Educational Injustice: Forming Alliances to Create Progress

The Black History Photographs Project is a partner project with Hope Station uncovering the hidden histories of the Black Carlisle community, specifically churches, schools, historical sites, and family photographs. Hope Station’s mission “seeks to lift up the entire neighborhood by tackling our most difficult problems through education, technology, job development and most importantly, teaching our children to become leaders by learning to respect themselves and others.” Hope Station is allied with The Cumberland County Historical Society, whom allows students and other Carlisle residents to utilize their archival resources. The goal of this service-learning course is to ensure that students are able to grasp an understanding on the many social, political, and economic injustices experienced by black bodies daily. This particular project grapples with the educational injustices endured by the local black community of Carlisle. Specifically, we focused on the histories of the “colored” schools in Carlisle, The Lincoln School and Wilson School, as well the historically local Black churches, such as The Shiloh Baptist Church and Bethel A.M.E. Church. Historically, churches were the spaces used to foster education for local black communities. Through the methodology of archival research, this project essentially closes the gap between the intellectual and the local black community, by providing them with access to historical information on their ancestral achievements and heritage.

“Colored Schools”

Wilson School

Wilson School

Lincoln School

Lincoln School

One aspect of this project focused on the educational injustice that was endured by the local black community, historically–the Lincoln School and Wilson School. Historically, evidence has proven that for African Americans, education (or lack thereof) was another method employed by white supremacist to keep black citizens subjugated. However, after entering the service learning project with Hope Station, one can conclude that although there are not legal policies, such as Jim Crow Laws, there is still this educational injustice happening right in the local black community today. While my main methodology was archival research, completing this project took much self-reflection in regards to realizing what was important me. In order for me to grasp an understanding on the importance of social justice work, I revisited my hometown, which is similar to the black marginalized community here in Carlisle. I came to the conclusion that a specific social justice issue that is very important to me is both educational and distributive injustice that black communities face, which hinder the potential success for black individuals in these communities. This recognition definitely helped in terms of organization because I knew exactly what to research during the next couple of weeks.

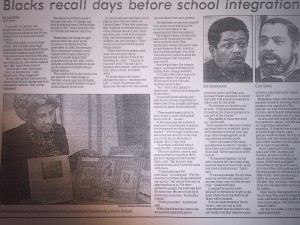

Archival research enabled me to uncover the origins of the two “colored” schools in Carlisle, individuals that worked at these schools, as well as the many problems school board officials faced during this time period. In short, the first “colored only” school actually “[began] in the basement of the African Church on Pomfret St., now Bethel A.M.E” (Development Of Education for Colored in Carlisle), by four members of the The Lady Benevolent Society in 1836. Due to, of course, the racial tensions in Carlisle, the first school for black children was underfunded and overcrowded. Despite this, however, Miss Bell, a white woman who was asked to come help teach, taught the students skills such as reading, religion, and sewing. Historically, this alliance between white teachers and black school is evident as white teachers from the north often migrated to the south to teach black students. Noting that Miss Bell was a white woman highlights this idea of alliances that were needed for social justice to be successful. It is not just about the black the organization, but the allies that helped make resources available to these organizations. Shortly after the Lincoln School had been built, another public school, known as the Wilson School, opened in 1890. Initially serving as a high school, the Wilson building would soon become an elementary school for only black children. Typical of many segregated schools in parts of country, these two Carlisle schools lacked resources that were accessible to their white counterparts. For example, in an article entitled “Blacks Recall Days Before School Integration”, a young African American student asked “Why couldn’t their classes have a movie projector, like white students say they had at their school? (Miller). This show the distributive injustice that was endured by African American schools, which often hindered the success of black students.

Archival research enabled me to uncover the origins of the two “colored” schools in Carlisle, individuals that worked at these schools, as well as the many problems school board officials faced during this time period. In short, the first “colored only” school actually “[began] in the basement of the African Church on Pomfret St., now Bethel A.M.E” (Development Of Education for Colored in Carlisle), by four members of the The Lady Benevolent Society in 1836. Due to, of course, the racial tensions in Carlisle, the first school for black children was underfunded and overcrowded. Despite this, however, Miss Bell, a white woman who was asked to come help teach, taught the students skills such as reading, religion, and sewing. Historically, this alliance between white teachers and black school is evident as white teachers from the north often migrated to the south to teach black students. Noting that Miss Bell was a white woman highlights this idea of alliances that were needed for social justice to be successful. It is not just about the black the organization, but the allies that helped make resources available to these organizations. Shortly after the Lincoln School had been built, another public school, known as the Wilson School, opened in 1890. Initially serving as a high school, the Wilson building would soon become an elementary school for only black children. Typical of many segregated schools in parts of country, these two Carlisle schools lacked resources that were accessible to their white counterparts. For example, in an article entitled “Blacks Recall Days Before School Integration”, a young African American student asked “Why couldn’t their classes have a movie projector, like white students say they had at their school? (Miller). This show the distributive injustice that was endured by African American schools, which often hindered the success of black students.

