Memorial Park Home | History | Lincoln Cemetery | From Cemetery to Park | Railroad Station | Community Voices | Cemeteries as Sites of Discrimination | Photo Gallery | Historical Resources

Community Voices

by Claire Jordy & Gibson Holland

There is a substantial dearth in the amount of reporting conducted on the Lincoln Cemetery’s conversion into James Young Memorial Park. Outside of the a few Borough of Carlisle Minutes from September, 1971 and a couple pieces from the same year in The Evening Sentinel, there is little information about the park’s transformation.[1]

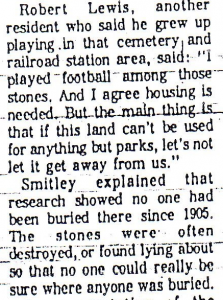

The information available pertains to the debate over the park, though not in the manner one might expect. While still in the planning stages, residents protested turning the Lincoln Cemetery into James Young Memorial Park because some felt the land could have been better used as a site for housing. The debate had little to do with the park’s historical significance.[2]

After the initial debate on how to re-purpose the land, the cemetery/park received no attention from local news sources. At its completion in April, 1973, the James Young Memorial Park received no coverage from local news sources. The Evening Sentinel contained nothing about the opening or any references to a debate about the removal of headstones – generally a very controversial and frowned upon act.

As it stands, there is more information available about the men interred at Lincoln Cemetery than those who pushed for the creation of James Young Memorial Park. This is largely due to the abundance of primary documents available concerning Memorial Park throughout its history. The House Divided Project has collected a lot of primary documents about the Lincoln Cemetery and the people buried there.

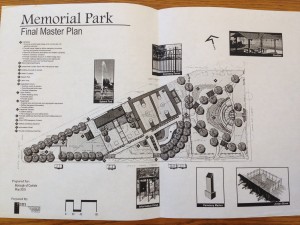

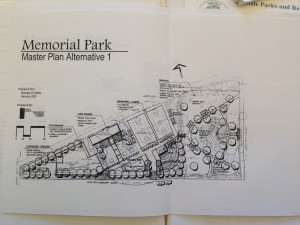

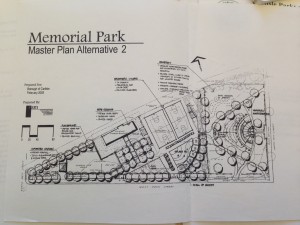

During the conception, development, and renovation of Memorial Park, there were many opportunities for community input on the park and use of the space. When the park was being converted from a cemetery and railroad station to a public park, local Carlislian Rev. Robert Bailey said he would rather the degraded cemetery be converted into affordable housing.[3] There was more evidence of community input during the substantial renovation of Memorial Park during 2002-2003. YSM Inc. created three major renovation plans for the park and proposed them to the community over several months (January 2003-June 2003).[4]

News articles from around this time advertised the opportunities for citizens to express their opinion about park renovations. The community demands that resulted from these meetings include: more shade and less blacktop, more lighting, ban of pitbulls, addition of cross walks on Pitt Street for safety, update of some play equipment, addition of amphitheater for concerts, consecration of Lincoln Cemetery through removal of tables, addition of trees and walkway, and the fencing off from the rest of the park.[5] Subsequent plans by YSM Inc, and therefore the current Memorial Park, reflect these changes.[6] Not to forget, the initial renovation of Memorial Park in 2003 was driven by community support for updating of the park and cemetery to match the recently updated railroad (Hope) station. James Washington was the main proponent, acquiring a substantial state grant for the specific action of consecrating Lincoln Cemetery.[7]

In the past five years, there has been a spike in the interest about the Park’s history. Between Dickinson College’s House Divided Project and the Carlisle West Side Neighbors, the history of Lincoln Cemetery has been well documented. Both the House Divided Project, started by Professor Matthew Pinsker, and the Carlisle West Side Neighbors investigated the Lincoln Cemetery because of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.[8] The park is a telling piece of American history, not simply because of all of the information discovered about the African American Soldiers buried there – but because of the land’s changing purpose and format over the years. It is very American in many ways for a marginalized group’s history to be lost for years and slowly revived by a few engaged community members who, in the case of Memorial Park, were James Washington, Dickinson students and professors, and the Carlisle West Side Neighbors.

[1] “Plans for Park Protested.” Evening Sentinel. November 8, 1971. [2] “Plans for Park Protested.” Evening Sentinel. November 8, 1971. [3] “Plans for Park Protested.” Evening Sentinel. November 8, 1971. [4] YSM Inc plans – Oct 2, 2002; May 2003; June 2003; Found at the Carlisle Department of Parks and Recreations [5] Blymire, David. “Residents give views on park.” January 31, 2003. The Sentinel.Miller, Dan. “Park’s future in planning.” January 31, 2003. Patriot News.

Found at Carlisle Department of Parks and Recreations.

[6] YSM Plans, found at Carlisle Department of Parks and Recreations. [7] “Policy Briefing Summary, Section IV. Financial Impact on Budget.” Found at Carlisle Department of Parks and Recreations [8] http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/