As I continue to explore sources for the opening chapter of my thesis, I am turning to the contemporary cartoon literature of the 1850s. Visual depictions of commissioners themselves, as well as the arrest, hearing or rendition process, offer valuable insights into how Americans digested and understood the operations of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.

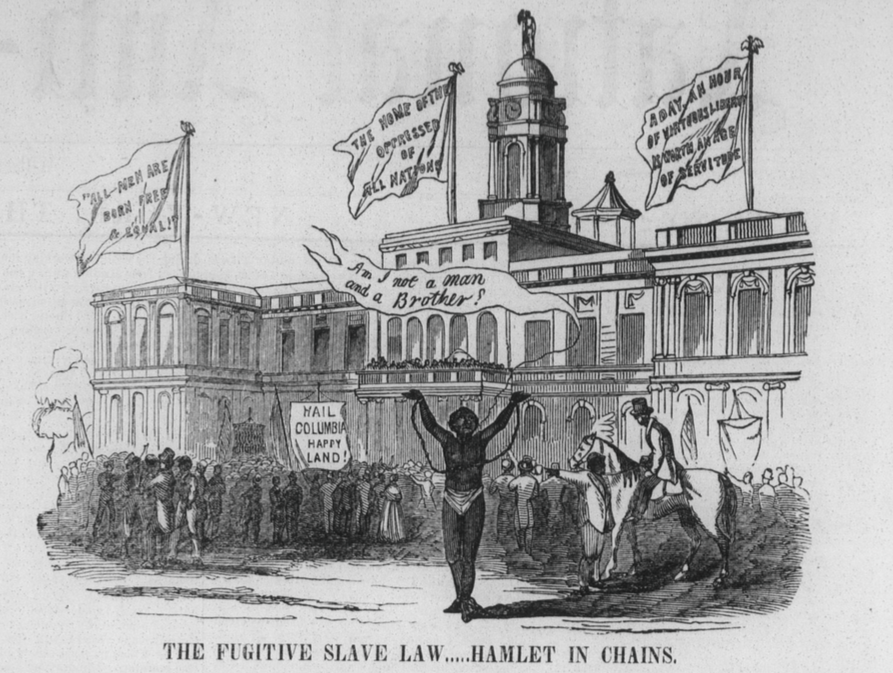

First appearing in the New York Atlas on October 13, 1850, this dramatic and provocative depiction of Hamlet’s rendition was reprinted days later in the National Anti-Slavery Standard. (New York Anti-Slavery Standard, October 17, 1850, Accessible Archives)

Perhaps the first rendering of the law in action, the engraving “Hamlet in Chains” appeared in the New York Atlas on October 13, 1850. The Sunday weekly provided its readers with a dramatized version of the rendition of James Hamlet, the first alleged freedom seeker returned under the auspices of the 1850 law. The Atlas’ engraving contrasts Hamlet’s plight with a cheerful crowd of complicit but inattentive white onlookers, and the nation’s hypocritical claims to be the “home of the oppressed” and a land where “all men are born equal.” In crafting Hamlet’s cry––”Am I not a man and a Brother”––the engravers borrowed a familiar slogan of anti-slavery campaigns, in much the same way they depicted the alleged freedom seeker in a loin cloth, another trope of anti-slavery iconography. A man or horseback, perhaps U.S. Marshal Henry Talmadge, appears ready to forcibly return Hamlet to bondage. Just days later, the engraving was reprinted and praised by another New York serial, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. “The engraving tells its own story,” the paper added, noting that it ably captured “the outrage upon Liberty and Humanity which, in the name of law, was perpetrated in this city.” Hamlet, with his “chained and upraised arms and imploring look to Heaven” was pleading his humanity, the paper claimed, even as “the multitude behind him” seemed indifferent to his fate. [1]

