Dec

8

Studying Authoritarianism and Change in the Middle East and North Africa

December 8, 2023 | | Leave a Comment

Understanding authoritarianism and change in MENA is a complex topic that scholars in comparative politics and political science have attempted to understand for decades. Ultimately, there is not one distinguishing factor that sets MENA apart, but rather a combination of them. MENA is unique given the high presence of resource endowments, which have crucial links to authoritarianism. The repression effect and spending effect explain that resource-rich countries rely on less taxation and use oil rents to fund coercive apparatuses that allow authoritarian leaders unprecedented power. This allows them to focus less on legitimacy to demonstrate power and instead use repression and violence against the population. Additionally, the labor capacity of each state in comparison to resource wealth explains some of the deprivation of rights of civilians and the frustration that culminated in the uprisings in 2011. The thematic study of these economic factors is covered in depth in Cammet, Diwan, Richards, and Waterbury, and is important to understanding the region as a whole.

However, looking at specific cases, through the Khatib and Lust book as well as Lisa Wedeen’s book on Syria can help to explain more specific case studies. Through this analysis, the differentiation between regime type and colonial history demonstrates some of the institutional and structural barriers that prevent the spread of democracy in the region, and also the intense repression used by regimes. Personalist regimes foster an environment in which one individual retains power and creates a system of repression and refusal to abstain from power, as seen in Libya and Syria. Military regimes are often less functional and highly repressive, yet hold on to their power less tightly, resulting in different turnovers, such as Egypt. Monarchies are prevalent in the GCC and generate power through their traditionalist patterns, often thriving on patronage and crony capitalism. Additionally, MENA stems from colonial history after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, resulting in struggles for nationalism and national divisions in many countries, such as Libya which is currently at civil war as a result.

Ultimately, looking at the region through just one lens does a disservice to the complexity of the authoritarian systems in place and the region’s general resistance to democratization. Looking at the region from both an economic and political standpoint is perhaps the most important tool for understanding the region, provided how intertwined those elements are in these resource-rich countries. Yet to understand one country is not to understand them all, so more specific case studies remain necessary when viewing the authoritarianism and uprisings of these states.

Nov

1

Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown: Handling public dissent in MENA’s monarchies

November 1, 2023 | | Leave a Comment

Monarchical rulers constantly have challenges that not only threaten their survival but also the scope of their power, as exemplified by the famous Shakespeare quote, “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown”. The Middle East in the last 15 years has been a great example of this with the Arab uprisings that began in 2011, spreading across the region like wildfire. The monarchies of the GCC, Jordan, and Morocco were plagued with these revolts just as much as the rest of the region and were faced with the complex nature of putting to ease the resistance while maintaining their legitimacy and control which relies on limited political liberalization and democratization.

To understand how these monarchies can confront such uprisings, it’s first important to understand the challenges that this regime type is specifically plagued by. Monarchies establish their people as subjects rather than citizens which means that the people are less passive and have less power over the governing of their nation. As a result, there is little room for public opinion in the monarchy as it can allow for budding unrest. Monarchies also rely on a balance between coercion and legitimacy to rule, emphasizing a system of patronage and repression. This patronage is especially true in the GCC, which are dynastic monarchies, known for the distribution of the ruling family throughout all levels of bureaucracy and institutions and thus have dynamic control of government. Patronage is specifically destructive regarding the recent youth bulge in which younger, more qualified individuals are being passed over for positions in favor of the family members who support the regime, stirring dissent. The lack of civil society among these institutions has made it easier to keep these brewing protests in check, however, the emergence of new media is a growing threat as it provides not only a new platform for engagement and political discussion for subjects but also the sharing of ideas beyond state borders. This is exemplified in the Feb20 Movement in Morocco on Facebook before the uprising in 2011 as well as the February 14 Movement in Bahrain that was primarily organized through various forums frequented by youth activists. Individuals with no prior activist experience suddenly had a platform. Additionally, new media, including television, allows people in these monarchies to see the uprisings already happening in other nations, exemplifying the demonstration effect. In Morocco, what started as 6 women protesting during Ramadan under the page MALI in 2009 grew into a virtual community that, at times, called for reforms as radical as overhauling the regime. Together, Feb20 was able to organize protests in multiple cities, and network with established senior activist institutions and tens of thousands of people. Altogether, new media is a new enemy that these monarchies have to use their coercion and patronage to control and was one they were wholly unprepared for in 2011.

