https://www.pexels.com/photo/brown-wooden-house-on-green-grass-field-near-green-trees-and-mountains-4275885/

The German language has a unique capacity for putting words to intricate facets of the human experience. From Waldeinsamkeit, the feeling of connection and solitude experienced in nature, to the more commonly used Wanderlust, describing the strong desire to travel and experience the world, there are numerous feelings and experiences where English falls short that German neatly describes. One of the most interesting is Fernweh, translated literally as “far-sickness.” Contrasting the familiar Heimweh, or homesickness, Fernweh describes the melancholy of longing to travel. A cousin to Wanderlust, Fernweh articulates the desire to travel with less passion and zest. Teju Cole (2015) describes it as, “the silver lining of melancholia around the cloud of happiness about being far from home.” As its etymology indicates, Fernweh is not a buoyant desire, but a kind of sickness.

Fernweh was described by Germans such as famous writer Johan Wolfgang von Goethe decades prior to its emergence, but it first appeared in literature in 1835 in a travel account written by Hermann Prince of Pückler-Muskau. The nobleman and landscape gardener wrote that he “never suffers from homesickness (Heimweh) but rather from Fernweh” (Fernweh – Glasmuseum, n.d.). The word has since risen in popularity. Though Germany has a long history of travel and wanderlust that has enriched its vocabulary, Fernweh as a concept is not constrained to any one country or tradition.

Scholars, poets, and artists around the world articulate Fernweh in diverse and creative ways. Psychologist Zachary Beckstead argues that the interplay between internal and external worlds makes possible the “sense of the extraordinary” that accompanies travel. The process of travel and pilgrimage is central to the “developmental self-becoming process.” He writes “punctuated experiences of the novel, the desire to be fascinated and even frightened, co-mingle with a longing for the comfortable and familiar” (Beckstead, 2010, p. 392). Poet Elizabeth Bishop writes in Questions of Travel, “Is it lack of imagination that makes us come / to imagined places, not just stay at home?’’ (p. 37). Danish artist Bent Holstein paints abstract, moody scenes from his studio in Copenhagen inspired by travels in the tropics (Bent Holstein Exhibition „FERNWEH”, n.d.). He describes Fernweh as the main driver of his work.

Upon arrival in Rome in the Fall of 1768, Goethe writes in his “Italian Journey”, “My longing to see this land was more than ripe. Only now that it is satisfied have my friends and fatherland truly become dear to me again. Now I look forward to my return” (p. 830). Travelers know this push and pull well. Even under the most ideal circumstances, this “silver lining of melancholia” shows up in the longing for home or far away. Despite this discontent, we still subject ourselves to the in-between. As Beckstead (2010) writes, “we build our worlds in the movement between ‘home’ and ‘far away’” (p. 391). Fernweh and Heimweh help put a name to that experience.

References

Beckstead, Z. (2010). Commentary: Liminality in Acculturation and Pilgrimage: When Movement Becomes Meaningful. Culture & Psychology, 16(3), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X10371142

Bent Holstein exhibition „FERNWEH”. (n.d.). Daugavpils Mark Rothko Art Centre. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from https://www.rothkocenter.com/en/ekspozicija/bent-holstein-exhibition-fernweh/

Bishop, E. (2010). Questions of Travel. The Poetry Ireland Review, 101, 36–37.

Cole, T. (2015). Far Away From Here. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/27/magazine/far-away-from-here.html

Farley, D. (2020). The travel “ache” you can’t translate. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20200323-the-travel-ache-you-cant-translate

Fernweh—Glasmuseum. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2023, from http://www.glasmuseum-lette.de/en/2022/01/03/fernweh/

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. (2016). Italian Journey: PART ONE. In The Essential Goethe. Princeton University Press.

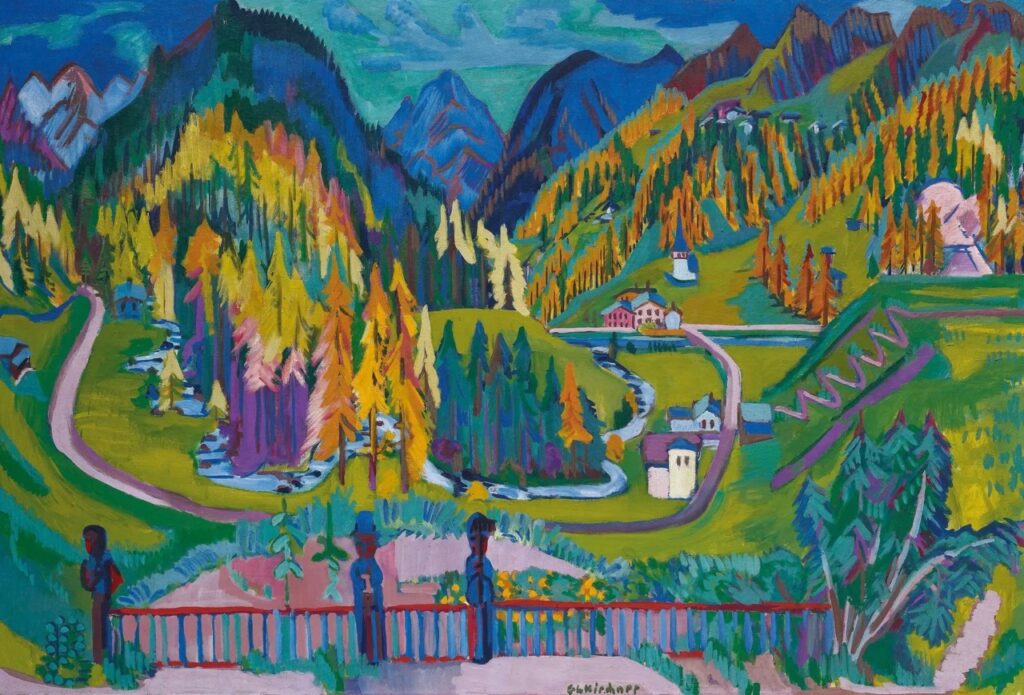

“Sertig Valley in Autumn” was painted by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in 1925. Kirchner was a founder of the Die Brücke style of German Expressionism, which emerged in the early 20th century in Dresden as a rejection of traditional artistic styles. “Brücke” translates to bridge, and these artists saw themselves as a sort of bridge between the artistic world and the bourgeois. The group became defined by bright colors and intense emotion in scenes sometimes communicating radical political views. A manifesto from Die Brücke written in 1906 states that their goal was to “achieve freedom of life and action against the well-established older forces” (

“Sertig Valley in Autumn” was painted by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in 1925. Kirchner was a founder of the Die Brücke style of German Expressionism, which emerged in the early 20th century in Dresden as a rejection of traditional artistic styles. “Brücke” translates to bridge, and these artists saw themselves as a sort of bridge between the artistic world and the bourgeois. The group became defined by bright colors and intense emotion in scenes sometimes communicating radical political views. A manifesto from Die Brücke written in 1906 states that their goal was to “achieve freedom of life and action against the well-established older forces” (