By Kayleigh Wright

The 20th century in the United States of America saw considerable progress in human rights. Women gained the right to vote, the Supreme Court declared that separate is not equal in public education, and then there was the passage of various civil rights acts, and the implementation of Title IX of the Education Amendments. Signed in by President Richard Nixon in 1972 [1], Title IX reads, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”[2] This act about the time of the constitutional amendment passed by Congress (though never ratified) reading, “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on the account of sex.”[3] H.W. Brands describes in his book American Dreams the rise of the feminist movement in the 1960s and 70s. Across the U.S., organizations formed that encouraged women to, “leave their kitchens and laundries…until they achieved equal pay, equal respect, and equal rights.”[4] The Implementation of Title IX, although not expressly stating the benefits to women, was another victory for those pushing for women’s rights.

The passage of the Title IX act did not immediately solve all problems for collegiate women. The one area where this act received the most publicity has been in collegiate athletics. The prevailing opinion in the 1970s was still that women were physically inferior to men, especially in sports. John A. Howard wrote to an assistant of President Nixon on the matter of Title IX while serving as president of Rockford College, saying, “there is no way the government can make oranges and apples equal. Nor can the government make men and women equal.”[5] This widespread view, especially common in the collegiate sports world itself, made opposition to Title IX a powerful force. Robert C. James of the NCAA believed that, “imposition of unrealistic administrative and operating requirements, drawn by persons totally unfamiliar with the practical problems of athletic administration, in the name of a non-discriminatory sex policy,” could be considered counterproductive.[6] Some people, such as Jim Kehoe, went so far as to suggest that the women were incompetent to act on the legislature of Title IX, saying, “[the] people who are writing this thing are all women. They have never lived in this world, or worked in this world, yet they’re passing judgment on this world.”[7] NCAA executive Walter Byers worried that “the women writing this thing are terribly naïve about intercollegiate athletics.”[8] Resistance began before the act was officially passed, and continued to surge following its passage. Thus, the implementation and successes of Title IX took a lot more effort than we can appreciate today.

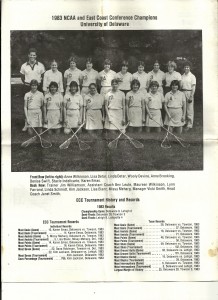

Bev Bruce was a lacrosse player and coach at the University of Delaware when Title IX was in its early stages of implementation. To this day, she can still recall how, not so long ago, equal rights for women were not as simple as just passing a law. She graduated in 1977, and accepted a coaching position at her alma mater in 1980. Looking back on her experiences before Title IX was put into effect, she remembers the unequal treatment she encountered. “The girls were expected to shower and change before getting on the late bus, and the boys just got on in uniform,” she says.[9] She also notes that there were far fewer sports offered for women when compared to men, “there was one sport in the fall: field hockey…two sports in the winter…[in] spring there was lacrosse and that was it.”[10]

Despite Title IX being passed before Bev entered into her undergraduate education, not much seemed to have changed from her high school experience with sports by the time she was involved in collegiate athletics. She remembers attending practices for her lacrosse team at a field that was, “in the way far back…in the middle of nowhere that was always muddy.”[11] “Although we represented the University of Delaware, the students had to assume the costs of [competition] and transportation,” she remembers, “although we had an intercollegiate schedule, we were coached by a graduate student.”[12] Nearly a decade after Title IX was signed in as an amendment, as Bev became a coach, female teams across the country and at the University of Delware were still dealing with some of the issues they faced before the implementation of the act. “We still got the lousiest fields, the field house was by the three-hole golf course that they had… So you’d be playing the game with golf balls whizzing by your head,”[13] she reminisces. When she was playing herself, she remembers having to change in a small side locker room and never having access to the main gym. But the most exciting things she remembers gaining for the team as a coach were material things, not real equality in rights and access. “We were happy to have kilts that weren’t falling apart at the seams, and they all matched, and the numbers were in sequence,”[14] she says.

She also noted the gap in time between the passage of Title IX and actually putting it into practice, saying, “At Delaware, [Title IX] didn’t even kick in, they didn’t start adding teams, until ’79 or ’80. It took them [at least] 5 years to get up to speed.”[15]

The barriers that needed to be deconstructed to see the full impact of Title IX were not able to be resolved simply with legislation. Social stigmas and preconceived stereotypes were the biggest hurdles to be overcome in order to see the successes of the act. In an article for the Washington Post, Patricia E. Barry speaks to how the roles of men and women were perceived as different, saying that men who go to college to play sports go, “to become professional athletes,” while the goal of women is, “to get an education.”[16] A collegiate female athlete Sherri Bleichner, in the same article, calls attention to how she needed more ‘substance’ to get into college, such as good grades, while the boys got in “on their playing ability alone.”[17] The only way that Title IX could have its full beneficial impact was for there to be a societal shift, especially among collegiate athletes, coaches and athletic departments.