Despite the obvious gaps for dissent that these monarchies face in MENA, they have developed a variety of tools to manage them since their founding and the birth of the Arab Spring. It’s important to understand the difference between monarchies in the region as it can often sway how they handle the issues. As mentioned, the GCC are dynastic monarchies however, Jordan and Morocco are linchpin monarchies in which the monarch takes a step back from politics by electing a prime minister and cabinet. Both types of monarchies rely on similar methods, meaning repression, waiting out the revolts, and compromise, however, they go about them slightly differently. Linchpin monarchies like Jordan and Morocco may have cabinets and prime ministers, however, these government officials are very much still in the King’s pocket as he determines the extent of their power, thus having them act largely in his favor. However, during the uprisings, these Kings were able to use the cabinet as a sort of shield for plausible deniability, pushing off the responsibility for the issues of revolt to the other officials in the eyes of the public. Additionally, they would set up committees to review the Constitutions in the name of reformation, however, little reform would be done. This was seen in Morocco when King Mohammed VI created a committee of 18 loyal civil servants to preside over the constitutional reforms. These committee members would then continue to compromise with the activist group’s claims against the constitution to keep the King’s power strong. After so many compromises, there would be very little change and Mohammed’s power remained largely unchecked while he could claim that reform had in fact been made. The new media was used to his advantage as well, as compromising took so long that the subjects were able to see the violence in the other arab nations that had revolted and chose to diminish their own activism. Repression was used in moderation in these nations, namely in the large protests, however, violence was less pronounced.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/18/bahrain-destroys-pearl-roundabout

The same cannot be said for the dynastic monarchies of the GCC, which did not have a cabinet or prime minister to shield the monarch from responsibility. As a result, the monarchs relied heavily on repression in shutting down the movements, as exemplified in Bahrain at the Pearl Roundabout which was razed on March 18th as 2500 troops from the GCC joint military force moved into the state to violently repress the remaining revolters (as seen in the image). Today the Pearl Roundabout is a distant memory with no concrete existence as it became a symbol of resistance. Before repression became a full-force effort, the monarchs relied on dialogue to try to appease the subjects. They often would use the idea of “I hear you” and the promise of reform to slow the revolts, yet very little actual change was enacted. However, they were successful enough and this, once again, allowed the protests to die down as activists saw the brutal results from the other Arab Springs. Essentially, these tools of coercion/patronage, violence, and the use of legitimacy and power to postpone real change are the strongest in the monarchical arsenal at limiting unrest among the people, allowing them to overcome the various challenges that historically have presented themselves.

Oct

6

A Review of “A Siege of Salt and Sands”: The Effects of Climate Change on Tunisia and MENA

October 6, 2023 | | Leave a Comment

The Middle East and North Africa is the most water-scarce region in the world and one of the most food insecure as well, which is only made worse by the constant economic instability and increasing effects of climate change. “A Siege of Salt and Sands” takes Tunisia as a case study of the previous issues in regard to climate change, focusing on both coastal city life and the desert climate to the south. The documentary does a good job of tying political issues to the worsening effects of climate change by addressing the start of the Arab Spring in 2010. While the Arab Uprising in Tunisia was generally focused on economic stagnation with the negative effects of structural adjustment and political corruption, the government’s lack of action on the environment has contributed to the frustration of many Tunisians.

Earth.org

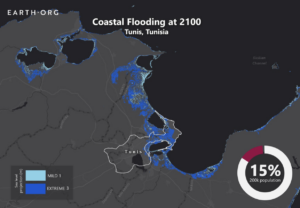

Looking first at “the Salt”, or coastal towns, Kerkennah and Djerba provide evidence of the impacts of climate change both in rising sea levels and in droughts. The documentary shows many civilians in the towns, including fishermen who make their living off of the sea. They claim that in two years there will be no fish left and that droughts have killed 65% of the date palms in their town. Additionally, with no rain in over a year when the film was taken, this affects not only crop production but also access to drinking water as that is a major source for many. Regarding sea levels, they have risen 25-30 cm since the effects of climate change were first seen in the region. The people worry about losing their homes and even Kerkennah turning into inlets soon, as demonstrated by the projected effects of rising sea levels in the map.

