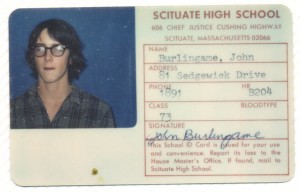

By Isabel Burlingame

Jack Burlingame attended the May 9, 1970 Vietnam War protest in Washington D.C. “I traveled from Massachusetts to Washington D.C. on a chartered bus with other high school and college students,” he remembers. “I and my friends were probably the youngest people on the bus – 15 years old at the time….we had been encouraged by our history teacher to attend.”[1] In 1970, Nixon widened the war into Laos and Cambodia in order to reinforce the image of American interest in Southeast Asia after withdrawing from parts of South Vietnam. According to H.W. Brands in his book American Dreams, “Whether or not these efforts conveyed to the communists the message Nixon intended, they got the attention of the antiwar movement in America. The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war.”[2] The protests to which Brands refers took place largely on college campuses, but also included those in major cities where people from all demographics of the population, such as 15-year-old Burlingame, spoke out against the Vietnam War. Both Brands and Burlingame agree that the protests had an important role in influencing the government to end the war, but neither seem to discern any lasting impact beyond that. Despite the influence that the protests had on the American government at the time and their immense prevalence across the country (with some ending in tragedies such as the Kent State shootings), their effect did not last beyond the immediate context of the war.

The Vietnam War protest movement began long before Burlingame attended the 1970 protest in Washington D.C. The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), led by Tom Hayden, was one of the first antiwar groups to emerge around 1960. Their efforts did not have a noticeable impact for the first five years.[3] In 1965, however, President Lyndon Johnson expanded America’s involvement in the war by increasing troops and funding, which “caused membership [of the SDS] to mushroom”.[4] The SDS subsequently split into moderate and radical factions, the latter of which sometimes turned to violent protest tactics such as bombings.[5] The mid to late 1960s also saw the beginnings of the peaceful protest movement. Marches in major cities, such as the one in D.C. that Burlingame would attend a few years later, grew in numbers and included a wide variety of Americans, ranging from students to hippies to white-collar businessmen.[6] While some viewed the protests to be successful, they did little to change the direction of the war as controlled by the government. According to Brands, “Ronald Reagan, then running for California governor, dismissed the antiwar protests in three words– ‘sex, drugs, and treason'”[7] The protests allowed the portion of the population that opposed the war to express their views, but their effect on the rest of the country and much of the government was unclear. However, both Brands and Burlingame contend that the protests had a cumulative effect that swayed the government’s decisions. Brands references Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts, who was one of the first House leaders to change his position on the war.[8] Burlingame pointed out that “as public sentiment inexorably tilted against the war, politicians were acutely aware of the shift and its potential implications at the ballot box.”[9] As the protest movement increased, those running for office were forced to consider the views of the protesters.

By May of 1970, the protest movement had grown considerably. On and around May 9, protests occurred in major cities and on college campuses across the country, including the march in Washington D.C. that Burlingame attended. Burlingame remembers a sense of camaraderie among the protesters, all working towards a common goal, although with a variety of motivations. Many of the protesters had been angered by Nixon’s covert invasion of Cambodia, and others by the Kent State shootings, which had occurred less than a week before. Burlingame cites both of these events as reasons for his participation in the protests, as well as “the expansion of the draft with the elimination of several categories of deferments, including those for college students. The fact that I was just a few years from my 18th birthday and eligibility for the draft certainly captured my attention and heightened my awareness of the war and its consequences.”[10] The draft policies had changed two years earlier, in 1968. Previously, students attending graduate school or planning to attend the next year were exempt from the draft, as were those in certain occupations. Removing these exemptions increased those eligible for the draft by roughly 430,000. This decision led to a surge in the protest movement, drawing in educators who contended that many bright young minds that were essential to the country’s future would be needlessly lost in the war.[11] Even high school students like Burlingame feared the effect that the new policy would have on them and joined the movement.

There is little doubt, however, that the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970 dramatically increased participation. Burlingame recalls the May 9 march in D.C. having been planned before the shooting, but “the massacre undoubtedly led to an increase in the number of students taking part.”[12] In a front-page New York Times article the day after the shootings, President Nixon was quoted as urging protesters towards “peaceful dissent and just as strongly against the resort to violence as a means of such expression.”[13] Burlingame recalls the protest that he attended as reflecting this wish for peace. “Despite Kent State, I experienced no feeling of impending violence or fear that a riot might break out.”[14]

American involvement in the Vietnam War came to an end in January of 1973 when Henry Kissinger bargained the withdrawal of US troops for Le Duc Tho’s agreement to a ceasefire.[15] Two years later, in 1975, once American troops had been withdrawn, North Vietnam launched a successful attack and captured South Vietnam, bringing the entire country into communist rule.[16] The United States had essentially failed in its attempt to keep communism out of South Vietnam, wasting years and thousands of lives in the process. Burlingame believes that the protests did ultimately decrease the duration of the war, and speculates that “without them, the war would have dragged on several years longer and resulted in significantly more casualties and destruction.”[17]

Perhaps the protests were successful in their immediate goal: bringing about the end of the Vietnam War. But neither the protests nor the Vietnam War itself left a prominent legacy on the United States, judging by American involvement in future conflicts such as the First Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War. As Burlingame eloquently puts it, “I struggle to discern any lasting impact from the Vietnam War protests, other than to give aging hippies something to reminisce about…In the years since, the U.S. has experienced no shortage of legal and illegal wars, covert actions, extraordinary renditions, illegal arms sales, state-sponsored torture, POW abuses, both ‘collateral’ and criminal killings of civilians in war zones, imprisonment without trial, military profiteering, drone strikes of dubious legality and morality, and other deplorable acts carried out in our name using our tax dollars. Would the rogue actions of the U.S. over the last 40 year have been even worse if the Vietnam protests had never happened? Perhaps, although it’s hard to imagine.”[18]

[1] Email Interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[3] Ibid, 153.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 154.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, 155.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, April 30, 2015.

[10] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

[11] “Resist Or Fight!” Bay State Banner, Feb 22, 1968 [ProQuest].

[12] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

[13] John Kifner, “4 Kent State Students Killed by Troops: 8 Hurt as Shooting Follows Reported Sniping at Rally 4 Kent State Students, 2 of Them Girls, Killed by Guardsmen.” New York Times, 5 May 1970, 1.

[14] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

[15] Brands, 174.

[16] Ibid, 175.

[17] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

[18] Email interview with Jack Burlingame, March 23, 2015.

Leave a Reply