In Steven Moffat’s revision of Conan Doyle’s original Sherlock Holmes series, Moffat brings Holmes and company into the modern era. This modern view allows us to view Holmes through a different lens, in this case seeing the issues that Doyle discusses in his series through a modern lens. Juxtaposing the original story with the revisions that Moffat has made can show us how our set of societal norms has changed since Doyle’s 19th century detective was first conceived.

Sherlock Series 2 – A Scandal in Belgravia Trailer

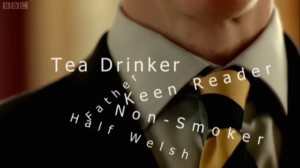

A Scandal in Belgravia parallels Doyle’s novel in a number of ways. Watson blogs rather than narrates. In fact, his blog takes the place of Doyle’s novel in a number of ways, even sharing the same titles as Doyle’s original stories. The blog idea is also shown with typography, showing Sherlock’s deductions as he’s thinking about possibilities, differentiating from Guy Richie’s films where Sherlock verbalizes his deductions and courses of action. The audience is also still placed in a passive state in Moffat’s films, the same as in Doyle’s stories. In Doyle’s stories, we’re reading Watson’s account of his and Sherlock’s adventures, in Moffat’s films we are often placed behind windows, looking through mirrors. It detaches us from the action, forcing us to realize that we have absolutely no participation in what is going on*. We are helpless and reliant on Holmes to solve the case.

In the case of A Scandal in Belgravia, Sherlock must solve Irene Adler, the same woman from A Scandal in Bohemia, with a modern twist. Adler is more fully developed in Moffat’s film, the subtlety traded for the detail needed for a film medium. From the 19th century story to the 21st century film, she transforms from a simple actress into a dominatrix. Despite the shock value, this isn’t much of a stretch for Doyle’s novel and in fact is a fairly good modern translation of occupation. Much as C.S. Lewis vaguely describes many of his characters, leaving much up to the reader’s imagination, Conan Doyle leaves much up to translation about Adler. It is our romanticized view of the past that causes us to believe that Irene Adler was of the same occupation that our culture is currently obsessed with. We now elevate actors and actresses to celebrity status, following them in tabloids and entertainment shows. However, in the 19th century, the job of an actress was not considered appropriate for a woman, much as our heteronormative society would consider the job of a dominatrix to be an inappropriate occupation for an intelligent, sophisticated woman, something Adler proves herself to be numerous times.

This is a theme that both the original text and Moffat’s revision do an excellent job of capturing. Doyle very specifically describes Adler as having the, “mind of a man”. In the original story, the simple idea that a woman could be on the same level as a man was shock value enough, not to mention that this woman was an actress. Moffat is able to capture that same feeling, but with the subtle change that we are now shocked that someone is on the same level as Holmes, that she can intrigue even the great Sherlock Holmes to the point of emotion. We are shocked by her occupation, the modern equivalent of a 19th century actress (in fact, Mycroft refers to her as an actress of sorts in the film). We are essentially shocked by the same things that Doyle proposed in his novel.

Sherlock meets the naked Irene Adler – Sherlock Series 2 – BBC

Adler’s occupation fits her characterization though. She is presented as having “the mind of a man” and so her role as a dominatrix, reinforces the idea that she is given dominance over others (in the novel, Sherlock is said to have considered her to be above all other women). It isn’t much of a stretch to consider that Irene Adler might identify as a man, despite biologically being female. This idea isn’t even specific to Moffat’s version, it can be inferred from the very description of her. As every other element of Doyle’s story creates a shock of sorts, the idea that Adler could be a transgender, genius with a socially inappropriate occupation and who can defeat Sherlock Holmes is rather fitting with the rest of the novel.

*Note: As an interesting note, Moffat has also included active audience participation in his television episodes before. In his episode of Doctor Who, Blink, the villains can be turned to stone when they are being observed. During the episode, there are numerous times when the characters are not looking at the villains, but the audience is, thus they remain stone.

Very nice comparison of the modern era with the original text. Just as in “Srsly Sherlocked” I agree that it is a great new way to capture this story.