Further south, “the Sands” are also experiencing the effects of climate change and the resulting droughts through increasing desertification. Much like in the north, the seasons have changed to be much warmer and windier, with little to no rain. Some areas hadn’t seen rain in three years. The already dry environment is only becoming drier and sand is encroaching on many towns, getting into houses, covering fertile land, and paralyzing the development of the region. This desertification poses a serious threat as 64% of Tunisia’s surface is threatened by desertification and 23% of that has already been desertified. Water access is a prominent issue as well, with families being forced to choose to water their crops or provide themselves with drinking water. One farmer included that wells are the solution but the government isn’t providing enough of them, instead making the civilians pay for water with money they don’t have. Even with water access, it tends not to be enough to irrigate entire fields, threatening the agricultural industry and the standard of living for many in the area.

The documentary highlights the complexity that climate change has brought to already damaging issues in the region such as water shortage, the struggling agricultural sector, and desertification. Given the political and economic context that has been covered in class, it’s clear how the interaction of these environmental issues has only been complicated by the structural adjustment of the region and the increasing pressure on the government. It also highlights some of the positive changes Tunisia has made towards the end, including being only the third country to include a clause about climate change in its constitution. This film overall does a great job at providing civilian and scientific accounts for the environmental struggles plaguing the nation and the resulting societal and economic impacts of them to help make the topic more digestible and personal than it traditionally is.

“A Siege of Salt and Sand”. Directed by Sam McNeil, produced by Sam McNeil and Radhouane Addala, 2014.

Cammett, Melani. A Political Economy of the Middle East. Available from: MBS Direct, (4th Edition). Taylor & Francis, 2018.

Sep

25

Rentierism and Democracy

September 25, 2023 | | 2 Comments

The Middle East and North Africa region is characterized by the rest of the world as being incredibly resistant to democracy, prompting a specific focus on authoritarianism and the idea of a rentier state. Rentier states have rents on specific products, which in this case is oil, and charge foreigners for access to those rents. That money goes directly into the hands of the government creating a strong central power and impacting social and political outcomes. The rents themselves serve as a sign of societal disturbance, but it’s the resulting interactions they have with the government, civilians, and the economy that are particularly damaging.

In his study, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”, Michael Ross looks at the role of oil rents on democracy in the Middle East and globally. Specifically, he looks at the rentier effect, where resource-rich countries use low tax rates and patronage to avoid accountability from citizens. In understanding this tax effect, the motto is essential, “no representation without taxation”. The oil industry requires less labor and puts money directly into government funds, therefore, avoiding the involvement of civilians altogether. This money instead can go towards strengthening patronage. Ultimately, as a result of money accruing directly to the state, the civilians feel less entitled to democracy and representation, thus damaging political and social outcomes.

Along with using the money to bolster the government, it is also used to put down citizens. The repression effect is another topic that Ross talks about to explain that as resource wealth grows, the government will be more likely to spend it on internal security. Building up the military creates a power imbalance in which citizens don’t feel secure raising their voices. Many resource-rich countries have a mukhabarat state, in which there is an internal intelligence network where one can never be sure that their neighbor isn’t spying on them. It’s essentially like the Soviet KGB or the police under Saddam Hussein.

World Bank, Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis

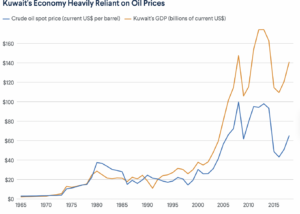

Regarding the economy, resource-rich countries often find their private sector lacking as a result of a large and overbearing public sector featuring the oil industry. Due to the funds from these rents accruing directly from the state, the government has a more direct hand in controlling the public sector, which can lead to large population struggles if the industry is impacted.

