DICKINSON COLLEGE COMMUNITY STUDIES CENTER GLOBAL CLOTHESLINE DOCUMENTARIES

The Global Clothesline Project is a visual display that bears witness to violence against women, and their experiences with healing and community building. As a grassroots movement, It extends work begun in Cape Cod in the early 1990s and builds upon Dickinson College’s Pennsylvania Clothesline Project that interviewed women about the making and the meaning of their shirts. Professor Susan Rose, colleagues, and students have facilitated Clothesline Projects among diverse women in the U.S., Venezuela, Bosnia, the Netherlands, and Cameroon

![]() Community Studies

Community Studies

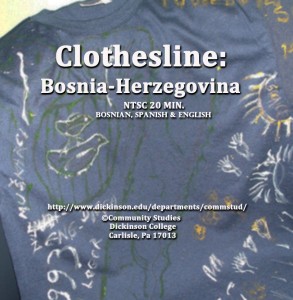

Clothesline: Bosnia-Herzegovina features interviews that Shannon Sullivan ‘09 conducted with women who were part of a witness protection program in Bosnia. It also includes a conversation with Mersida Camdzic, a Bosnian woman now living in Central Pennsylvania, who in the process of helping with the translation, decided to tell her own story. The two-part documentary (total running time 20 minutes) was co-produced by Manuel Saralegui ‘09, Shannon Sullivan ‘09, Gabriela Uassouf ‘10, and Professor Susan Rose (Tri-lingual in English, Bosnian, and Spanish).

Clothesline: Bosnia-Herzegovina features interviews that Shannon Sullivan ‘09 conducted with women who were part of a witness protection program in Bosnia. It also includes a conversation with Mersida Camdzic, a Bosnian woman now living in Central Pennsylvania, who in the process of helping with the translation, decided to tell her own story. The two-part documentary (total running time 20 minutes) was co-produced by Manuel Saralegui ‘09, Shannon Sullivan ‘09, Gabriela Uassouf ‘10, and Professor Susan Rose (Tri-lingual in English, Bosnian, and Spanish).

Clothesline: Venezuela, In the summer of 2007, Susan Rose and Gabriela Uassouf ’10 organized three Clothesline projects in both the urban barrios and rural areas in the state of Lara, Venezuela. The 12 minute documentary produced by Uassouf and Rose features women and girls of all ages making shirts and telling their stories of violence, awareness, and healing. Bi-lingual in Spanish and English.

Clothesline: Venezuela, In the summer of 2007, Susan Rose and Gabriela Uassouf ’10 organized three Clothesline projects in both the urban barrios and rural areas in the state of Lara, Venezuela. The 12 minute documentary produced by Uassouf and Rose features women and girls of all ages making shirts and telling their stories of violence, awareness, and healing. Bi-lingual in Spanish and English.

The original 1995 Clothesline Documentary (produced by Lonna Malmsheimer and Susan Rose) features interviews with women about them making and the meaning of their shirts (53 minutes). CLOTHESLINE is a 53 minute documentary video based on interviews with women who contributed artwork to the central Pennsylvania Clothesline Project. The Clothesline Project, organized in conjunction with the national project based in Massachusetts, invited women to construct T-shirts that expressed not only the violence they suffered but also the healing and recovery they were experiencing. Since the hanging of over 90 T-shirts in January 1993 in the local area, a number of shirts were sent to Vienna, Austria as part of the United Nations exhibit which raised concerns about violence against women as a human rights issue and to Washington, D.C. for the national exhibit of over 5000 shirts, and to the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. This grass-roots project has particular significance to women in Pennsylvania, but also to women nationally and internationally.

White shirts (contributed by family or friends) represented women who had been killed, blue or green shirts were made by victims of childhood sexual abuse or incest, red shirts were constructed by victims of rape, and purple shirts by women who had suffered violence because of being lesbian. The women drew upon different images and materials to portray the abuse and healing they experienced: black felt and burlap hearts, pieces from childhood dresses, broken candles, ripped out hearts, lace daggers, and photographs of graduation day. The video brings together the images created and the women’s own testimony about both the significance of those images to them and about their experience in constructing the artwork. The choice of the burlap fabric, for instance: “I just feel like I have a very rough heart. This is the wound, the incest…. And the little hammers are what I’ve used all my life to beat myself into not allowing me to be me.” A striking red shirt, cut up the middle by an artist’s rendering of a knife: “When I made the shirt I kept feeling so naked…. I better put something else on it. I better put something on the back. The shirt, it seems too stark. And then I realized that’s how I felt…. I was feeling naked, and I was feeling very vulnerable and very fragile and very exposed in thinking about the whole thing, and making the image, and bringing the image out into the public’s eye… I think that’s the tight rope that needs to be walked…. It’s a very empowering situation to go ahead and act, even in the midst of that kind of vulnerability.”

Interviewees also speak directly to the public about their victimization and show considerable insight concerning current media treatments (both fictional and nonfictional) of violence against women. They show themselves as exquisitely sensitive to the publicly reported debate about the effects of abuse, delayed and immediate, about the vulnerability of memory and the reliability of repressed memory. They have strong ideas about how the institutions of society relate to violence against women and are particularly eloquent about the abuse of children. “Breaking silence” through visual expression is seen by the survivors as both an act of caring for the self, a step in healing, and as a gift to others, as a way of supporting other victims and of forcing perpetrators and bystanders to confront these issues.

Discussions following the screening of Clothesline have focused on various aspects of survivor narratives, the cultural rhetoric of violence against women, the interactive process of interviewing and its relationship to therapeutic techniques and processes, “the discourse of embodiment.” In other cases, the discussions have focused on video as a medium of collection, compilation, and synthesis, and the problematics of production values.

At the Fourth World Women’s Conference in Beijing, domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in particular were discussed from a cross-cultural perspective. A conversation among women from Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, New Zealand, Australia, the U.S., India, China (and other countries) raised various questions, including:

1. To what extent does incest, as an act of violence against an individual girl or woman, also act as political disempowerment of girls and women in general? Does incest or other acts of violence act in similar ways across cultures?

2. What are the connections/differences among the kinds of violence described here and those women in other cultures and societies experience? What are the similarities/differences among the kinds of conditions likely to generate violence against women?

3. The women in this video are giving voice to the violence committed against them, thus taking back some of the power stolen from them. In what ways do women cross-culturally resist violence? To what extent is “breaking silences” important for women in other cultures? What forms does this take?

4. “Clothesline” raises issues not only about violence against women, but also about feminist activists and scholars using video-making as the basis for their work. To what extent are women internationally using video as a means for generating knowledge, for reclaiming power of the media?