Wave, but as a photographer. Her films bear this distinction. Of all the major directors in the French New Wave (Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Louis Malle, Chris Marker, and Jacques Demy–Varda’s husband), Varda seems to produce the work least influenced by the inherent smugness of being a film snob, a particular smugness often required to make a film that changes cinematic history. Though she’s displayed total mastery of cinematic form throughout her career, Varda’s primary concern has always seemed to be the characters. Her formal experiments occur within the boundaries of her narrative structure, and therefore contribute to the complexity and richness of the story. It’s all about Clèo.

That is the source of the connection I feel to Clèo, why I so often recall this film when reflecting on my own life. Clèo, like all of us, has her own concerns, her own fears and desires. Her true struggle throughout the film is learning how to keep these concerns from dominating her, from dictating her behavior and emotions. When she steps back from herself she gains perspective on the world around her, and although she begins to recognize that she’s unhappy, that she’s been oblivious to what’s truly important to her, everything remains okay. She’s also beginning to recognize how many opportunities there are for her to find the happiness and comfort she seeks. She’s learning how to truly interact with and love other people, and it’s amazing to watch.

“Listen carefully to first criticisms made of your work. Note just what it is about your work that critics don’t like–then cultivate it. That’s the only part of your work that’s individual and worth keeping.” – Jean Cocteau

Sara Shahriari is a freelance journalist living in La Paz, Bolivia, and working in the Andean region. She reports on a broad range of topics with an emphasis on social justice, the environment, and politics. Her print work has appeared in The Guardian, Al Jazeera America, The Christian Science Monitor, and Indian Country Today, and her radio work on Deutsche Welle.

BRITTANY: Tell me a little bit about how you got to where you are now.

SARA: Well, it was a circuitous path. I studied writing in college and was always really interested in it, but wasn’t sure how that would play out into a career. I considered going to law school. I considered going back to school for a bunch of different things, and I eventually decided that journalism would be the best way to sort of merge together the things I loved. I always knew that I wanted to work abroad and I decided on Latin America because I had already studied some Spanish, and I felt that I could learn enough Spanish in a not really extended period of time to be able to work well there. I went abroad after college and spent a year teaching English at a university in Ecuador, which is also in the Andes. The Andes start in Columbia and run down through Ecuador, Peru, into Bolivia, and a little bit into Chile. So I loved the mountains and the culture and it’s such a dynamic area in terms of how a lot of forces are interacting, like governments, corporate entities, indigenous identities. It is, to me, an incredibly interesting area.

When I finished teaching in Ecuador, I applied to go to grad school for journalism. I went to the Missouri School of Journalism and got a master’s degree. While I was there, I produced a Spanish language radio show. I studied magazine journalism. I just studied radio a bit, and then I got a grant from the school to go to Bolivia to work on a project for a while.

I came to Bolivia with that support and started working, and it was at a time when a lot of international journalists were actually moving on from Bolivia, so there was just fortuitously an opening for me to pick up some work here. I ended up staying and getting more work, and staying and getting still more work, and just sort of having a chance to really learn while writing, learn through working and writing all the time.

BRITTANY: I’m also interested in journalism and I know I’ve heard mixed things about going to grad school for journalism or even majoring in journalism given the state of the industry today. What are your thoughts on that? Do you think that going to grad school was necessary?

SARA: It was good for me because I hadn’t focused on journalism as an undergraduate. If I had focused on journalism in any way as an undergrad, however, I don’t think a master’s degree in journalism would have been the right move. But for me, it was good to be able to do it. As an undergrad, if you’re already focusing on journalism, I don’t think you need a graduate degree too unless your aim is to acquire very specific new skills, like perfect video reporting, that will place you better in the job market.

BRITTANY: What was your major in undergrad?

SARA: Creative writing and English literature. So I was very writing-oriented but more in the essayist line of things. I was not very good at planning for the future, but at the time it seemed likely that I would end up going to law school. So an undergraduate English degree seemed like a good precursor to that if that’s what I decided to do. Then after working with a law firm for a couple of years as a paralegal, I just decided that law wasn’t right for me. So I reoriented my career direction.

