Here is my talk from CAMWS 2015 on digital text annotation, for those many who were unable or disinclined to come to an 8:00 p.m. (!) session. Please leave a comment if you like.

The field of digital classics is very focused right now on the unsolved problem of how to present scholarly editions of Latin and Greek texts online, and in particular how to represent the apparatus criticus and link to manuscript evidence. Not enough attention, I would suggest, has been paid to the question of how to best present classical texts for ordinary students and readers of Latin and Greek in the digital realm.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, Book 1, ed. Max Bänziger (Monumenta Informatik) with links to manuscripts and citation links. http://monumenta.ch/latein/

A deluge of plain text is not going to do it, I think we would all agree. Readers and learners typically want to know “what does this word mean?” and “what’s going on with the grammar here?” Plain digitized texts, or texts enhanced with links to manuscript images like this one provide no guidance on these matters, since they are designed for advanced scholars.

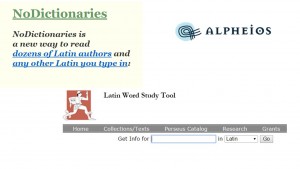

The main focus in tool development for readers to deal with these questions has been automatic parsers linked to dictionaries, like nodictionaries.com, the Alpheios plugin, or the Perseus Word Study Tool. But the unreliability of those tools, not to mention their perceived role as crutches, has given them a poor reputation among teachers and thoughtful students alike.

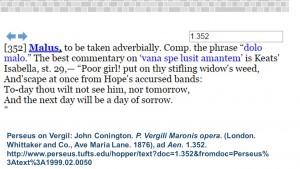

Perseus on Vergil: John Conington. P. Vergili Maronis opera. (London. Whittaker and Co., Ave Maria Lane. 1876), ad Aen. 1.352.

Another tack has been to digitize older, public domain commentaries like Conington’s Vergil. Perseus includes several such works. But whatever the merits of these works in their day, they are often opaque to learners and readers now. Older commentators tend to assume an audience that has already been well-trained in Latin, and just needs a little reminder of a common construction, or might enjoy an apposite quotation from Keats.

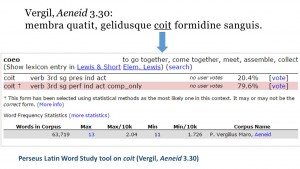

The Perseus Word Study tool is designed to provide more basic information. It does its best to guess which dictionary head word a given form derives from, then gives a brief definition, with links to Lewis & Short, and a series of suggested parsings. It guesses the correct parsing based on frequency, and includes a voting feature that lets you select which parsing you think is best, and what definition you think best for the context.

This voting feature is slowly improving the accuracy of the Word Study Tool, but even if the parsing happens to be right (which it is not in this particular case), the dictionary data itself is often not helpful, because the choices are the very brief “short defs” and the full fire hose of Lewis & Short.

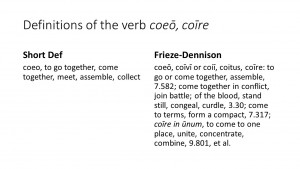

A good but under-used solution to this problem of too little or too much is the author-specific dictionary of the type that is contained in many older school editions, such as Henry Simmons Frieze’s editions of the works of Vergil.

This is his version of the Aeneid, revised in 1902 by Walter Dennison. Freize published a full dictionary to all the works of Vergil in various revisions over the 1880s and 90s, and Dennison revised it slightly to focus on the Aeneid material only for this edition.

Note that Frieze includes all the principal parts, with macrons; a number of Vergilian definitions not included in the Short Def, and citations for all the particular senses. Frieze spent his career at the University of Michigan teaching Vergil and other Latin authors, and working on his Vergil editions. His translations are expert, and his philological acumen at a very high standard.

Frieze does equally well in the sphere of proper names, where automatic tools are often helpless to distinguish between homonymous figures. This is precious intelligence for readers of Vergil. In 2014 I set out to properly digitize Frieze’s Vergilian dictionary with the ultimate goal of creating running vocabulary lists for the whole Aeneid.

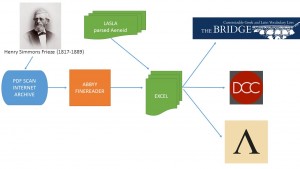

The process went as follows. The .pdf scan from the Internet Archive went through a OCR program called ABBYY Finereader. The resulting text went into an Excel spreadsheet. To Frieze’s definitions we added frequency data derived from a human inspection and analysis of every word in the Aeneid. This work was carried out by teams at the Laboratoire d’Analyse Statistique des Langues Anciennes (LASLA) at the Université de Liège in Belgium.

Once this process was complete and the spreadsheet made, it was uploaded into Drupal, where the database version on DCC can now be searched, ordered by frequency, and downloaded in various formats. It can be reused at will under a Creative Commons license. It will also form the basis for the running lists in our edition of the Aeneid now in development.

