Fresh Off The Boat is one of the newest ABC sitcoms. It comes to the network from Nahnatchka Khan, who based the show off of chef Eddie Huang’s memoir of the same name. Though the title suggests a family of immigrants just arriving to the United States, the show follows the lives of the Chinese Huang family after their move from Chinatown in Washington D.C. to Orlando in the mid-1990’s. It centers on their struggle to assimilate to a new culture, while also having much more similar sitcom tropes such as difficulties fitting in at school, challenges running a successful business, and issues surrounding parenting.

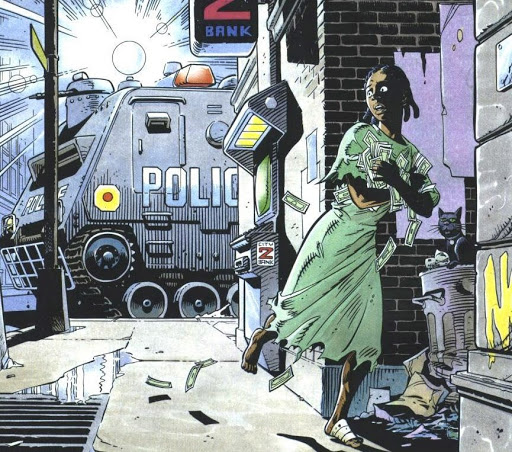

Though the show revolves around hip-hop fanatic, 11 year old Eddie (Hudson Yang)–who, despite being young, has a sharp wit to him–the episodes all have the theme of assimilation central to their plots in one way or another. Eddie, for instance, is trying to fit in with the kids around him in school. His mother (Constance Wu) is trying to fit into the new white culture that she has found herself surrounded by. And the father (Randall Park) is trying to discover the correct way for his restaurant to fit into the community and garner patrons. Despite the obvious racial conflicts in the show, this is a series based much more on exposing the ridiculousness of people who believe stereotypes rather than on making fun of immigrant culture.

