The Last Supper

by Anna Ryan Radigan

On the third day of our Fashion Mosaic research trip to Italy, on March 6, 2024, we visited Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper in Milan. None of us had actually seen it before, though most of us were familiar with it, as I was since I’m an art history major. For this Mosaic, we visited the painting because of the work’s representation of a specific type of textile, a painted tablecloth, and because of its importance to the value of beauty and history in Italian culture.

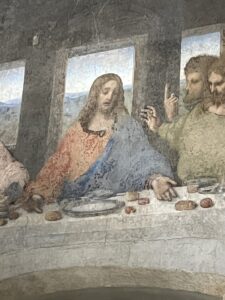

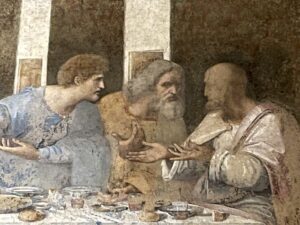

Leonardo Da Vinci started to paint the piece in 1495 during the height of the Renaissance. The painting takes up an entire wall in the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, a smaller monastery that is still in use to this day. The painting is around twenty-nine feet long and fifteen feet high, making the subjects life-sized. Leonardo painted thirteen figures. Jesus Christ and the twelve apostles sit at a long dinner table laid with bread, fruit, eel, lamb and wine. Christ sits in the center with the twelve apostles on either side, all expressing different emotions and gestures. This work is especially significant because it represents Christ’s announcement that one of his apostles will betray him, leading to his death in the Gospel of John. You can tell which figure is the betrayer by looking closely at how each apostle is fashioned; more specifically, one stands out in terms of their appearance and stance. Judas, the third apostle from Christ’s right hand, is depicted outwards, towards the viewers and over the table, in comparison to the other gospels who sit upright. Judas has a darker complexion, and he reaches for the same plate on the table as Christ, hinting at their tension.

Our guide for our visit to The Last Supper, Elisa Marchetti, explained that many people think it’s quite a miracle that the painting is even standing today. There has been discourse around the rehabilitation of the painting after the Santa Maria delle Grazie was struck by a Royal Air Force bomb in August of 1943, the peak of World War II in Italy. Luckily, The Last Supper was not struck and miraculously survived by a hair. The two walls surrounding the work collapsed and left The Last Supper standing alone.

Our guide explained that The Last Supper has experienced problems with preservation and restoration ever since its creation. Today the experts monitor humidity, light, temperature, and the number of people viewing the work at once in order to keep the paint from chipping off, a problem they have faced since the Renaissance. Our guide Elisa Marchetti additionally quipped that women have been key to the preservation and restoration issues while men were responsible for damaging it through war and misconceptions about proper restoration techniques because they didn’t understand the actual composition of the painting. In the 1800s, Stefano Barezzi, a conservator, believed the work was a fresco and he damaged the wall trying to paint on top of it. This mistake removed the tempura paint in certain areas and left duller colors behind (tempura is a method of delicate painting using egg yolk and water. It dries faster and is incredibly precise). Later, Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, a female restoration expert who was part of the Artistic and Historical Heritage in Milan during the 1970s, completed an entire clean-up of the painting in 1999.

While The Last Supper continues to face problems of chipping and aging, it has slowed sufficiently with contemporary conservation efforts that it now leaves more time for researchers like us to experience its elegance and representation of Italian beauty, gestures, and historical culture. I would love to delve into the origins of the tablecloth & how it pertains to fashion but that could be for another blog post. Stay tuned and I hope you learned something new or simply enjoyed reading.

While The Last Supper continues to face problems of chipping and aging, it has slowed sufficiently with contemporary conservation efforts that it now leaves more time for researchers like us to experience its elegance and representation of Italian beauty, gestures, and historical culture. I would love to delve into the origins of the tablecloth & how it pertains to fashion but that could be for another blog post. Stay tuned and I hope you learned something new or simply enjoyed reading.

– Anna Ryan Radigan 🙂