This week, I planned to focus on understanding more on Jim Powell and Sam Watts because I did not have much information on them.

I began by going to the Dickinson College Archives to inquire about treasurer files relating to employees. They were unable to find treasurer files from the 19th century, so they gave me faculty minutes instead. Unfortunately, but predictably, there was nothing in the faculty minutes that was even semi-related. I also asked if there were any files relating to Powell, Watts, or custodians in general beside the sources already in the drop file. This search also led to a dead end. Because I remembered seeing the “Corps of Hygiene” that provided information and pictures of the black custodians from the 1870s in a copy of the Microcosm, I decided to leaf through a few of the earlier Microcosm’s that have not yet been digitized. While I could not find anything similar to the “Corps of Hygiene,” I did find an interesting page relating to the

Faculty page that lists Spradley and Young as professors in the 1882 Microcosm. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

janitors in an 1882 Microcosm. Listed on the second page of the “Faculty” section, are “Henry Spradley, J. A. N., Adjunct Professor of Experimental Physics,” “Rev. Robert Young, A. M. E. C., Adjunct Professor in Dutch Scientific Course,” and their “Assistants” in West College (Shirley, Kurnel, and John) and East College (Bud, Bob, and Charlie). This most likely satirical piece may reveal six additional black janitors (the three from East College and the three from West College) to further research.

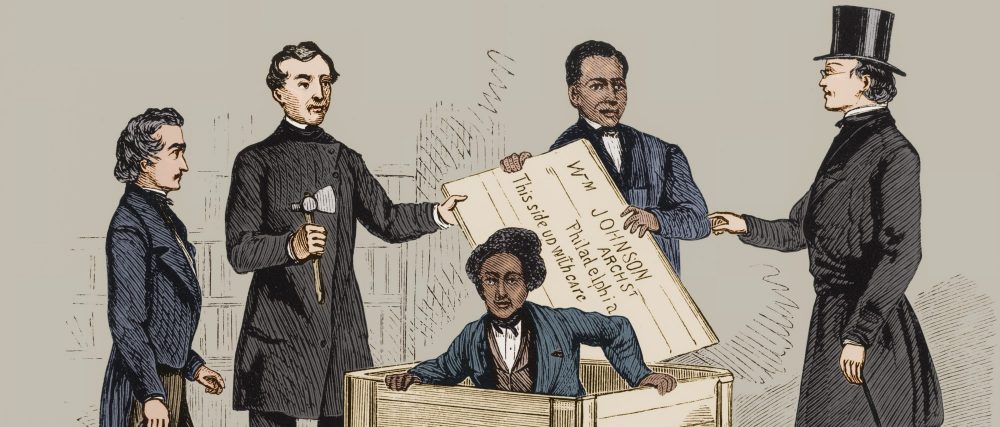

Drawing of “the Janitor” found in the 1881 Minutal. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

Next, I went to the Cumberland County Historical Archives to search through Newspapers.com for references to Powell and Watts. Based on previous research and information from Professor Pinsker, I searched “Banty Jim,” “Jim Powell,” “James Powell,” “Pompey Jim,” “Sam Watts,” and Samuel Watts.” Using Watts’s search names, I only found a handful of articles that related to him. I also only found one article on Powell that I had not seen before. I then tried searching “Dickinson custodian(s),” “Dickinson janitor(s),” and “Dickinson employee(s).” Each of these searches came back with no results. Newspapers.com does not allow advanced searches, so I could not search for “Dickinson” and “custodian,” which may have yielded some results.

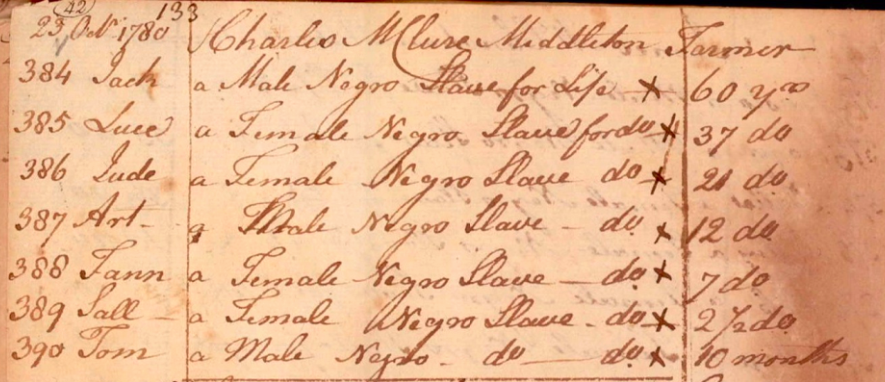

I finished my research for the week at the Dickinson College Archives. I asked for information regarding either Watts or Powell and received a bound thesis written by John Alosi called Shadow of Freedom: Slavery in Post-Revolutionary Cumberland County, 1780-1810. The front cover has a picture

Cover of Alosi’s thesis featuring image of Powell. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

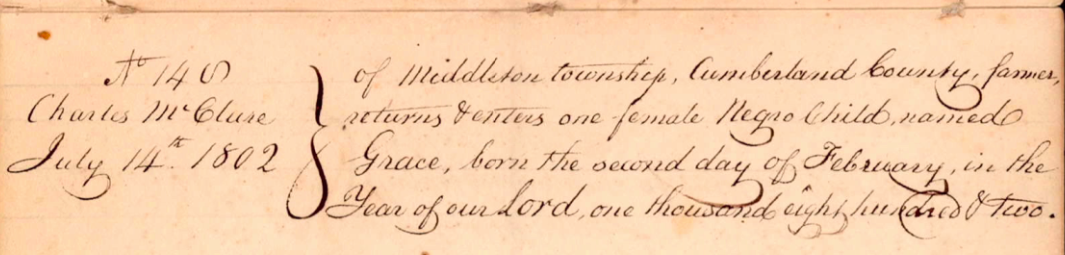

of Jim Powell, and a brief background of him appears in “On the Cover,” a page-long chapter that appears at the beginning of the thesis. The information in this chapter comes from the 1840 census. I also looked for references to slaves, former slaves, and slavery in the card catalogue, and with the help of an archivist, found a few letters by and to various members of the

Page about Powell from Alosi’s thesis. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

Dickinson community regarding their position on slavery from Antebellum to Reconstruction Era. These letters, mostly concerning Dickinson presidents, should be able to provide a basic background on Dickinson’s ties to anti-slavery and pro-slavery, which will be helpful for my Dickinson and Carlisle background page. Finally, I searched through the presidents’ files and pulled documents that seemed like they might be related to black janitors/employees

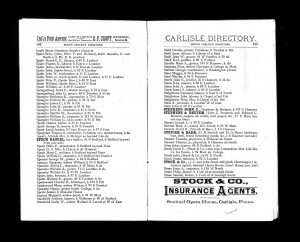

Letter insisting on the firing of the janitor. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

at Dickinson. Here, I found a few letters that will also help to give background to Dickinson’s ties to slavery (particularly relating to the McClintock Riot). However, I found a letter from President W. Neill to the Dickinson College Trustees on September 28, 1826 to insist upon the removal of the janitor because he “has become so very negligent of his duty.” This letter may provide insight into when former slaves or free black men began serving as janitor at the college. It also may prove that the employment of black janitors began at least 16 years before the 1842 letter regarding the employment of former slaves was written to Robert Emory.

While I did not find much more on Powell and Watts than I already had, I found a few interesting sources to humanize them, a few more potential names to add to the list of black janitors at Dickinson College, and background information on Dickinson’s complicated relationship with slavery.