I think you can go to grad school or you can just get a job at a paper and do it. I was fortunate in that I didn’t have to go into much debt for grad school because I TA’d while I was there, and ran this Spanish-language radio program, so actually most of my tuition was waived. I personally would never have gone into a lot of debt to get a master’s degree in journalism because I knew I wasn’t going to make that money back. It’s not like you go to a medical school and you get a zillion dollars into debt and then it’s pretty established that you get a high salary afterwards. In journalism, most of us are not going to make a very high salary. So I thought going into a lot of debt was not a great idea.

BRITTANY: When did you know that you wanted to report on the specific issues you focus on, like the social justice, environmental and political side of things?

SARA: I think that’s just what personally speaks to me and interests me as a reporter. I don’t really like being in a scrum of reporters jockeying to get near the political figure who’s going to comment on the issue of the day. I like to be talking a lot of times with people who have never spoken with the press before, or have very limited contact with the press. I like finding voices that are hard to find and hearing the voices of people who are not often approached to share their experience. That, to me, is important and compelling and gives journalism that intensely human connection that I think is one of the best things about it.

BRITTANY: What do you think is the most rewarding piece that you’ve written?

SARA: A couple of years ago, I did a series of stories on the pollution of Lake Titicaca—that’s on the border between Peru and Bolivia—and those stories together formed what I think is a pretty diverse journalistic look at the issues affecting that area, which is really important environmentally and also home to so many people. So in that situation, I liked that I was able to spend a long time looking at that issue and examining it from different angles.

Also—and maybe there’s not one story on this topic that I think is the best thing that I ever did, but in terms of understanding the topic: the issue of child labor in Bolivia and how children have in some cases organized to defend their right to work as children. Getting to know the issues driving child labor was particularly rewarding because child labor is one of those topics that if you grow up in the States, you’ll hear it like, “That is bad, that is bad. It must be stopped. That factory must be closed. That person must be prevented from working.” And it’s not great, that’s for sure, but if you get to know young people who are working and see the reality of their daily lives, you understand why that work is necessary for their survival, and how diverse the reality of child laborers really is. So my knowledge on that topic and the time that I’ve spent reporting it is probably one of the things I’m most proud of because I think I may have helped people understand the issues behind what’s really a very controversial topic.

BRITTANY: Describe your typical day at work.

SARA: I have a home office. So my typical day is to get up maybe around 7:30, take my dog out, come back and get ready for work. Working from home or working freelance is always a challenge because nobody keeps you on a schedule. So you can sleep until noon if you want—although doing that would not be very good for your work overall. So I try to get up, get dressed, have breakfast and go to the office—even though the office is still in my house. In the morning, I skim all of the headlines from the big national newspapers in Bolivia to keep up-to-date on what’s happening across the country.

I might make phone calls to setup interviews. It sort of depends because freelance writing and writing in general is pretty cyclical, like sometimes you’re in an interview phase, sometimes you’re in a research phase, sometimes you’re in a writing phase, and each of those means different things. In the research phase, I’ll just go to a coffee shop with 300 pages of PDF documents and read and highlight and take notes.

If I’m in the reporting phase, I’m going to be calling people, setting up interviews, maybe traveling to other cities out in the field, getting to know people, talking, listening, recording, and just trying to get all the information that I need. And then of course I take all that information to my office and I just lock myself in the office and try to listen to all my interviews, transcribe sometimes and put together the text. So the day varies depending on which of those phases I’m in.

BRITTANY:With freelancing, do you have connections to certain papers like The Guardian or something, where you have to do a number of pieces for them, like two a month or something like that, or do you just pitch your own ideas?

SARA: I pitch my own ideas usually. It’s extremely fluid and that’s the interesting thing about freelance. It all depends on you to generate and then execute the idea, which can be an exhausting cycle to always be stuck in. But at the same time, it’s amazing because 99% of the time you’re doing what you want to do, not what somebody’s told you to do.

