It’s not easy to be a feminist and watch TV. I don’t deny there are shows that are making strides in their representation of women and non-normative people, such as Orange is the New Black, Parks and Recreation, Bob’s Burgers, etc. But despite these shows, television seems stuck in a rut. Though there is a lot available, shows stay rigidly within their genre and tend to market towards one single demographic. Cop shows work one way, sitcoms another, teen dramas are different from soap operas, and soap operas are different from prime time. So although the shows employ many different lenses, they remain clustered around a few primary ideas, showing but not embracing diversity in characters or life narratives. Watching through a feminist lens traps you in wanting to praise and encourage a show for the progress it does make but feeling disappointed by the conservative structures that TV can’t seem to let go of.

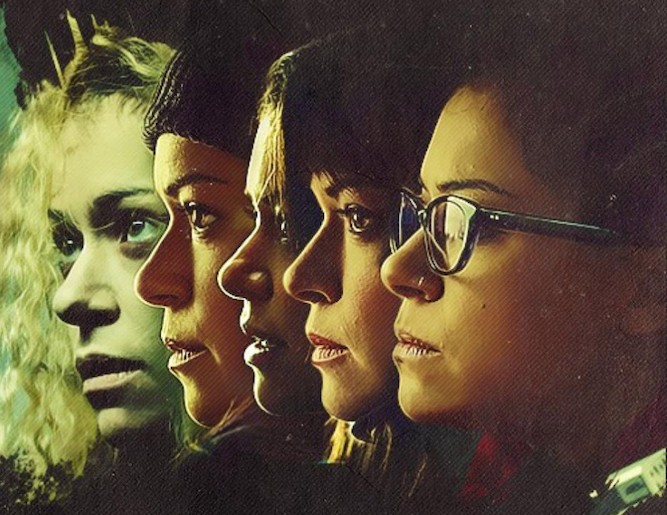

Orphan Black is a show that begins to deconstruct these ideas. For those of you who have not watched it, let me give you a synopsis (unless you want to watch it right now. Don’t worry, I’ll wait). Sarah Manning (played by Tatiana Maslany) is the first and primary character; the audience mostly follows her through the narrative, though in the later episodes this changes. Sarah was raised in the foster system, had an unplanned pregnancy, and ran away leaving her child in the care of her foster mother. The show begins with her return to NYC where her foster mother and daughter live, as well as her foster brother Felix (Jordan Gavaris). Sarah quickly learns that she is a clone, meaning that her DNA was either copied or constructed and that her body is technically owned by the Dyad group. She meets many of her “sisters” (as they call themselves) and joins them in trying to discover their origins. They attempt to sustain their lives while managing the unusual details of their existence and fighting for their autonomy against institutional and scientific control.

Through its story, Orphan Black establishes connections between the personal and the political that most TV shows don’t even attempt–and it does this while managing to maintain a multilayered narrative. Diverse characterizations for women–who are the majority of the cast–and men are central to the show. Unfortunately, Orphan Black is largely lacking in representations of people of color. The fact that a large chuck of the characters are all played by Tatiana Maslany because they’re clones is a contributing factor, but it by no means excuses the show for its white-dominated cast. This was a choice the show’s producers made, so though I praise the leaps that it is making I cannot say it does not have flaws, and I am not defending this significant gap in its representation of the human experience.

That said, Orphan Black creates a diverse representation of the female experience, including sexuality, career, class, religion, ideology, and motherhood status. Through learning about Sarah, her family and the clones–mainly Allison, Cosima, Helena, and Rachel–the audience is shown many different ways in which women live. Allison lives in the suburbs with her husband and two children. Cosima is a queer-identified student studying evolutionary biology. And Helena was raised in a convent and then brainwashed to kill people (pretty unusual, really). The audience is also shown the complex relationships between all of these women, and in particular the generational relationships of Sarah, her foster mother, and her daughter. The connections between women, such as those of motherhood or sisterhood (both biological and emotional), are major themes explored in the show. Strong bonds between women are not the subject of most TV shows at the moment, and it’s incredible to see these realistic and relatable female characters explore their relationships to each other, themselves, and the world. In addition, the show includes interesting male characters. In fact, the male characters are integral to the plot and are characterized just as the female characters are, as having different and complex identities. The show focuses on its female character while consistently bringing in male narratives and identities to complete the complex views of gender that appear in the show.

This diverse picture of identities is continued with the inclusion of queer-identified characters like Felix, Cosima, Delphine (a fellow scientist of Cosima), and Tony. I use the term queer to mean non-normative: anything that is against the traditional structures of society. Felix is Sarah’s gay foster brother who, while male identified, is welcomed into female spaces. He is not only openly gay with an actively queer social life but is defended as Sarah’s brother. His identity is not only outside heteronormative bounds, but his connection to Sarah is non-normative as well, as they are not blood relations.

The relationship between Cosima and Delphine (Evelyne Brochu) is also an amazing accomplishment of the show. After thinking about Cosima kissing her in the episode “Entangled Banks,” Delphine admits “Oh, like… I have never thought about bisexuality. I mean, for myself, you know? But, as a scientist, I know that sexuality, is a… is a… is a spectrum. But you know, social biases they, codified attraction. It’s contrary to the biological facts… you know.” This discussion of sexuality acknowledges both the social meanings and scientific ideas of sexual identity. The development of Cosima and Delphine’s relationship explores questions of identity, how identity changes, and what loving someone means. Tony, while only briefly in the show so far, queers the idea of female experience even more by being a transgender clone. His presence highlights that a female body does not always mean female person. Despite having identical DNA with his clone sisters, Tony identifies as a man and pushes against the gender binary and its limited view of sex.

Not only does the show incorporate all these identities as experiences of life, but it also connects them to political, social, scientific and other external institutions. Through the focus on reproduction and women’s bodies, the show explores how people and bodies are used in science, religion, and politics. The clones are inherently drawn into this tug of war because their bodies are the property of science. This also politicizes the lives of these women’s families. Their status as ‘object,’ not ‘person,’ raises questions about how women’s bodies in particular are commodified, often through their reproduction.

The questions of religion, science, and politics, however, do not end there. The show explores the relationships between these political institutions: where their goals overlap, when they’re in contest, how they view each other, and how their ideologies construct worldviews. This complex look at social institutions in connection with the individual is what makes Orphan Black such a smart and multi-layered show. Orphan Black is not trying to show the audience a single way to live, but is instead asking us to examine how the world around us works and what our place is in it. It shows life not as a contained event, but as connected to and influenced by larger external forces. This is exciting to me, that a popular television show would express such a complex world view.

Orphan Black is by no means the only example of television with diverse identities or political implications. Nor is it perfect, with every identity accounted for, and all voices heard. However, it is a show that attempts to establish the connections between personal and political lives. Its characters show a range of life experiences and identities and build relationships outside of a heteronormative structure. The show stands out against the Normative and promotes a more complex understanding of an individual’s relationship to society. In short, I think it’s worth a watch.

For more Orphan Black information, click here!

Leave a Reply