This was seen with the 2008 recession in which many countries in the Middle East, specifically resource rich countries, had lingering effects of economic struggle as the oil industry’s success declined. An example of this would be Kuwait which, as evidenced by the graph, had a decrease in GDP when oil prices decreased during the recession. Additionally, the government also has a heavy hand in setting wages and the other industries that can find success, although they tend to be limited.

Ross claims that this is also not limited to just the Middle East or small countries. In fact, these results regarding a struggle for democracy in oil rent states are seen across the world. The interaction of these rents through the government and thus civilians and the economy makes it commanding and detrimental to democratization and stability of social and political life.

Work Cited:

Ross, Michael Lewin. 2001. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics 53, 3. (Apr.): 325-361

Cammett, Diwan, Richards, & Waterbury Chapter 9, 319-354

Sep

20

Is the Western Lens of Democratization Applicable in MENA? Analyzing Lisa Anderson’s Article “Searching for Where the Light Shines: Studying Democratization in the Middle East”

September 20, 2023 | | Leave a Comment

In Lisa Anderson’s 2006 article, “Searching for Where the Light Shines: Studying Democratization in the Middle East”, she argues that the model for democracy, which is idealized by the Western world and the US specifically, does not necessarily apply to the region of the Middle East. Western foreign policy puts a large emphasis on democracy and a global movement towards liberalization. Throughout history trends of modernization, transitionology, and the most recent success of “third-wave” democracy have been the primary focus of the global political science lens on development and regimes. And yet it meets resistance in the Middle East specifically. Anderson cites many issues with political scientists attempting to understand the political forces in the Middle East and North Africa through the lens of democratization, starting with the new state creations in the 20th century and including the modern economies of each country.

A democracy requires destabilizing a nation both socially and economically and a reliance on civil society to make a functioning state. The nations of the Middle East were created from colonial parentage after the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War 1, making them fairly young nations, yet still carrying the burden of the prior history in the region. Modern political scientists choose to view these as new states, but Anderson claims they neglect to look at the local, nonstate networks that were already in place. As a result, as these nations have developed, their governments have a frail foundational view of democracy and a reliance on coercion and establishing legitimacy to function. Most attempts at democracy have been brief or surface-level on the part of the government to gain international support. Much of the Middle East and North Africa lacks cultural unity as a result of their more recent formation and often have governments that are resource-reliant and thus less reliant on the citizens. Democracy, as a result, serves less of a purpose to the authoritarian regimes that are already in place.

Ultimately, Anderson says that despite democracies’ success globally and most recently in Latin America in the ’80s and ’90s, the Middle East is a case study that cannot be viewed through that same lens. Through her analysis, she makes a point of emphasizing that the region must be viewed in more of an area study than just a global context, a lesson that can be taken throughout this course. Instead of using an American political scientist’s perspective, the country must be understood from the inside out. The culture of the Middle East as a result of their Ottoman history, the strong presence of Islam, and their complicated economic situations as a result of natural resources, such as oil, make them entirely different from the deeply studied regions they’re compared to. Viewing the Middle East and North Africa with these differences in mind before applying that Western mindset will be crucial to fully understanding the politics of this region.

Additionally, Anderson’s article was written before the Arab uprisings in 2010 and 2011 in which citizens revolted against their governments across much of the region, starting in Tunisia and spreading across North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. As the region experienced changes in the oil markets and thus unreliable economies and governments, and a perception of decreased social satisfaction, democracy began to look more appealing to the citizens. As a result, a sort of civil society was built among the people in a way that hadn’t been seen before. These uprisings had a variety of impacts, but the new emphasis on citizens and representation of their needs, specifically the non-elites, brought an aspect of democratization that the region lacked before. This is not to say that the Western lens of democratization is suddenly applicable to the region, but perhaps these uprisings add a qualification to Anderson’s claims as the nations may move in a new, more liberal direction.

Work Cited:

Anderson, Lisa. 2006. “Searching where the light shines: studying democratization in the Middle East” Annual Review of Political Science 9:189–214