After completing cursory searches on google and discovering Spahr’s recollections of Noah Pinkney, I continued my research by going to the Dickinson College Archives. I began by searching the card catalog but was unable to find anything relating to Noah Pinkney, Henry Spradley, Jim Powell, Samuel Water, Odd Fellows, or even Spahr.

Letter to Robert Emory on September 23, 1842 against the employment of African Americans at Dickinson College. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

I then began looking through the card catalog for Dickinson College presidents’ records after Cooper Wingert discovered a letter written to the college’s president in 1842 regarding the employment of African Americans. This means that African Americans were employed at Dickinson as early, if not earlier than, 1842. Unfortunately, this cursory search into presidential files did not result in anything relating to former slaves who were employed.

I then specifically asked the archivists if they had any files on these four former slaves. While there was nothing on Jim Powell or Samuel Water, there was a drop file on Noah Pinkney, a file of images of Pinkney, a front page of The Dickinsonian with the news coverage on Henry Spradley’s funeral, and a first edition copy of Boyd Spahr’s Dickinson Doings. Within Pinkney’s drop file was an article from the Dickinson Alumnus in 1923 about Pinkney’s death, an ad for Pinkney’s ice cream in the Literary Monthly, a few Dickinsonian and Microcosm entries on memories of him, and letters regarding his plaque from the 1960s and 1970s.

After researching in the Dickinson College Archives, I went to the Cumberland County Archives. When I asked if they had any information on these four former slaves, they said I would probably have the most luck researching newspaper articles for more information. They recently subscribed to Newspapers.com, so I began combing through newspaper articles for mention of these men. I had, by far, the most success with Noah Pinkney. Pinkney’s articles included everything from ads for his oysters, information on his fine for selling ice cream on Dickinson College’s property, and ads his new place of business when he moved. There was also quite a bit of information on his daily life in the “Personals” section, in which he was commonly mentioned for his involvement in his church.

In addition to researching Noah Pinkney in Newspapers.com, I also researched Henry Spradley, who also appeared often. His articles were mostly relating to his death and his appointment as a trustee of the A. M. E. Zion church. However, most significantly was a short article that stated not only that Spradley was remembered in a church service at Dickinson but that he was also important enough to the community that committees were created to draft resolutions on his death.

A search on Jim Powell on Newspapers.com resulted in only a handful of articles. The majority of these articles were students’ memories of him as “the little, old colored man who used to amuse people on the streets by making funny faces.” At the same time, he was remembered as being “a Cumberland County Slave” and “who drank croton oil.” A search of Samuel Water revealed no matches.

After this research in the archives, I turned to census searches on Ancestry.com. This yielded me with quite a bit of information on Pinkney, Spradley, and Powell. There are no records of Samuel Water.

In my search of Noah Pinkney, I came across quite a bit of information that cooroborates Spahr’s recollections of Pinkney. I came across a Microcosm entry on him as well as a Dickinsonian article that claimed him the first to get Dickinson students interested in oyster sandwiches.

