By: Max Menkes

Stephen Menkes was a 9-year-old boy when World War II ended in 1945. He had spent most of his early years being raised by his grandmother while living in her small apartment with his parents and his Uncle Joe. As the fear of war subsided a whole new era began, the Post War Baby Boom. As H.W Brands writes, “After World War II the combination of more time, more resources, and more kids created a child-based culture unlike anything previous in American History…But they grew up with a sense of entitlement, a feeling that the world existed for their benefit.” [1] Stephen would probably agree as he recalls, “I remember vividly the day my dad loaded my mom and me in our brand new black Packard and drove us out to Atlantic Beach on Long Island to show us our new house. I was so excited to discover that I would have my own room and a huge backyard. It got even better when I learned that my mom was quitting her job to stay home and that she was pregnant.” [2] It would be a whole new way of life for Stephen, “my dad commuted to the city each day to go to work but he spent most nights and every weekend at home. We had barbecues in the backyard and block parties with friends and neighbors.” [3] Long gone were the days of pinching pennies, eating cabbage soup, sleeping on a cot in the living room, collecting fat for the war effort and preparing bomb shelters. The post war baby boom was a new beginning for the nation. “They would grow up more confident and secure with who they were and what their future would hold. They had no worries, no money problems and no war!” [4] The Post World War II Baby Boom gave birth to a society comforted by a more focused family life and homogeneous suburbs and raised to believe that the world was theirs for the taking.

As a child of the Great Depression Stephen lived through both emotional and physical changes that affected his family life. “A worldwide depression struck countries with market economies at the end of the 1920s. Although the Great Depression was relatively mild in some countries, it was severe in others, particularly in the United States, where, at its nadir in 1933, 25 percent of all workers and 37 percent of all non farm workers were completely out of work. Some people starved; many others lost their farms and homes.” [5]

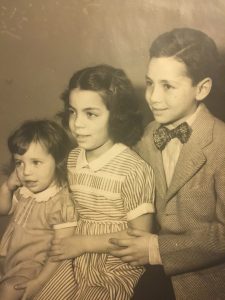

Money was tight so Stephen’s mother was forced to find a job to help support the family. Since his mother went back to work as a secretary and money was tight his family was forced to move into his grandmother’s two bedroom apartment over a bakery in the Lower East Side of New York with his Uncle Joe. He candidly admits, “At first I was excited at the idea of living with my grandmother since I had grown accustomed to her amazing Friday night dinners that included homemade Rocky Road candy but I soon discovered that all that was a thing of the past.” [6] The living space was so crammed; he slept on a cot in the living room and as a young boy he remembers, “Playing stick ball in the street with my friends until the sun went down because none of us wanted to go home to our cramped apartments and cabbage soup dinners.” [7] Things got worse as the war started and demanded more of his family. He barely saw his parents that worked all day and then volunteered for the Civil Air Patrol in the evenings. His parents now committed to helping the war effort after work and he rarely spent time with them. Even as a young boy he realized the significance of contributing to the protection of his family and his country and he states that “ I remember my mom and grandmother collecting fat and putting it in coffee cans and then I had the proud job of bringing it to the District Office. I felt very proud and grown up that I could do something to help the war effort.” [8] President Franklin Roosevelt helped create the significance of the war effort in his Third Inauguration speech on January 20, 1941, “Democracy alone, of all forms of government, enlists the full force of men’s enlightened will… It is the most humane, the most advanced, and, in the end, the most unconquerable of all forms of human society. The democratic aspiration is now mere recent phase of human history… We… would rather die on our feet than live on our knees.” [9] The war occupied the nation’s thoughts and their activities. Stephen and his family lived in fear of sirens going off warning of bombs. Then to make things worse his Uncle Joe enlisted and the family now had to rely on one less income and live with the new fear of losing a loved one to the war.

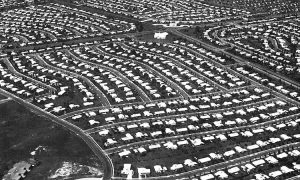

In 1945 as the war came to an end, a new car and a move out to the suburbs would be the start of a whole new life for Stephen and the beginning of a new era for the country. The move to family centered neighborhoods was not easy, “In the years after World War II, however, not everyone could attain that promised tranquility. One problem was a severe housing shortage. A combination of unusually high birth rates (which bred the baby boomer generation) and plummeting construction left many families struggling to find any suitable shelters, sometimes living in boxcars, chicken coops and large ice boxes. To many of those families, the Levittown’s in Long Island, New Jersey and Pennsylvania were the answer to their prayers.” [10]

The house provided a new spacious way of life and the new car provided a way for his father to spend more time with him and just commute to the city for his job. H.W Brands writes the new way of life was partially due to, “the eight-hour day and forty-hour week that became a standard during the Depression, partly as a way of rationing the available work.” [11] Family life for Stephen changed for the better and his younger sisters benefited from this new way of life, “my parents were very active in my sister’s lives and attended recitals and school functions. They each had their own room and they were constantly bringing friends over to the house for dinner and parties. Our house was filled with laughter and good food not like the somber home of my grandmother. They didn’t know how sick you get of eating cabbage soup or how it feels to sleep in the living room.” [12]

