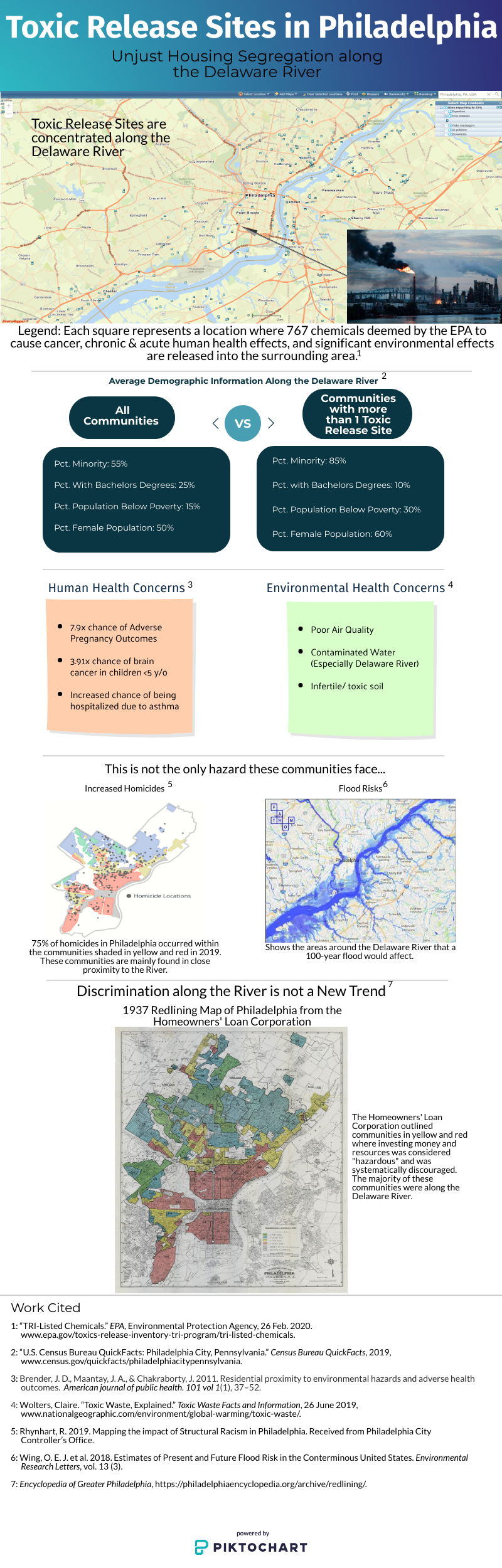

Philadelphia is a city that is home not only to a variety of people, but also a variety of industries producing all sorts of waste. One major environmental problem that is occurring in Philadelphia is toxic chemical release into the surrounding environment. As is often the case, a popular place to dump waste throughout America is within waterways for its convenience of taking the unwanted, hazardous material away from the production site (Wolters, 2019). Many of the EPA Toxic Release Inventory Sites in the city are located in close proximity to the Delaware River, especially the portion dividing Philadelphia and Camden, NJ (EPA, 2020). These chemical discharges are creating major health concerns, primarily causing adverse pregnancy outcomes and increasing the chance for children under the age of 5 of developing brain cancer, both of which can ultimately be fatal (Brendar et al, 2011). While even the slightest chemical exposure can be detrimental, the communities along the river are disproportionately impacted. Many studies have determined that in Philadelphia, those communities are minority groups, such as low income, people of color who have a high school diploma on average (U.S. Census, 2019). As the released chemicals are found in the air, water, and eventually soil, it is very easy for people in close vicinity of toxic release sites to be exposed to these toxins (Wolters, 2019). While the results are surprising, redlining and housing injustice in Philadelphia follows a historical pattern and consequences will be felt well into the future (Rhynhart, 2019; Wing et al, 2018). Based on evidence found and presented, the management of toxic chemical release is not environmentally sustainable and is inequitable because minorities are those who really bear the disproportional weight of its consequences.

April 30, 2020

Prof. Michael Heiman (Emeritus)

May 1, 2020 — 3:24 pm

Toxic Sites Philadelphia:

Lots of work in nearby Chester, PA as well as Philadelphia–sSe work by Environmental Justice Network, led by Mike Ewall. They also work across PA and the Northeast, and especially in the Philadelphia Area–active for the past 20+ years and leading local group on EJ in the community. Particularly useful for going beyond documentation of EJ toxic impact and working on community organizing and progressive solutions. Has college interns working with them, including several from Dickinson in the past.

http://www.energyjustice.net/about

http://www.energyjustice.net/mikeewall

http://www.energyjustice.net/contact

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:25 pm

Thank You for the information and contacts! This is definitely something I plan on looking into.

Hiba

May 1, 2020 — 5:46 pm

Great investigation of toxic release sites in relation to housing segregation in Philly. Really liked how you also explored other hazards the communities along the river face, it brings everything together.

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:13 pm

Thank You! It was important to show how these communities are systematically oppressed and some historical references to explain how embedded it is in Philly politics.

pikturne

May 1, 2020 — 6:08 pm

Really cool how you tied in historical discriminatory housing practices; shows how this is very much a systematic issue. Furthermore, I assume that these groups also have a lower chance of having access to healthcare. I wonder if that has worsened the effects caused by toxic release sites. Have local governments acknowledged this inequality? Have they done anything to mitigate the issue?

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:22 pm

I have not done research on if these communities have a lower chance of healthcare; this is a good question. As for acknowledgment, local governments in neighborhoods around Philadelphia and organizations within the city have made efforts to raise awareness and mitigate the issue with little success. Far more frequently than acceptable, there have been malfunctions and mistakes within facilities with catastrophic consequences. For example, the facility seen in my thumbnail exploded soon after that photo was taken, dumping 5,000 pounds of chemicals into the Schuylkill River which could not be regulated since that was not a foreseen event.

Anonymous

May 1, 2020 — 6:15 pm

Thanks for this informative project. There are so many considerations for planners and policymakers outlined in the project: environmental conditions, public health and housing. I am wondering if you disaggregated the data to determine the composition of minority groups and establish whether a particular racial/ethnic group among the people of color faced greater hazards or impacts.

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:30 pm

While I did not look too much into the composition of the minority groups, I did notice that the most strongly effected racial group was the Hispanic population. While all racial minorities seemed to have an increase risk for those listed health concerns, Hispanic Females were consistently impacted more.

Claudia

May 1, 2020 — 6:18 pm

Your decision to incorporate the homicide maps, as well as the redlining maps was really smart. It helps me understand the many compounding and intersecting injustices in this area. I am curious about the redlining map you included. Do believe that the maps were instrumental in the locating of the toxic release sites?

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:35 pm

Thank You! Weather consciously or subconsciously I do think maps like the one from the Homeowners Loan Corporation helped influence the location of these facilities and thus the toxic release sites. This began a positive feedback loop because once they began to experiencing increased medical problems within those communities, they became even more undesirable to invest in.

Brendan

May 1, 2020 — 6:23 pm

As a suburban Philadelphia resident, I drive by this area frequently while home on breaks. I’ve never stopped to consider how this area was created, specifically in relation to environmental bads. Thank you for illuminating this story!

RM

May 1, 2020 — 6:36 pm

Glad you enjoyed it!