In light of what we have been learning about social justice this semester, this project definitely connects to the both educational justice and distributive justice for black citizens. Social justice leaders have worked to tackle the educational injustice endured by the black community. Historically, the development of colored schools in this country was a harsh one. The education board, in the North and South, were controlled by white government state funding. Government officials feared that educating African Americans would “challenge their white supremacy…therefore Black schools received far less financial support than did white schools. Black schools had fewer books, worse buildings, and less well paid teachers.” (Virginia Historical Society). As a result, local organizations such as the Black Panther Party developed literacy and other enhancement programs within the black community. One can argue the ability to read would allow for black individuals to fully claim their citizenship, as they would be able to both interpret and partake in policies that once kept them oppressed. What is important about the Black Panther Party tackling educational injustice is that there programs would not have been as successful without the help of other outside organizations—whom were usually white activist. Howard McGary, author of Racism, Social Justice, and Interracial Coalitions highlights the importance of having allies in a works of social justice. McGary states the constant racial tensions between black and white citizens is what has ultimately put a damper on the progress of social justice movements. He states that “is not enough for whites or African-Americans to be inclusive with it comes to intellectual contributions that from various cultures” (McGary 203), but should instead join with the marginalized community as well and work together without racial tension. This is apparent in our project as the local black organization, Hope Station, paired with the Cumberland County Historical Society, in order to make available historical information to the wider community.

In addition to its link to interracial coalitions, this project also resonated with the social justice movement that called for an African-Centered education. I found in my research that during the desegregation of public school, delegates argued for maintaining black teachers within schools. The importance here is that black teachers are thought to help boost the self-esteem of black students within these schools. In addition, having an African centered curriculum would bring the histories of the black community to center of education.

Churches

Archival research, a kind of primary research method conducted is the main method of examination I employed in my when search for Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and The Shiloh Baptist Church Carlisle. With the use of the filed electronic archives and tangible archives from The Cumberland County Historical Society, along with the use of the online management museum software provided by pastperfect.com I was able to find a large quantity of historical entities dating back to the 1800’s. Within my research I was able to find extensive gripping facts on both historical sites. Bethel A.M.E Church, located on 127 East Pomfret St in the community of Carlisle, Pennsylvania initially started with a small group of African American believers of Christ that would congregate together and have prayer meetings in the homes of who ever had available space. As time progressed and continued to take place in the year of 1820, the number of people consistently participating in weekly bible study largely expanded. What was formerly known “Pomfret Street A.M.E Church” transitioned into the new name Bethel A.M.E and continued to provide the community with one of the only safe spaces for praise and worship. Beyond providing the members of the community with a sacred religious space, the church acted as a space for encouraging conversations around difficult topics, creating an educational space for children, acted as a medical care taking facility. Religious institutions were very important to the Social Justice movement. Underwood attest to this explaining, “Not forgotten are the days of meetings within churches, such as the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which served as a rallying point for civil rights activities and focal conversations during the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement and was consequently bombed”.

The church also functioned as an academic arena, where the studies of the youth were made a priority. Miss Sarah. Bell, a white teacher from The “Negro Public Sch ool” utilized the basement as a room where students can learn about English, Math, History, and Science. Black children and other children of color were not granted the access to decent education. Sarah Bell acted as a white ally with Bethel A.M.E and acted as a key component in cultivating an alliance with the church. The church supplied a space for children of color to get the education they deserved, and further more wouldn’t fully receive in an underfunded institution. The class was able to delve into the significance of Social Justice and interracial coalitions. In chapter 12 of Howard McGary’s book Race and Social Justice. Within his work he examines how race and social justice play a role in the American narrative, but in chapter 12 he is specifically grappling with the social politics that is attached to interracial coalitions. One of the important aspects of interracial coalition, or opening spaces committed to social justice issues in reference to opening up space to non-people of color is what McGary explains as, “Any realistic proposal for ending the injustices or perceptions caused by racism must be based upon creating trust and bonds of commitment across races…Without a shared sense of community there can be no justice. And without justice there can be no peace”. This is important to keep in mind because the relationship between the black church and the white teacher is an examples of interracial work. Beyond opening up the space to Miss Bell, Bethel A.M.E acted as a provisional shelter and a medical facility in the course of the Civil War. Reverend Lawrence Chappell Henryhand, Bethels’ 64th delegated pastor has been under leadership since the earl 1990’s to present day. Under his leadership the church has been able to successfully thrive and make active change that continue to maintain the well-being of the church.

