Rentierism as an Isolated Factor: Effective on its Own?

The rentier model describes a state whose economy relies on outsourcing the advantages of its land abroad. The outside states are “renting” the rentier state’s property because that state does not primarily use its land for itself. The benefits of this land can be either military location or natural resources. In the case of MENA, almost all the rentier states are dependent on oil extraction. The states that are not oil rich export their labor to these states, so the entire region’s fortunes are tied to these rents.

It is commonly understood that rents have negative impacts on democratization. The rentier model allows the government to have an excess of power while lessening that of the people, whether through the absence of taxes, military repression, or other methods. What is less understood is which specific qualities of rentierism are sufficient to trigger the prevalence of authoritarianism.

As Ross’s article explains, rentierism, though conceptualized by MENA experts, is not exclusive to the MENA region. Other regions, namely sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, have large oil deposits and states which fit into the rentier model. Ross’s article makes clear that the negative effects of rentierism are highly general. In other words, they are not limited to any one region; they apply universally. Income prior to the discovery, not geographic location, of oil wealth is the factor that has the biggest impact on negating the authoritarian effects. Nevertheless, it is notable that Latin America had a wave of democratization in the 20th century, which MENA was resistant to. The question then becomes: is there something specific about MENA oil rents which cause its perpetual authoritarianism? Or is there something else in combination with rentierism that yields this result? Personally, I tend to think the latter.

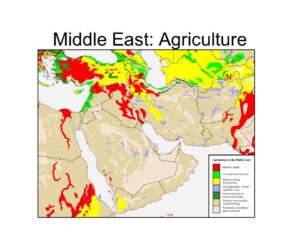

Another key principle in Ross’s article is the idea that mineral exports are particularly prone to promote authoritarianism. He tests these minerals against agricultural exports and finds that they do not produce the same outcomes. One theory behind this phenomenon is that agriculture’s labor intensity lends itself to higher employment levels and increased specialization. Conversely, oil extraction employs few and does not require specialized labor. Moreover, agriculture does not enrich the government to the extent oil does. In this way, agricultural exports increase the power of the workforce and limit that of the government. The Middle East is restricted in this area, not able to produce large quantities of agricultural goods due to its topography.

This is not to say that its lack of airable land has caused MENA’s reliance rentierism nor that the presence of farmable land would deter such practices. Rather, this points to factors unique to MENA which drive it to rely so heavily on oil, in turn causing enduring authoritarian. More plainly, it is impossible to study rents in a vacuum. Though their effects may be generally applicable, what triggers them or makes them so severe is more difficult to grasp. Many things which may initially be perceived as outside factors can be explained by rents. For example, as previously discussed, unemployment and a lack of specialization are tied to rents through oil’s low labor requirements. However, land quality is one characteristic that is innate to the region and cannot stem from rents. It therefore functions as a useful example of a confounding factor in the rentier model and its consequences.

Ross, Michael L. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics, vol. 53, no. 3, 2001, pp. 325–61. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25054153.

Ed Webb Said,

October 4, 2023 @ 6:26 pm

Very persuasive and clearly written.