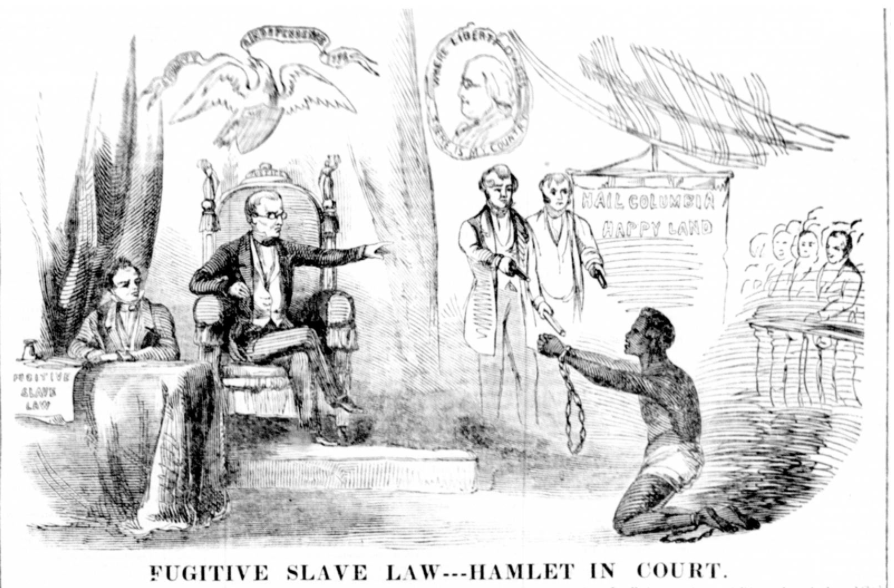

The New York Atlas depicts the rendition hearing of alleged fugitive James Hamlet. (New York Atlas, October 20, 1850)

In its next edition, the Atlas included an engraving of the hearing room that evoked many of the fears Northerners harbored about the immense powers the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law imbued in commissioners. The paper tellingly juxtaposed Hamlet, kneeling before Commissioner Alexander Gardiner and clothed only in a loin cloth, with the assortment of patriotic symbols that adorn the hearing room wall. A banner reading “Hail Columbia, Happy Land,” and a portrait of Benjamin Franklin, bearing the quote “Where Liberty Dwells, There Is My Country,” gives lie to the nation’s complicity with the institution of slavery. As scholar Jeannine DeLombard notes, the kneeling bondsmen clothed only in a loin cloth harkened back to a symbol used in British campaigns against the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, providing readers with “a familiar sentimental icon of the innocent, suffering slave.” [2] Meanwhile, Commissioner Gardiner decrees the fugitive’s fate from aloft a throne, a symbol of despotic authority, while two armed marshals stand poised to whisk Hamlet away. The Atlas‘ depiction of Gardiner, coming just weeks after the law’s passage, reveals a great deal about Northerners’ apprehensions over the drastic expansion of the Federal judiciary, specifically as it manifested itself through the new powers placed in U.S. Commissioners. Connoting Gardiner’s post as U.S. Commissioner with tropes of tyrannical, unchecked power helps illustrate how Northerners opposed to the law viewed the commissioner and the “summary process” of the commissioner’s hearing room.