ool” utilized the basement as a room where students can learn about English, Math, History, and Science. Black children and other children of color were not granted the access to decent education. Sarah Bell acted as a white ally with Bethel A.M.E and acted as a key component in cultivating an alliance with the church. The church supplied a space for children of color to get the education they deserved, and further more wouldn’t fully receive in an underfunded institution. The class was able to delve into the significance of Social Justice and interracial coalitions. In chapter 12 of Howard McGary’s book Race and Social Justice. Within his work he examines how race and social justice play a role in the American narrative, but in chapter 12 he is specifically grappling with the social politics that is attached to interracial coalitions. One of the important aspects of interracial coalition, or opening spaces committed to social justice issues in reference to opening up space to non-people of color is what McGary explains as, “Any realistic proposal for ending the injustices or perceptions caused by racism must be based upon creating trust and bonds of commitment across races…Without a shared sense of community there can be no justice. And without justice there can be no peace”. This is important to keep in mind because the relationship between the black church and the white teacher is an examples of interracial work. Beyond opening up the space to Miss Bell, Bethel A.M.E acted as a provisional shelter and a medical facility in the course of the Civil War. Reverend Lawrence Chappell Henryhand, Bethels’ 64th delegated pastor has been under leadership since the earl 1990’s to present day. Under his leadership the church has been able to successfully thrive and make active change that continue to maintain the well-being of the church.

The Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church of Carlisle, located on the corner of Lincoln and North West Street was created out of the undeveloped Baptist Church by Reverend William Bell in 1868. With what began as a small group of members of the black community of Carlisle meeting in different locations to pray, read the bible, and discuss the word of the day their meetings quickly turned into a black congregation. From there Shiloh Baptist Church became one of the main spaces for black people of the Carlisle Community to comfortably worship. As the organization continued to develop and grow Reverend at the time W.A.D Peck found himself drawn to the connection between religion and education. As his interest he grew he decided to take the initiative to construct and teach at the first church school in Carlisle Pennsylvania. W.A.D was a significant in bridging the gap between the black intellectual and the black community of Carlisle. McGary explains the importance and the responsibility of the African American intellectual when he says, “Intellectuals must join with the wider community and resist the temptation to acquiesce in wrongdoing they did not cause it”. Reverend Peck plays such a vital role in making sure that a space exist where intellectuals and people of the community can come together and bond, talk about different experiences, and network. The church school provided the community with a space to learn about topics presented during the week, along with a space to share ideas, and provide constructive criticism for the church and school. Lastly they specifically provided the youth of the church with a platform to explore their intersecting identities. Currently under the leadership of Pastor Dr. Williams E. Jones, The Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church has been completely renovated and remodeled. A library has been implemented in the space and has provided members of the congregation access to different kinds of literature. Along with the renovations the Church has added several new organization, such as The Young Men’s Usher Board, The Bud Choir, The Library Committee, The Scholarship committee, The Flower Guild, and The Board of Education. Shiloh continues to serve as a place where people the community can praise and worship in a comfortable space amongst the members in their community.

Moving Forward

The Black History Photograph Project has already provided historical information in regards to the local landmarks, and achievements of the Black community. In order to continue this project we would suggest that a small volunteer group can dedicate their time to archival research in the name of cultural preservation. For example, by creating a blog that allows members of the Black Carlisle community to update their experiences that were not available in the images provided. In light of the educational injustices faced by black people daily, the need to continue this type of service work will bridge the gap between local Black intellectuals and the wider Black community.

Citations

Edwards-Underwood, Kimberly. “#Evolution or Revolution: Exploring Social Media Through Revelations of Familiarity.” Black History Bulletin 78.1 (n.d.): 23-28.

McGary, Howard. “Racism, Social Justice, and Interracial Coalitions”. Race and Social Justice. BlackWell Publishers (1999).pgs.196-212

McGary, Howard. “Chapter 12.” Race and Social Justice. 1st ed. Malden, Mass: Blackwell, 1999. 293.

http://www.hopestationcarlislepa.com/mission.php

Leave a Reply