BRITTANY: What’s your tactic? Do you have any strategies for finding new stories and creating new ideas and coming up with new content?

SARA: I think the best thing that you could do if you’re a foreign correspondent is talk with people. I mean, I have a really interesting group of friends and contacts in Bolivia that work on a variety of issues. So we just talk. Talk about my work and listen to other people talk about their work, bounce ideas off people who aren’t necessarily journalists. I mean, it’s all about having your ear to the ground in that way, and staying on top of the national press. Those are the people who are out there following stories every single day. Of course they have to write a different kind of story than you have to write.

You’ve got to stay on top of what’s happening not just in the city that you are in but across the country. So you might be able to identify some national trends. So I think, yeah, just listening and reading are good ways to get your story ideas together.

BRITTANY: My mom is a freelance writer too and she talks about the challenges of working at home and the sleep-until-noon thing, how you can actually do that. I don’t know if I could be disciplined enough to do that.

SARA: It really requires . . . it’s like the best of jobs, the worst of jobs. It offers you such freedom but occasionally it’s like, “If only somebody would just tell me what to do!”

BRITTANY: Right, exactly. So I guess that may be one of the difficulties, but other than that, what do you think are the difficulties for being a freelance writer as opposed to working for a single company?

SARA: I think that when you freelance you often don’t have benefits like health insurance, like paid vacation. I mean, that’s certainly a challenge and I think that those are issues that drive a lot of people out of the freelance business because it’s so unstable in that way. Some people are married people or people who have a partner and they use their health insurance and that person has a more stable income and it’s good for the other person to be more flexible. But if you’re relying on yourself, a lack of paid vacation, lack of benefits, lack of retirement contribution funds… These are all things you might not think about when you’re 18 or 19, but then in your 30’s you’re definitely like, “What am I doing?”

So I think it takes a lot to stick with it once you realize those difficulties, and then of course things as boring as taxes. Taxes for freelancers can be hard to deal with, especially if you’re working abroad. The law is not very simple. It’s hard to find a simple tax program that’s going to help you do things the right way. So there’s a lot of nitty-gritty to it—the unglamorous, unexciting side of it. I mean, it’s wonderful to do the work that you want to do every single day but there’s a whole side of it that is a bit of a drag.

BRITTANY: So on the flip side, what would you say are the benefits?

SARA: The benefits are doing the work that you really want to do and doing it on your own schedule. It’s really amazing to think that every day you’re going to wake up and think of what’s most interesting to you, or something that’s exciting, or a compelling person that you want to talk with and then make all that happen and get to know that issue and really engage with it on an intense level. And of course there’re all different sorts of freelancing. I mean, people freelance on every possible issue, but I am talking about my life as a freelance foreign correspondent. It gives you a lot of freedom. I think freedom is probably the thing that a lot of us appreciate about the job.

BRITTANY: Tell me a little bit about the prep. Do you come up with an idea and then you have a certain newspaper or magazine in mind of like who you’re going to pitch it to, and if they don’t like the idea, do you go to another magazine? Tell me a little bit about how the pitching process works.

SARA: Well, pitching is really crucial to any freelancer. I’d say before I start talking about this that if anybody is considering freelancing internationally, I highly recommend sort of doing an internship or building contacts with editors at the places you want to publish before you start traveling.

In my case, I started working while I was still finishing my master’s degree and I did not really have contacts with editors back in the States at the places I wanted to publish and so it took me a lot of time to really get off the ground and establish those contacts; whereas if I had worked on establishing them before I came down to start working, I might have been in a better situation to start publishing sooner.

I feel that your relationships with your editors are so important because you’re trying to create something together, and as a freelancer your job can be really solo and isolating. I mean, you work on your own. You’re not in a newsroom. You see your peers or other journalists at events and social functions, but you’re not working with people every day. So that editor is your way to the larger world, and there has to be a lot of trust between you because you may be writing about a place that the editor doesn’t really know, or that they don’t have a really deep knowledge of, and that editor is going to be preparing your work for publication in an international outlet. So there’s got to be a really strong working relationship there.