Charles L. Crawford, a basketball coach at Queens College, in a 1975 column for the New York Times, importantly noted, “this attitude will not develop overnight.”[18] He wrote that “we must begin thinking of all our institution’s student athletes as members of our program,” and that, “men will have to reevaluate long-held assumptions.”[19] He suggested that, “the coach who maintains the traditional attitude of “natural” male superiority will feel constantly threatened.”[20] Crawford tried to remind fellow male coaches and athletes that success is success whether you play on the nicest field or have the most funding. He suggested that although many were predicting the demise of collegiate athletics under Title IX, “realization of our common human goals and striving for mutual professional respect can produce not only harmony but also more significant achievement for school and collegiate athletics.”[21] Crawford implied that, perhaps it was the long held prejudices and stigmas that will cause destruction in collegiate athletics, not Title IX.[22]

Although Brands does not provide any direct reference to Title IX in his book American Dreams, there is no doubt that the act has had significant bearing on women, specifically in sports. Today, a mere 43 years after the passage of Title IX, women across America play collegiate athletics at all levels. It is now the sport division under the NCAA that determines whether student athletes are eligible for scholarship, not the school itself or the gender. Any athletes playing for NCAA Division I or II schools are eligible for scholarship money for athletics. In some sports, such as basketball, cross-country, ice hockey and swimming, there is equal or more scholarship opportunity available to women.[23] Although it is impossible to ever completely eliminate prejudices and stigmas against women, especially in a notoriously male dominated area such as athletics, Title IX has gone a long way towards legally improving women’s chances for opportunity and success. Bev Bruce reflects on the impact of Title IX, saying, “I think that it’s so wonderful to see young women like you, or a couple of the teachers at school [where I work] that have recently graduated…who have really played hard, played competitively, and had all those opportunities that we didn’t have. I think it’s just fabulous. But the unfortunate side is, and maybe this is why it all changed, that it had to be legislated. It took legal action to hold people to equal opportunity for women.” [24] So in society, in the eyes of the American population, will men and women ever be truly equal? Perhaps not. But those who fight and succeed in getting America closer to inherent inequality for the genders see success every day from Title IX.

Footnotes:

[1] Title IX.,”The Living Law,” (2015). http://www.titleix.info/history/the-living-law.aspx

[2] United States Department of Labor “Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972,” (2015).http://www.dol.gov/oasam/regs/statutes/titleix.htm

[3] W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: The Penguin Group, 2010), 177-78.

[4] Brands, 177.

[5] Ying Wushanley, Playing Nice and Losing: The Struggle for Control of Intercollegiate Women’s Athletics 1960-2000, (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2004), 83. https://books.google.com/books?id=XzDu0PLXVy4C&pg=PA82&lpg=PA82&dq=implementation+of+title+ix+in+the+1970s&source=bl&ots=eLWsim3Cuv&sig=zl00klrskya6D_qzsYvym2TLwYs&hl=en&sa=X&ei=oRZAVbOBA8OWNs23gNgE&ved=0CEkQ6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=implementation%20of%20title%20ix%20in%20the%201970s&f=false

[6] Wushanley, 83.

[7] “Title IX: Taking the Macho out of College Sports.” The Boston Globe, 23 March 1975,1. [ProQuest].

[8] “Title IX: Taking the Macho out of College Sports,” 1.

[9] Phone Interview with Beverly (Bev) Bruce, Carlisle PA and Scituate MA, March 20, 2015.

[10] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[11] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[12] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[13] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[14] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[15] Bev Bruce, Interview.

[16] Gary Davidson, “Title IX Begins Changing the Scholarship Outlook for Women.” The Washington Post, 2 February 1978. [ProQuest]

[17] Davidson, 1.

[18] Charles L. Crawford, “Title IX: No Reason For Fright.” The New York Times, 10 August 1975.

[19] Crawford, 1.

[20] Crawford, 1.

[21] Crawford, 1.

[22] Crawford, 1.

[23] Scholarship Stats, “College Athletic Scholarship Limits,” (2014). http://www.scholarshipstats.com/ncaalimits.html

[24] Bev Bruce, Interview.

Matthew Pinsker

Received, thanks