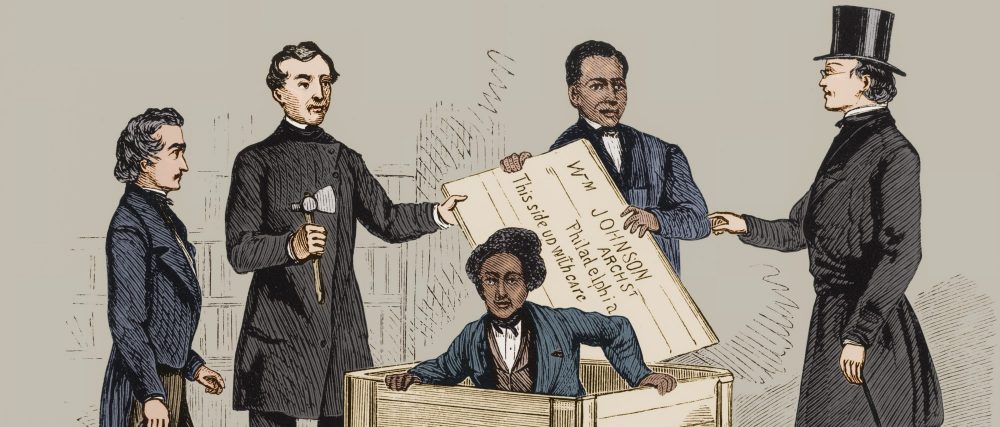

Pinkney sells oysters. Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

Beyond this, I found a Veterans Schedules record from 1890, a death certificate, and Find a Grave entry. These pieces of information stated that his middle name started with an H and that he was born Dec. 31, 1845 in Maryland, was a Civil War veteran, died Aug. 6, 1923, and was buried in the Lincoln Cemetery in Carlisle (Memorial ID number: 152658657). I also found a census from 1910 and a census from 1920. However, in these censuses, there are quite a few interesting changes. In the 1910 census, he was married to Carrie Pinkney, a woman born in Virginia, who was unemployed, was 53 years old, could read and write, and whom he was married to for 35 years. In the 1920 census, Pinkney was married to Nannie J Pinkney who was born around 1880 in Pennsylvania and who could read and write. Both women were supposedly unemployed. Because Spahr’s recollections were published in 1900, the woman who was known as Aunt Pinkney or Aunt Noah would have been Carrie. Another change between the censuses was that despite Pinkney’s listing as employed as a restaurant keeper and as the owner of his house, in 1910 his house was “free,” whereas in 1920, it was mortgaged.

When looking up Henry Spradley, I found two City Directory entries (one from 1882 and one from 1887), a Veterans Burial Card, and Find a Grave entry. Through these sources, I learned that his full name was Henry William Spradley and that he was born in 1833 in Winchester City, Virginia, died Apr. 8, 1897, and was buried in the Lincoln Cemetery in Carlisle (Memorial ID number: 130193369).

Carlisle City Directory in 1882. Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

According to the bio from the Find a Grave page, he was known in military letters and enlistment as Henry Williams, supposedly to hide his slave status. There were two census records of Spradley: one in 1870 and one in 1880. According to the 1870 census, he was a stone maison who was unable to write. He lived with his wife Mima (36 years old, also from Virginia, and unable to read or write) and their three children: Elizabeth (12 years old, born in Virginia, unable to write but attended school), William (nine years old, born in Virginia, and attended school), and Emma (eight months old, born in Pennsylvania). Between the 1870 and 1880 censuses, the family moved from the Carlisle West Ward to 24 West Main Street. In the 1880 census, Spradley was now listed as not being able to read or write and was broadly categorized as a laborer. His wife was still occupied with “Keeping Home” but their children living with them were Elizabeth who was 22, unmarried, and now unable to read or write and Sherly who was six and could read and write but had not attended school yet.

In looking up information on Jim Powell, there was nothing. However, under James Powell, which was most likely his full name, there was a 1910 census. At the time, he was 68 years old, meaning he would have been born around 1848. He lived on North West Street, had been married for 20 years, was born in Virginia, was a wage earner and laborer on a farm, owned his home and did not mortgage it, and could not read or write. His wife, known only on the census as James Powell, was 65 years old, had one child, and was born in Virginia. She did housework for a private family for which she received wages. She could not read or write either.

From these searches so far, I have uncovered descriptions, birth years, and memories of them for all but Samuel Water. Because I now have a better picture of Noah Pinkney and Henry Spradley, my next steps are to continue to look into them more closely. I will do this by searching for information from the A. M. E. Zion church and the Odd Fellows. However, my information on Jim Powell is lacking and I have yet to find anything so far on Samuel Water, so I plan to search for them next in the Dickinson College Archives to see if they and Spradley appear in the Dickinson College janitor file.

Update:

Since drafting this post, I have gone back to the Dickinson College Archives to look through the drop file on custodians at Dickinson. There is still nothing on Samuel Water, but I did find a “Sam” Watts who was a janitor in the 1870s. It seems likely that they are one and the same. I will further look into him at the Cumberland County archives. I also found four main other custodians who were employed as janitors in the 1870s. It seems likely that one or more of them appeared in that picture with Noah Pinkney. I also learned from the drop file that the janitor’s job was to keep vendors like Noah Pinkney from selling on Dickinson property. This rule could explain Pinkney’s fine for selling on the property. I also found a file on the Odd Fellows in personal files of James M. Cook. Between the two pocket book constitutions of the organization, there are two listings for two different Spahr men who were most likely related to Boyd Spahr. In the constitution, one of the first requirements even into the 1920s was that members must be white men over 21 years old. I plan to continue to search for the Odd Fellows at the Cumberland County archives as well as to look into membership at the A. M. E. Zion church. I will also try to find more information on “Sam” Watts. Finally, I will try to identify the picture described in Spahr’s recollection and the janitors who appear in the Noah Pinkney picture.