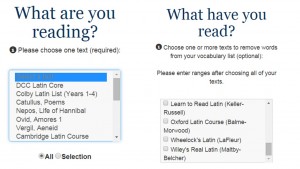

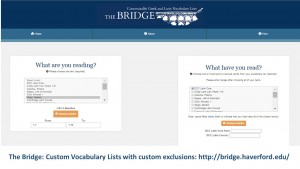

The Bridge, developed at Haverford, allows the making of accurate vocabulary lists for custom ranges of text

Putting the information in a spreadsheet keyed to LASLA lemmata made it possible to share with The Bridge, a new tool developed by Bret Mulligan at Haverford College. This allows the user to specify a particular line range and get vocabulary lists, either all words, or with certain words excluded, like the DCC Core vocabulary, or the vocabulary of a common introductory textbook.

The important thing to emphasize is that the lists include not the headwords that are statistically likely to appear in the passage, but (barring minor textual difficulties) those that actually do, and no others. I also put a column in the spreadsheet listing the headwords as used by Logeion, and thanks to Helma Dik is it also available there.

The facilities are now starting to exist by which accurate lexical information such as this can be shared by the community of classicists, and the Bridge and Logeion are in the vanguard of this development. By excavating and reclaiming more author-specific dictionaries we can all contribute to this positive change and get the resources that students and readers need. Effective digitization of older hand-made tools can be more effective than the creation of new automatic tools.

II. Goodell’s Greek Grammar

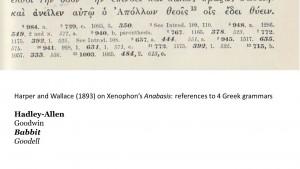

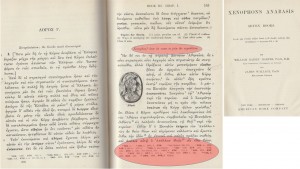

Harper and Wallace’s edition of the Anabasis annotates with references to four different school grammars

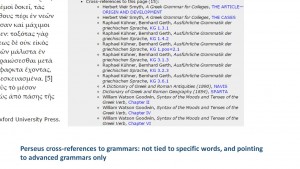

Perseus cross-references to grammars: not tied to specific words, and pointing to advanced grammars only

Another nice feature of older school editions that can be usefully recuperated in the digital realm is reference to grammars. A learner or reader is likely to ask, what’s going on with the grammar in this passage? What rule covers this? Or is it somehow exceptional? This question was sometimes dealt with in older school editions by simply giving a citation from a widely-used grammar book–or to four of them, as in the case of Harper and Wallace’s edition of Xenophon’s Anabasis–and relying on the student to go look it up. In olden days, perhaps they did. The internet allows for much easier cross-referencing of this kind. Sometimes Perseus operates in this way, as with T. Rice Holmes’ Caesar Gallic War, Perseus makes the cross-references clickable.

More common in Perseus is a kind of general reference to grammars for an entire page, typically to a large discussion of “the tenses” or “the cases.” Here we see a page of Thucydides with references to Smyth’s discussion of the article, and the cases, and similar links Kühner-Gerth, and Goodwin’s Moods and Tenses. None of this is keyed to a particular word or phrase in the text. Another issue here is that all the Greek grammars at Perseus are advanced.

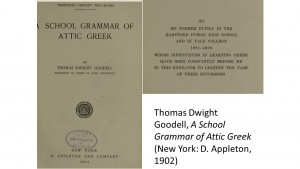

In fact none of the more elementary Greek grammars like those referred to by Harper and Wallace have been digitized properly, to my knowledge. While reading Harper and Wallace’s edition of the Anabasis two summer ago I became aware of Thomas Dwight Goodell’s excellent School Grammar of Attic Greek (1902), whose dedication speaks to the attitude of a gifted teacher.

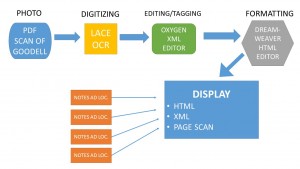

With help from Bruce Robertson at Mount Allison University and some of my students I set about digitizing Goodell. This involved the hand-correction and tagging of the raw OCR output provided by Robertson’s Lace, which in turn went back into Lace and improved its accuracy. This corrected output was then tagged in XML using Oxygen, and converted into html. The html pages were edited by Meagan Ayer, and the navigation created by Ryan Burke at Dickinson.

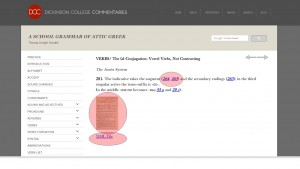

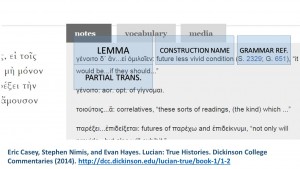

Now we have an easily navigated, attractive Greek grammar, including page images, downloadable XML, and linked cross-references. We can now link directly to that in the notes fields of DCC.

The aim here is to simplify annotation, and obviate the need to re-explain grammatical features. It has the pedagogical value of not being a crutch, in that the reader must make his or her own connection between the passage at hand and the relevant rule. The typical annotation of this type has four elements: the lemma, the name of the construction, the grammar cross-reference, and a partial translation. One could remove the second and fourth of these elements.

The internet has made all of us potential publishers, and there are many classical teachers out there creating resources for their own students and sharing them with the world. The future, I believe, lies in collaboration, but not just collaboration between ourselves. We should also open ourselves to collaboration with men like Henry Simmons Frieze and Thomas Dwight Goodell, and adapt their durable work to the needs of contemporary readers and students.