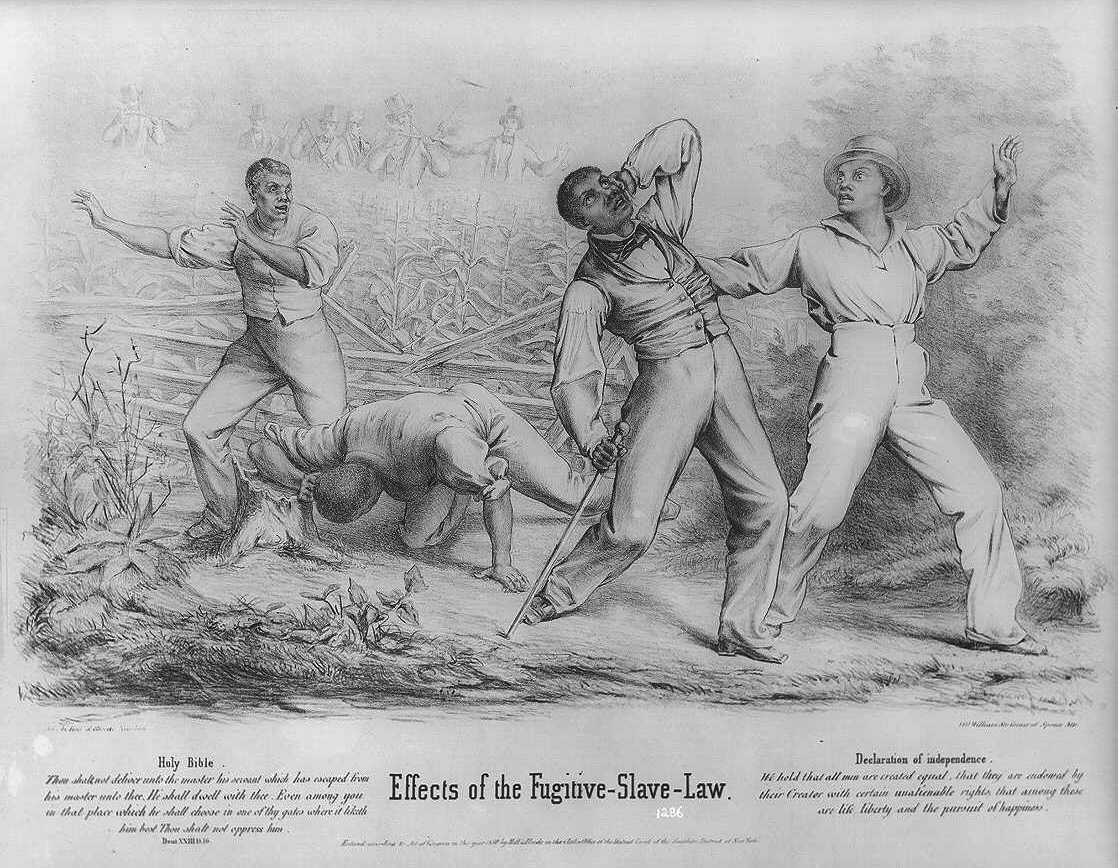

“Effects of the Fugitive-Slave-Law” followed on the heels of the pair of Atlas engravings. (Library of Congress)

Just weeks later, in late October 1850, the New York firm of Hoff & Bloede issued its own engraving, from the hand of Theodor Kaufmann, entitled “Effects of the Fugitive-Slave-Law.” [3] A group of four freedom seekers are pursued by a contingent of armed slave catchers, who are traversing a cornfield. Two slave catchers have fired on the group, and two of the freedom seekers are felled by the bullets. The law, the engraving strongly implies, gives free license to barbaric acts of violence. Much like the Atlas engravings that preceded his own work, Kaufmann contrasts the bloody hunt for freedom seekers with a Bible verse and the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, a not so subtle jab at the law’s flagrant violation of avowed Christian and American principles.

This 1851 engraving “Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law,” was first published in Boston. (Library of Congress)

Later in 1851, a Boston firm released yet another engraving criticizing the law’s operations, fittingly titled “Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law.” [4] On the left, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison fend off what appears to be a U.S. Commissioner or U.S. Marshal, adorned with a star on his hat, who is riding on the back of Secretary of State Daniel Webster. The commissioner, with rope in one hand and a slave collar in the other, bellows, “Don’t back out Webster, if you do we’re ruind,” a reference to Webster’s robust support for the 1850 law, in hopes of gaining Southern backing for the 1852 Whig presidential nomination. Webster, meanwhile, clutches the Constitution in his left hand, a sardonic reference to his avowal to protect the Constitution and Union at all costs. Both the “Practical Illustration” and the Atlas’ earlier engraving “Hamlet in Court,” offer unflattering depictions of commissioners. However, whereas the Atlas portrayed Commissioner Gardiner as a source of despotic, unchecked power, the commissioner in the “Practical Illustration” cartoon appears rougher and cruder, a gruff hireling engaged in a dirty, nefarious business.

[1] “The Fugitive Slave Law…. Hamlet in Chains,” New York National Anti-Slavery Standard, October 17, 1850; Jeannine Marie DeLombard, Slavery on Trial: Law, Abolitionism, and Print Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 35-36. [2] DeLombard, Slavery on Trial, 35-38. [3] Bibliographic information from the Library of Congress. [4] Bibliographic information from the Library of Congress; the engraving has been attributed to the artist Edward Williams Clay.

Leave a Reply