As I look at what my life will become when I graduate in May and move past the limestone, as they say here at Dickinson, I have been looking more at my love of architecture and cities and the intersection with climate change. These thoughts recently made it to the forefront of my mind as I came across some interesting new studies on the longevity of contemporary building styles. I will back up some first. I have been planning on attending architecture school for some time now. I am still unsure of when that will be, but I will make that move at some point. I came to this decision after some realization that soon major cities are going to need rebuilding and expansion. I will touch more on that shortly, but first I want to be a part of this next generation of builders. The ones that will help shape the physical layout of a rapidly transforming global society. Imagine the infrastructure change as society shifts away from the heavily petroleum based ways that infiltrate nearly every aspect of life. Buildings redesigned for efficiency, transportation networks reinvented, social spaces that allow for more community building. This newly designed world will have to be adapted to the new climate that humans have wrought.

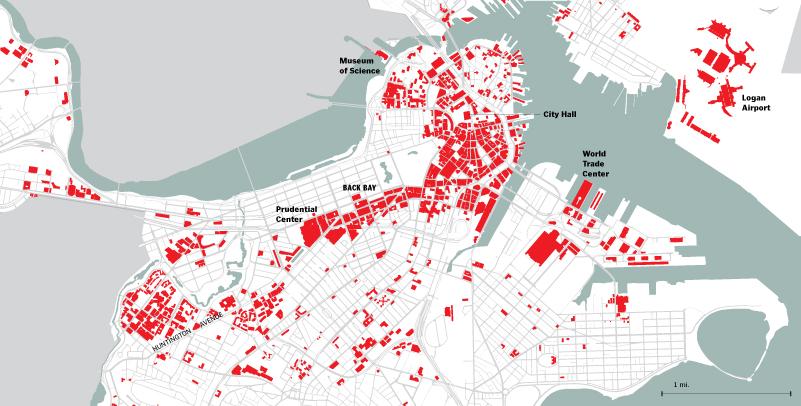

The article that recently brought these thoughts to the forefront of my mind came from Fast Company’s design section. It discusses the risk that climate change poses to modern buildings. It reports on a journal article that highlights the potential danger of concrete degradation from acid rain. Imagine how much concrete you come into contact with everyday. It is everywhere, and according to this study if you live in a city like Boston 60% of it could be gone by 2050. Their projections are admittedly for a worst case scenario, but in a country that already spends over $4 billion dollars on concrete bridge repair it is a dangerous scenario. While this study is focused on the effects of carbonation and chlorination of concrete, which is a coastal effect, I does make me think of the limestone here at Dickinson. Being a locally available and excellent building material, the glorious sedimentary rock makes up much of Dickinson’s campus. However, anyone who has ever been in an Earth Science course or has been rock climbing in the area knows that limestone is not the most robust of materials. It is a decent enough building material, but it weathers (chemically and physically) incredibly easily. Just pour some vinegar on a block of limestone to see. Household vinegar has a pH of 2, while clean rain is generally between 5.0 and 5.5. The pH of rain in Carlisle, where Dickinson is located has been seen as low as 4.3. While this may not create the immediate visual weathering effect vinegar does, increased acidity will lead to much more rapid breakdown of the limestone. To tie this all together I would ask that you think about how we will be building in the future. The planet has changed and the new rules are going to make it much harder to design and build. I am excited for this opportunity though. We are headed into a future of rapid urbanization and the need for innovative systems of buildings that help facilitate strong community and clean living (clean in the no-carbon sense). As new communities are planned, much more diverse buildings will be built in order to adapt to local conditions brought on by global climate change. The behemoth concrete giants of the past are no longer applicable. Buildings will need to be dynamic and utilize materials that will hold up to acid rain, flooding, or mega-typhoons.