Have you ever played a game and thought to yourself “I really wish that dragon looked like Thomas the Train?” Well if you have, then you are in luck, because mods allow you to do just that. And if you have never even come close to thinking that, then fear not: there is still a mod out there for you. Mods are a great way to make a game more personal and entertaining since mods can essentially change almost any aspect of a video game into something the player wants. However, mods would be nothing without the developers that make the games they are for.

One developer that has been particularly prominent in the modding world is Valve. In fact, Valve was actually born from mods. In 1996, two Microsoft employees—Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington—left Bill Gates’ company to go and try designing video games. To do this, they acquired the software development kit (or SDK) for the Quake engine and began modding. In 1998, they released their debut product Half Life. Essentially just a large mod to the Quake engine, Half Life was an instant hit and later was actually used by other people to create one of the most successful mods in history, Counter Strike. The Counter Strike mod was eventually bought back by Valve and is now one of their most successful games, generating huge profits for Valve.

It’s obvious that a prominent part of Valve’s foundation is modding but there is one thing that sets them apart from other companies with the same selling point, such as Bethesda Softworks: Valve actively encourages the modding community. This encouragement has brought tons of benefits to the company, but this is not just a one sided relationship. As the rest of this post will explain, Valve’s encouragment for modding benefits modders by offering simple ways to create mods through things like creation kits, quick and easy ways to access and share mods through the Steam Workshop, and by providing players with a wide variety of mods. At the same time, modders provide value to Valve by providing the company with “free labor” and increasing the value of its games through modders’ creation of “complements.”

Video of mod that turns dragons into trains in Skyrim, By Gampo

In order to fully understand Valve’s approach to the modding community, one first has to know what a mod is. The issue with defining mods, however, is that there are so many different forms they can take. Mods can be anything from an enhancement to a game’s graphics to the creation of an almost entirely new game via the original game’s code, as in the case of Half Life. This is why the best definition of what a mod is needs to be rather broad. Walt Scacchi, a senior research scientist at the Institute for Software Research, gives a great and widely accepted description of what a mod is in his article “Computer Game Mods, Modders, Modding, and the Mod Scene” where he states that a mod is basically just “a legal change in pre-existing code that creates something new.” Now that a definition is in place, we can explian how mods benefit Valve’s community and Valve themselves can be explained, starting with community benefits.

Valve’s encouragement for modding has benefitted the community by allowing players to easily create mods through programs like creation kits and SDKs. One way Valve has encouraged modding has been through the release of SDKs for certain games. SDKs are essentially development tools that allow its user to create applications within a game. A second way Valve has encouraged modding is through the release of creation kits for certain games. A creation kit can be downloaded upon purchase of a game that has one associated with it. Upon downloading the creation kit the user can then edit almost anything they want in the game. The biggest benefit of using the creation kit to mod is that the mods a user creates are not stored in the game’s files. They are instead stored separately, so that if a user edits something in a game that makes it run incorrectly or messes up a certain part of the game’s engine, the entire game is not destroyed. These programs Valve has created greatly benefit their community by making it is easier than ever to create mods. Take the example of Skyrim. Once someone has downloaded the Skyrim creation kit from Steam anyone can take game models such as walls, characters, items, or even buildings and build entirely new creations quickly and easily with them. Since Valve provides people with the necessary software to mod right off the bat, members of the community that want to mod do not have to spend hours figuring out how and download outside software; instead, they can just boot up Valve’s programs and have the ability to create any mod easily right then and there.

Making modding easier is not the only benefit these programs have had for the community, they have also made it possible for almost anyone to mod. Things like creation kits have made modding rather simple and intuitive; one no longer has to be a wiz with computers to create a mod. Instead the would-be modder can just boot up his or her creation kit and be ready to create. Creation kits also mean that new or rather unskilled modders no longer have to worry about destroying the game they are playing since everything they add or create will be stored separately. Valve’s encouragement for mods has made modding simpler and easier than ever, which is a huge benefit to people who play their games and want to mod. But creating mods is not the only thing Valve has made easier; they have also made sharing and accessing mods easier than ever.

Valve’s encouragement for modding has benefitted the community by providing them with easy ways to share and access mods through the Steam Workshop. In 2008 Valve released the Steam Workshop for their game client Steam with the intentions of creating a way for people to easily share and access mods they create themselves or want to use, and it did just that. The Steam Workshop was an instant success and people immediately began sharing their creations. Players no longer had to scour the internet looking for one specific mod they wanted; instead, they could just log on to the Workshop and search for it using the search tool. In fact, the Market not only made finding particular mods easier, it made discovering new mods easier too. The Workshop provided players with ways of browsing the top and newest mods for their favorite games quickly. Once a player found a mod they wanted, he or she could click the subscribe button for that mod and whenever the modder came out with an updated version of the mod it would update automatically.

The Steam Community Workshop not only made accessing mods easier, it made sharing them easier too. The Workshop provided an easy way for modders to share their creations since they could just post them for others to find them. All of their creations were also easy for the creators to access within the Workshop so they could update them at any time. The Workshop also provided modders and non-modders with a simple way to share their favorite mods. People could “like” mods and send the links to them to their friends, making it easier than ever to share their favorites.