When I first started pitching to people, a lot of times I would meet somebody who knew an editor at a publication and they’d gotten familiar with my work and they would put us in touch, because cold pitching a publication with no contact can be difficult. Editors receive so many pitches that they might not really have time to look specifically at yours. So networking and contact building are absolutely crucial, and I had never thought of myself as much of a networker when I started this job.

But when you like your job, networking is natural because you want to talk with people who are interested in and doing similar things. So you start to build up these contacts with people who are in the same field. And then once you get an editor to accept your pitch, you do the story, you send it over to them. I find that the first three or four times you work with an editor, you’re still really feeling out the situation, but if you get through that phase, then you can really start to build this relationship of trust where you put ideas back and forth and they’re responsive to you.

In my case, there were editors that I had worked with multiple times and when I think of a story or an issue, first I start to think, “Okay, this is happening. This is an interesting topic. This could be something that would work well for a story. And then I’ll think, well, how would I present it to make it interesting to outlet A, or how might it work for outlet B,” and normally I’ll just think of the editors that I know and think, “Okay, this story, the way that I want to do it, will probably work best for A.”

And they say yes or no. I think they say yes more than no because you get to understand what people are going to be interested in. Then once they say yes, I do the story, I send it, we go through the edit and then it’s published.

People ask me a lot of times, “Do you just write a story and then send it to an editor and ask them if they want it?” No, I don’t write my stories and then send them to an editor because writing a story the way that I do it is a really big investment of time. I can’t survive by investing my time in things that I then subsequently can’t sell.

BRITTANY: Right. Okay, so I guess I alluded to this before with the usefulness of the journalism degree but what about journalism as an industry, print journalism, specifically? I took a journalism class at Dickinson and my teacher would tell us all the time how print journalism is a dying industry. So what would your advice be to college students who are interested in pursuing a career in what a lot of people think is a dying industry?

SARA: I would say, think about how much you really love journalism. If you really love it, you’re going to get into it anyway. I mean, I always used to think it was so strange when people would talk about being in love with a job. But now I understand it. I mean, I love it. Will I be able to do it for my whole life? I don’t know. Would I like to? Yes, but I really just feel that this is the job that clicks for me and I know there are lots of other people out there who feel that way.

So whether or not the industry is dying, people are still going to go into journalism because they are going to feel a connection to it. But you need to really think realistically about the situation. I mean, your teacher was not kidding We have gone in recent years through massive layoffs at newspapers. Other organizations may not be growing or hiring as they once were. It’s a really difficult job market. At the same time, lots of people who went to graduate school with me are happily working as newspaper photographers and newspaper writers or magazine editors – while others went down different job paths. I mean, jobs do exist. You just have to accept that it’s an industry that is not flourishing at the moment.

But I don’t think that newspapers are going to end. I think maybe it’s not a death as much as a moment of profound change that is very traumatic to the industry. But the industry will continue onward. I think that people who are coming out of college, who really understand the consumption of news online and what it means to consume news through technology are a big part of defining how we’re going to consume news in the future.

BRITTANY: Right. Well, that’s the end of my questions. Do you think that there’s anything else that’s extremely interesting about you that you would want published?

SARA: I would just comment that if people are interested in international reporting and freelance, it’s not for everyone but I think it’s a great opportunity and really a privilege to get to know another country and another culture. I think it profoundly changes the way that you perceive the whole world when you’re just constantly immersed in a place that sees the world differently from the way that you once saw it. As a reporter, you become so involved with it that you start to see these details and intricacies and nuances that you would probably not see as a traveler or even as somebody working short-term in another country.

Of course you need to be realistic about whether you can financially survive in a place, in some cases people need to seriously consider their personal safety, and then whether living abroad long-term fits in with your greater life plans. If people are able to do it, I think that it can be a wonderful experience.

Recent Comments