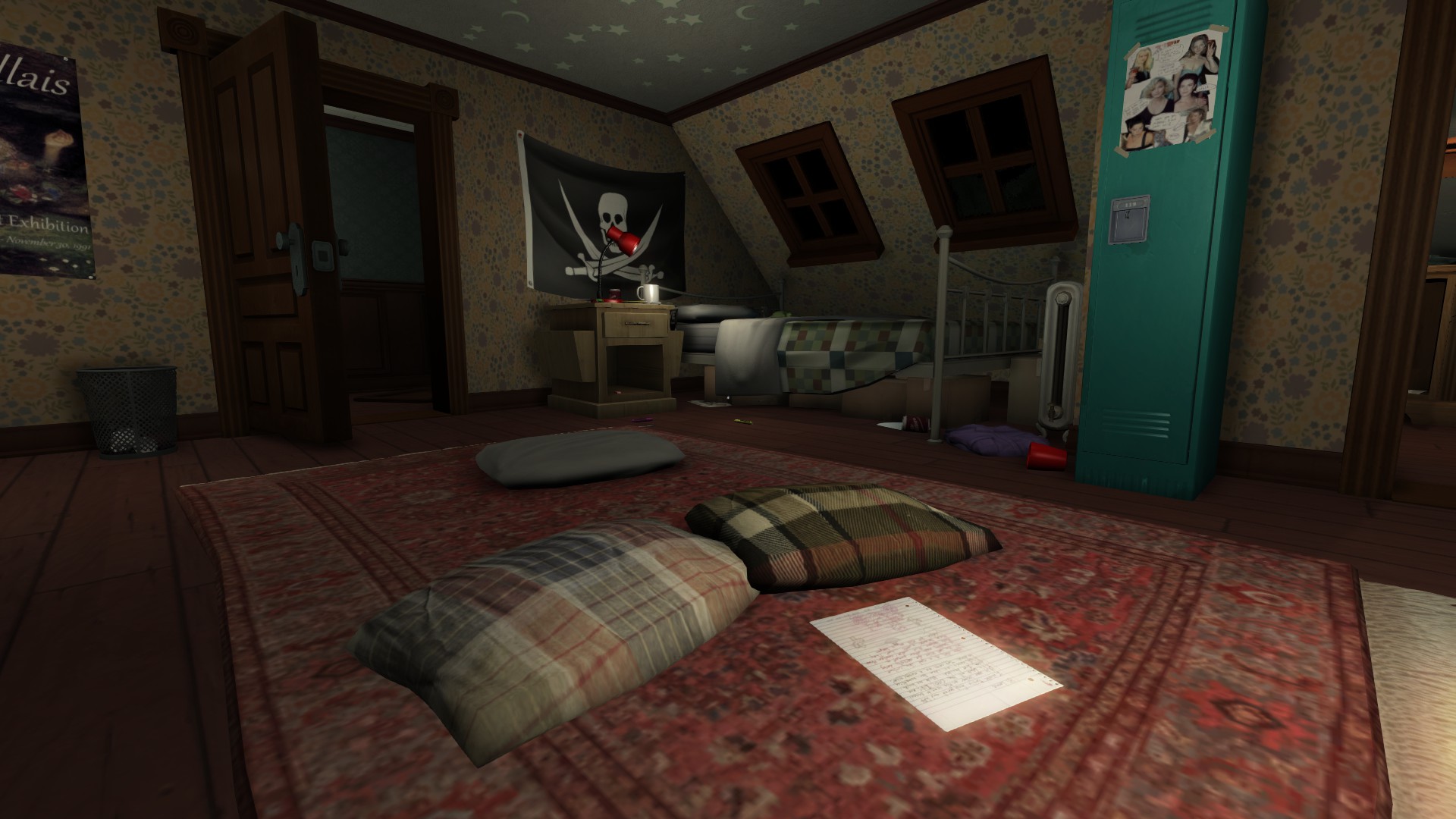

While the show has deep-rooted racial dynamics, it also plays on much more typical situational comedy tropes. In addition to standing out at school because he is Chinese, Eddie goes through the typical adolescent struggles of trying to make friends or being cool (through the music he listens to or, in one instance, by getting his hands on a porno). Similarly, his mother has trouble adjusting to her new white housewife neighbors and eerily calm grocery store, but also has to go through the trouble of finding a job and figuring out how to raise her children when they resist a lot of what she wants from them. Eddie’s father, meanwhile, wants the best for the family, but is also constantly dealing with issues in his restaurant. Most of the comedy around him is more about professional failure and the difficulties of being a restaurant owner and a passive dad, which has little to do with his race. His involvement with American culture is exemplified by his attempts to get his western themed restaurant off the ground by appealing to customers’ whiteness.

The strongest part of the show is the character dynamics. The Huang family has three young children, with Eddie the most prominently featured character. Eddie is sort of wise beyond his years–a trait emphasized stylistically through regular voiceovers from his adult self–and has a smart aura about him. He is a really likeable character because he is trying to make friends and do all the things he wants to as a young child but this causes conflicts with his parents, namely his mother. The clashing of cultures between his Chinese parents and his assimilation into American culture is the perfect platform for the majority of the comedy of the show. While he also faces the familiar trouble of finding friends and fitting in at a new school, a lot of the comedy geared towards an older audience arises from his overbearing mother and goofy father. His father is constantly trying to find ways to successfully run his western-themed steakhouse and can be seen as somewhat of a weaker character with his reluctance to confront his employees and children. He typically plays second fiddle to his opinionated wife when it comes to making decisions. The mother, on the other hand, demands attention in a way that puts her in awkward situations that draw much of the laughter. The youngest brothers are mostly just there for comic relief from the rest of the show, which sometimes deals with the tougher issues. The final member of the family is the grandmother, who rarely speaks and has a somewhat indeterminate role on the show.

The show is chalk-full of 90’s references. Part of the excitement of watching it is in the nostalgic feeling one can get. The music on the show is almost all old-school rap, as that is all Eddie listens to. Eddie is also a basketball fan and sports a Shaquille O’Neal Orlando Magic jersey in one of the first episodes, circa the mid-90’s. The focus on adolescent boys also enables lots of references to things like Hi-C Ecto Coolers, Lunchables, VHS tapes, and Ella Macpherson to be prevalent. Despite middle-school-age boys’ issues being one of the main plot drivers on the show, the frequent references to things of the past means this show is aimed more at an older audience who grew up in this time than contemporary viewers who are the same age as Eddie.

The problems around parenting, the efforts of the characters to fit into the white American culture, and the constant 90’s references suggests that the ideal viewer for the show is very particular. Given the issues being brought up on the show, it would appear to appeal to either parents, immigrants or ethnic minorities, or young adults who grew up when the show was taking place. That being said, I think part of the idea behind the show is also to expose the dominant white culture in the American society to the things people go through when they are not a part of this group. Thus it could be useful for just about every American to give it a watch for more than just a laugh. Though the writers do a really good job balancing comedy, moral lessons, and racial issues in each episode, the declining viewership of the show since its premier indicates audiences have not taken to this idea, despite the high praise the show has received from critics.

Fresh Off The Boat is a groundbreaking show simply based on the fact that it centers on Chinese-Americans, a group that has rarely been seen in sitcoms. Its brilliance goes much deeper than this though. It is a refreshing comedy with a unique take on racial issues that seeks to undermine a lot of the Asian stereotypes in this country. In this way, it is a little ahead of its time and, as with a lot of more clever, critically acclaimed sitcoms, it is not a ratings smash, since it is trying to do more than just be silly or show slapstick humor. Fresh Off The Boat is a really strong show that consists of excellent writing and acting. It is hard to have the star of a primetime sitcom on network television be a young child, but Hudson Yang is more than up to the task of leading this show in his hilarious and deep portrayal of Eddie Huang. Hopefully the viewership can climb in the second half of the first season because it would be great to see this show picked up for future episodes as it tells a very compelling story surrounding an Asian-American family and the issues they face everyday.

Recent Comments