The final benefit Valve’s encouragement for mods has provided the company’s community is that it has created an expansive variety of mods offering a personalized experience for almost any player. With the implementation of the Steam Community Workshop, creation kits, and software development kits, it has become easier than ever to create, access, and share mods. This simplicity has lead to a seemingly endless supply of mods meaning there is a mod for almost anyone in any game. This allows players to make the gaming experience their own and tailor it to the way they like it, which is what mods are really meant to do. But the programs Valve has implemented have created such a vast quantity of mods that personalization has been taken a step further. Now players can basically make entire games into what they want them to look like or what they thought the game should look like.

It is great that Valve has encouraged modding and thus brought so many benefits to their community but they probably would not have been as encouraging if mods did not benefit them in some way. Valve’s encouragement for mods has benefitted them because modders act as a kind of free labor. As stated before, the definition of mod can be rather broad; therefore, a mod is not necessarily just an addition to a pre-existing game. Modders quite frequently actually create mods that fix bugs in a game or enhance certain other aspects of the game, such as graphics. These fixes or enchantments cost nothing to Valve and greatly improve the gaming experience. Thus, modders act as a type of legal free labor for Valve. In fact, according to Hector Postigo, an associate professor at Temple University, modders actually save game developers upwards of $2.5 million dollars a year in labor costs. Since Valve has encouraged mods through things like the Workshop and SDKs, the number of modders creating these fixes is constantly growing. This means that Valve’s savings from free labor can only increase.

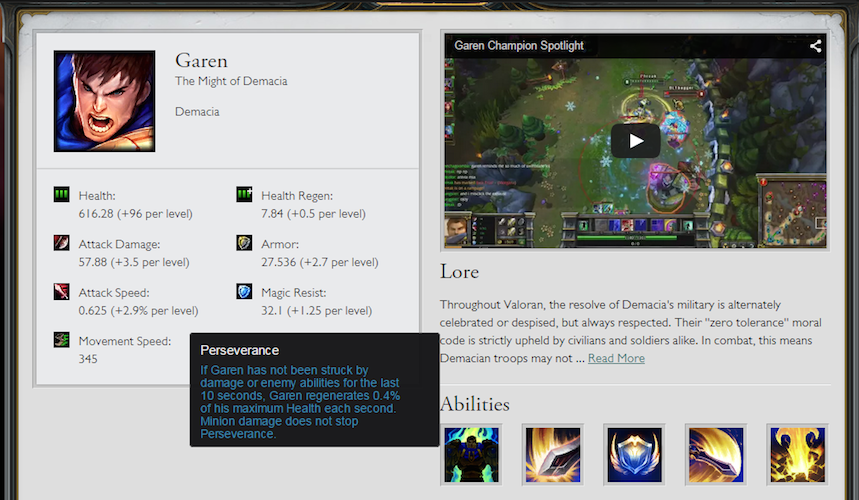

Modders do not only benefit Valve by being free labor, however; they also act as “complementors” to Valve’s games. As explained earlier, Valve’s encouragement for modding has made it easier for almost anyone to mod, thereby increasing the number of modders out there. This benefits Valve because each of these modders offers their own “complements” to a game. How these contributions work to increase the value of a game is explained by Lars Bo Jeppesen, a professor at Copenhagen Business School, in his essay entitled “Profiting From Innovative User Communities: How Firms organize the Production of User Modifications in the Computer Games Industry.” He describes modders as being “complementors” who add complements (mods) to a game that a developer has created. They are complements because they add features that enhance the game. Modders/complementors can only add complements to a game though because the mods or complements they create are not crucial to playing or experiencing the game. When enough complements have been added to a game, the game will increase in value, and this will in turn most likely lead to an increase in sales. However, this does not mean that when a game acquires a lot of complements Valve will increase the price of the game. This is a huge benefit for Valve since more game sales means more profit. Sounds like a pretty good deal to me.

Gabe Newell, Co-Founder of Valve

A great example of this is the Fallout series, specifically the games before Fallout 4. Though Fallout is not a Valve-developed game, Bethesda Softworks, the game’s developers of Fallout, use Steam to sell and offer mods for their games. The Fallout series is available on all platforms including PlayStation, Xbox, and Steam (Valve’s game platform), but it consistently sells better on Steam than any platform. Why could this be? This is because Valve is the only one that offered mods or “complements” for these games prior to the release of Fallout 4. Because Valve offered the ability to create and download mods to their Fallout games, people would add “complements” to the game, increasing the game’s value on Steam. Thus the sales for Fallout on Steam were greater than the sales on other platforms. The value of games on Steam have thus greatly increased due to Valve’s encouragement for mods.

Many competitors such as Sony and Microsoft have rivaled Valve in game development but Valve has always dominated the modding scene. They figured out what works and know how to use it to create a simple, enjoyable experience for those who want to mod and profit off of the mods these people create. The key to doing this was releasing products that encourage modding such as SDKs, creation kits, and the community market. These encouragements benefitted modders and game players by offering simple ways to create, access, and share mods while benefitting Valve by giving them a source of free labor and increasing the value of their games. A Half Life 3 mod (or full game) would most likely benefit Valve and their community a great deal too.

Recent Comments