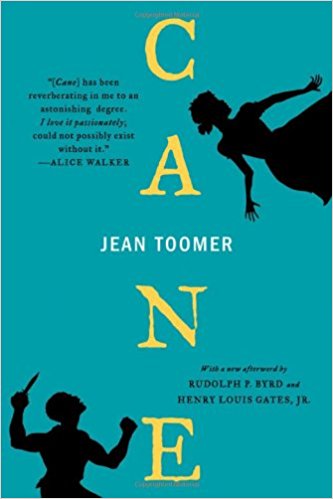

Recently, I have written a post for another academic blog on Jean Toomer’s Cane, a novel set in Georgia and the south on the suffering of black community similar to Toni Morrison’s Beloved. The book is written in a blend of prose, poetry, and rhetoric that makes it difficult to categorize by genre. In two sections, it covers multiples stories alongside poems that respond to the images and themes that are contained within them. Some of the most powerful moments of the book such as “Esther”, the story a storekeeper who is fascinated by a black man who returns to her town not as impressive as she once thought. A two-page story, “Rhobert”, also caught my eye as a fascinating image of a run-down, black home in the south. I also liked several poems in the book, including “Song of the Son”, “Reapers”, and “Harvest Song”. In my initial blog post, I connected several themes of the end and death to apocalypse, in that the poem’s images of darkness, death, and ends. But these were shallow close-readings of the images. I titled the piece “The Gentle Apocalypse”. But it is not always gentle. One story, “Blood Burning Moon”, confused me as it was a strikingly violent story of lynching that stuck-out next to my examples. This example was not the exception. My idea of the “gentle apocalypse” was the exception. I addressed Toomer’s use of female objectification, violence, and brutality in the south toward the end, but I am troubled as to how well I accomplished that. The goal of this re-reading of both the post and Cane is to pinpoint where I could improve the accuracy in my analytical writing.

Some aspects of the blog post had commendable aspects, despite several notes it could have addressed several errors in my writing or expanded my argument. It was a good thought to lead with a definition of apocalypse inspired by Susan Bower’s “Beloved and the New Apocalypse”. Apocalypse is looking into the boundary or edge of one realm to another, while observing both and anticipating change. Despite my definition being worded quite differently, I realized I should have cited her and explained the quote in more detail. In editing the post, I have added the citation for ethical reasons. I realized this post, while confined to only 250 words, had become blatantly “1-on-10” as Writing Analytically would put it (WA, 207). I mention images in Cane like, “dusk and night” at first, but forget to mention locations of this conversation such as in the poem “Song of the Son” (Toomer, 17). The poem literally addresses, “for though the sun is setting on / A song-lit race of slaves, it has not set;” among other lines that compare the dawn and dusk to an eternal memory of slavery. The example of the story “Esther” in Cane could have gone farther. While it stated Esther changed her, “perspective of the town possibly because she lost her reason to stay”, I failed to acknowledge that this was in reference to a scene where a girl was disgusted to have almost slept with Barlo, a man many years his senior. There needs to be more discussion of how Esther was humiliated into changing her perspective of the town, that her reason to stay was lost due to becoming an object of sexual objectification. Finally, I needed to wrap together how these images of departure, of violence, and of time passing in dusk and dawn, culminates to this definition of apocalypse. This conclusion would further ask how Toomer imagines the future of the South. Any blog post could be tighter and more composed if it recognizes it’s key point or definition and concludes by bringing it to a new stage of questions. Which is what I am about to do right now:

Toomer once called Cane a “swan-song of the South” after observing how the black folk spirit of the south fading with the Great Migration. Can Morrison’s Beloved be seen as a text which can converse with Toomer on Slavery? Is this apocalypse of the south also a Slave apocalypse, a South apocalypse. Or both? I favor both as an answer, but I wonder if the two apocalypses should be considered separate epochs.

As for my original blog post, how do you think I did with my self-study? Visit the link and let me know what you think.

Works cited:

Bowers, Susan. “Beloved and the New Apocalypse.” Critical Studies in Black Life and Culture, Toni Morrison’s Fiction Contemporary Criticism, Garland Publishing, 1997, pp. 209-228.

Toomer, Jean, and Rudolph P. Byrd. Cane: Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism. W.W. Norton & Co, 2011.

I agree that “Cane” echoes the apocalypse notion in “Beloved” especially in the context of slavery. It also seems that violence may not be the main factor or trigger of an apocalypse but rather a residue of the coming of change. As you mentioned, Esther is objectified as a sexual woman because she willingly decides to give herself to Barlo until she comes to her own conclusions against it. However, the need to change the fact that she is objectified as a woman, or even the fact that she is objectified, can bring about the need for change and/or violence that will subsequently bring about the apocalypse. As we saw in “Blood Burning Moon,” it was the yearning for and objectification of a woman that lead to violence and the apocalypse.

If you don’t mind, I’d like to engage with the substance of the post rather than the self-study.

The idea of the “gentle apocalypse” is interesting and I see how considering slavery as a form of apocalypse could inform your understanding of both slavery and apocalypse, however, I’m not sure exactly what about apocalyptic literature you’re analyzing and what idea you want to try to advance. What do you think apocalyptic literature is an expression of? What does the use of an apocalyptic event signify from a sort of sociological perspective?

I think you’ll have to lay out what A: what counts as an apocalypse for you and B: the specific modes of the in-fiction existence of an apocalypse that you’ll consider at the start of your paper (the narrative could take place before, after, or during an apocalyptic event or it could merely allegorically allude to an apocalypse; constitute a microcosmic apocalypse — as in the slavery example; contain references to an in-fiction-fictional apocalypse; or relate, allude to, or in some way contain an apocalypse in myriad other ways). The range of what could be considered “apocalyptic literature” is astronomical so you’ll have to tighten your scope and/or use just a few examples to establish a trend within a genre that you define in order to avoid making statements about books/movies/short stories that you aren’t even aware of.