The move to the suburbs provided a sense of community and a much needed sense of safety that deeply affected family life. Since the families no longer feared sirens Stephen and his sisters were allowed to stay out late and walk into town, a new freedom that he cherished. But it wasn’t just the fact that the war was over, the suburbs provided a sense of community that gave them a needed sense of security. Stephen remembers fondly that, “We all knew one another, my dad worked in the city with the other dads, I went to the same school as my friends, and my mom was surrounded by her friends. Everyone had common interests which seemed to provide a sense of safety that was important after the war.” [13] William Levitt believed that nothing was wrong with the homogenous suburbs he created, “The plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities. This attitude may be wrong morally, and some day it may change. I hope it will. But as matters now stand, it is unfair to charge an individual with the blame for creating this attitude or saddle him with the sole responsibility for correcting it.” [14] This sense of safety that came from common interests and backgrounds was later looked at as discrimination but for my grandfather Stephen Menkes it was no different than living in the city, “I guess it wasn’t a very economically or racially diverse neighborhood but most people didn’t care about that back then. In the city we had neighborhoods for Jews and others for Italians so living with people that were similar was nothing new.” [15]

The increase in the family’s disposable income after the war also changed the family dynamic. The purchase of a television was one of the factors that contributed to this shift. The family dinner was an important part of family life but the time in front of the television also became a new family activity. The dinner table provided a formal time for the family to discuss their day but even that was different after the war, “ When I was younger my dad did most of the talking and conversations were more solemn but when we moved out to the suburbs my mom definitely had more to say. I think working had given her the confidence to feel like she could contribute something more to the conversation.” [16] The television was a source of information for those conversations, “My mom would always tell us about the latest and greatest soap or new product that she saw on TV that would somehow greatly improve our lives!” [17] Stephen admits that, “his conversation at the dinner table was more about his class work and hearing that with good grades the world was his for the taking.” [18] After dinner the family now gathered in the living room and bonded over shows on television. Stephen laughs as he remembers that it wasn’t just the shows but the close proximity to each other and to the television that brought them closer, “We all sat close to the television because it wasn’t as big as the ones we have today and it was black and white!” [19] The shows were mainly family shows that enhanced the quality of family life. Stephen shared that his favorite show was Howdy Doody which he watched every afternoon but says that as a family he remembers watching the Milton Berle variety show in the evening. Stephen is quick to confess that the TV commercials were just as important as the TV shows, “We all got our cues as to what was the latest and greatest from TV” [20] and that was definitely the intent of those commercials. The new purchasing power that existed and the new idea that the purchaser deserved those purchases, especially after years of war and financial difficulties, was a boom for advertisers. Stephen remembers his favorite commercial was the one for Bosco chocolate syrup, “my friends and I wanted it on everything after we saw the commercial and the chocolate egg cream soda became my favorite, and still is.” [21]

The family car also contributed to a change in family life. The car provided a way for his father to commute to the city and come home to a house and family with a better quality of life than what they had previously had in the small apartment in the city, “Postwar Affluence redefined the American Dream. Gone was the poverty borne of the Great Depression, and the years of wartime sacrifice were over. Automobiles once again rolled off the assembly lines of the Big Three: Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler. The Interstate Highway Act authorized the construction of thousands of miles of high-speed roads that made living farther from work a possibility.” [22]

A road trip now provided a new form of family entertainment that brought the family closer together. Family time was valued as Stephen looks back, “I remember the long car trip to Florida but it was a family adventure that became a family tradition. We took more car trips to visit relatives or go up to the country for the weekend and my world got bigger” [23] The baby boom was not just a boom in the number of children being born but a boom in the quality of family life that gave children the sense that they could do anything and go anywhere.

The Post War Baby Boom was a welcome reprieve from the dark days of war and it created a confident and self-assured new way of life. “Almost exactly nine months after World War II ended, “the cry of the baby was heard across the land,” as historian Landon Jones later described the trend. More babies were born in 1946 than ever before: 3.4 million, 20 percent more than in 1945. This was the beginning of the so-called “baby boom.” In 1947, another 3.8 million babies were born; 3.9 million were born in 1952; and more than 4 million were born every year from 1954 until 1964, when the boom finally tapered off. By then, there were 76.4 million “baby boomers” in the United States. They made up almost 40 percent of the nation’s population.” [24]

The new generation of baby boomers had never experienced poverty or war. They were born post-depression, after incomes had increased, and during a time after the war when opportunities for spending were at a new high for several reasons. Firstly, production lines and factories that had been directed to produce products necessary for war were once again producing cars and televisions. Secondly the new commercials on televisions were targeting the parents with new disposable income and tapping into their desire to give their children what they had done without. Thirdly the man power for assembly lines returned to the normal strength as men returned from war. As Stephen Menkes describes the baby boom era allowed his younger sisters to be raised by their mother who was able to return home from the workforce and concentrate on improving the life of her family. The new quality and quantity of time spent with family and community led to a confident and secure environment which for him was a positive not a negative. As H.W Brands writes, “parents and grandparents wanted their children to have what they had been compelled to do without.” [25] So while Stephen boldly admits to agreeing with H.W. Brands characterization of the generation as one with “a sense of entitlement” he proudly confesses, “they were spoiled but even I enjoyed spoiling them. There was a ten-year difference between me and my sisters so I am just as guilty as my parents of trying to make sure that they had everything they ever wanted.” [26] The new attitude associated with the Baby Boom propelled the nation into a time of prosperity through increased spending and created an attitude that they deserved everything that the world had to offer. This sense of entitlement could be why the nation grew to consider itself a leader among nations with an air of superiority but could also have been the reason that our nation is in debt today. The baby boom generation that was coddled by their parents and brought up to believe that they deserved to have it all was a symptom of the previous generation suffering through a financial crises and war. Stephen’s experiences describe that this was a natural and protective response and not one intended to harm others. In fact, the new sense of love and security that was a byproduct of larger families with greater resources greatly influenced Stephen in becoming an OBGYN with a specialty in infertility, “I chose to become an OBGYN so that I could help bring that same feeling to all families.” The more focused family life, child centered environment, and homogeneous suburbs allowed Stephen to reach for the stars and go from sleeping on a cot in the living room to providing a much needed service that would bring forth a new generation.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p.70

[2] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[3] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[4] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[5] Smiley, Gene. Rethinking the Great Depression: A New View of Its Causes and Consequences. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002.

[6] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[7] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[8] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[9] Quoted in Second world war history, President Franklin Roosevelt (secondworldwarhistory.com, 2003-2017)

[10] Galyean, Crystal. “Levittown.” US History Scene. 10 Apr. 2015. Web. 8 Nov. 2017.

[11] H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p.70

[12] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

[13] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[14] Kyle Sabo, “The Levittown Legacy: Segregation in Suburbia?” Newsday, September 2, 1957

[15] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[16] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[17] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[18] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[19] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[20] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[21] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[22] ushistory.org. Suburban Growth. U.S. History Online Textbook, 2017

[23] Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

[24] History.com Staff. Baby Boomers. A+E Networks, 2010

[25] H.W. Brands, American Dreams p.70

[26] Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, November 10, 2017

Second Interview with Dr. Stephen Menkes, December 5, 2017

- How did you like moving out to the suburbs and who lived there?

Answer: I loved living where we could all get together in backyards instead of just playing on the street or in the park. My parents let us stay out late because they no longer feared sirens going off and having to worry where I was. My sisters never had that fear of trying to get home because you were afraid a bomb was going to get dropped. My friends and my parent’s friends all lived close to us. We all knew one another, my dad worked in the city with the other dads, I went to school with my friends and my mom was surrounded with her friends. Everyone had common interests which seemed to provide a sense of safety that was important after the war! I guess it wasn’t a very economically or racially diverse neighborhood but most people didn’t care about that back then. In the city we had neighborhoods for Jews and others for Italians so living with people that were similar was nothing new.

- Did you eat dinner at a table or did you eat in front of the television?

Answer: We always waited for my dad to get home from work and we always sat at the kitchen table. It was a little more formal then today. I helped my mom set the table and we had conversations at the table and then we all moved to the couch to watch a show.

- What did you discuss at dinner?

Answer: We usually waited to see my dad’s mood and then conversations went from there. When I was younger my dad did most of the talking and conversations were more solemn but when we moved out of the city after the war my mom definitely had more to say. I think working had given her the confidence to feel like she could contribute something to the conversation. My mom would always tell him about what the latest and greatest soap or new baking product that she and her friends were now using and how it would greatly improve all our lives!! I usually discussed my classes and was always reminded of how my academic success was the key to my future.

- What kind of shows did you watch?

Answer: I loved Howdy Doody and at night I remember watching Milton Berle, which was a variety show. We always sat together probably because we only had one TV but all the shows seemed like family shows anyway. We sat close to the TV because it wasn’t as big as the ones we have today and it was black and white!! The commercials on TV were just as much fun as the TV shows. We all got our cues as to what was the latest and greatest from TV. I remember the Bosco commercial for chocolate syrup! My friends and I wanted it on everything after we saw the commercials and chocolate egg creams sodas became a favorite!! Commercials were definitely product driven and designed to make us feel like we deserved to have the best so why not shop and get them.

- How else do you think your life changed after you moved out of the city?

Answer: We were all together more and we planned family activities more. We always had backyard barbecues at someone’s house but we also had more things that just my family did together. Family vacations were new to me. I remember the long car trip to Florida but it was a family adventure that became a family tradition. We took more trips in the car to visit relatives or go up to the country for the weekend and my world became a lot bigger.

Leave a Reply