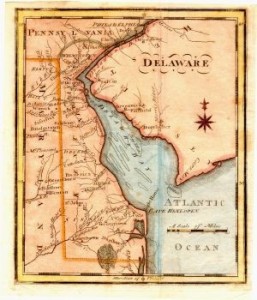

George Read had many political strengths and used them in his quest to rise and become a leader in the development of the United States. However, his name is not recognized by most. In fact, only his contemporaries and Delaware residents recalled his significant contributions to the founding of the United States. At the Delaware Constitutional Convention in 1776, he was “the most influential delegate in the state constitutional convention” (Munroe). He rose to political standing as a self-made man, using all the resources in his path to success.

Read was born in Cecil County, Maryland on September 18, 1733. He was the son of the Irish immigrant John Read, a planter from Dublin, Ireland, and Mary Howell, an immigrant from Wales. His parents were not well-educated and his family-name was not recognized. Read was determined to bring pride to his family name. Unlike his parents, he received a classical education at the Reverend Francis Allison’s academy in New London and at age fifteen studied law in Philadelphia (Monroe). The education would not have been possible without the support of Reverend Allison, his caretaker while in New London. His law education was a major asset that aided his knowledge of the judiciary. In 1780, he served as a judge in Delaware. Not only did he read over legal documents carefully, but he also saw the practical applications of them: how they directly impacted the people. Those abilities made people recall him as a “deep-read lawyer and versed in special pleading, the logic of law” (Read, 15). In 1797, he compiled the two-volume collection of the Laws of Delaware.

He was called a Founding Father because he was one of the state delegates who signed the

Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the US Constitution; thus he assisted large-scale government decisions. However, the majority of his political occupations focused on issues at the state-level, small-scale government decisions, rather than at the national-level. For example, the main reason he supported the Alexander Hamilton’s notion of a strong central government was that the government would regulate the power of larger states. Delaware was a small state; hence if the states gained control of the government, larger states would most likely receive the upper-hand in establishing legislative measures.

Read started out as a man who was concerned with the public impact of government decisions. During the Revolutionary Period, he was the “leader of the moderate party in Delaware” (Monroe) and “member of the Delaware Committee of Correspondence” (Read, 330). He was a key individual involved in the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1765 and “secured compliance with Philadelphia nonimportation agreements in 1768” (Monroe). He was said to be “active in patriotism” (ushistory.org), but he did not want to fight off the British. Similarly to his colleague, John Dickinson, he did not have a desire to break free from the Royal Crown. The British structure provided a platform for stability in 18th century America while the country

learned to govern itself. Additionally, he respected the Royal Crown, since he thought Britain was a well-established nation and was treating the American colonies properly. The British knew Read was a loyal supporter to their political policies. They even offered him an office position under British government in which they promised him a share in the financial benefits (Read, 21). However, this position came at a time when Read was beginning to realize that the disturbances between the colonies and the Royal Crown were problematic. The British began to repress the rights of the American people and pass taxes without the consent of the people. As a result, Read refused the British offer. His patriotism and integrity overpowered the potential economic rewards from the job offer. Although patriotism was not the main reason he made his decision, it was due to protecting his reputation and character.

According to historian Gordon Wood, 18th century character was a concern of the Founders, which meant they were “preoccupied with their honor or their reputation, or, in other words, the way they were presented and viewed by others” (Wood, 23). Read’s actions do not follow Wood’s definition of character, since Read’s actions were private. It can be debated that Read fits the mold of a modern character, since he seems to have “inner personality that contains hidden contradictions and flaws” (Wood, 23). Read does not have any memorable speeches or public announcements throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Even as a representative at the Annapolis Convention (1786) and Philadelphia Convention (1787), he did not make any noteworthy remarks. In order to understand his position on political topics, the information was gained through letter exchanges. These letters revealed Read’s perception of the government’s direction. During the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention (1787), Read wrote a Letter to John Dickinson that focused on smaller state’s rights. He proposed that larger states should be watched over carefully or else they will potentially suppress the rights of the smaller states. It can be argued that his character was achieved in the state of Delaware, but would not be identified by everyone.

His lack of character explained how he shifted from public to private regarding government decisions. First, he never verbally expressed that he was against the new independence resolution devised by the other delegates on July 2, 1776. He essentially “Thought it (Declaration) premature, the people, and especially many of his own constituents, not being ripe for it” (Read, 334). Congress was not giving the citizens enough of an advanced notice about the changes that would happen in the government. He even criticized in a published 1871 newspaper article that the document “did not have a Table of Contents nor an Index” (Life and Correspondence of George Read Signer of the Declaration of Independence). Despite his inward objection, at the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, he along with fifty five other delegates approved the document (Monroe). He concluded he did not want to risk his reputation on account of political disagreement. He would lose all his supporters and followers that have been by his side. His intentions were to maintain good character, yet his actions did not match those intentions. He kept his opinions hidden and made his political decisions on behalf of Delaware. John Dickinson voiced his disagreement of the new independent resolution; he did not even sign the Declaration of Independence. Dickinson showed adequate character, since he had an image publicly known. Colonel Bedford questioned Read’s character.

Even though Read did not demonstrate good character he did possess the other qualities of the Founders including disinterestedness, republicanism, and virtue. Read was a follower of moral code and classicism. He was a man of honor, he would never break a rule. Additionally, he was know for his understanding in human nature similar to Benjamin Franklin. Other Founders knew of his high honor and sought him out for advice on their own policies. Dickinson asked him in a letter for advice on a land ownership issue (Dickinson Archives). He became disinterested, since in 1779 he temporarily retired from politics, but in 1780 he was appointed to be the “Judge in the Court of Appeals” in Delaware (ushistory.org). He helped create Delaware legislative policies. His focus on state politics rather than federal politics caused him to not build up his reputation. He was an important founding father, but not remembered.

References

Dickinson, John. Letter to George Read. Wilmington, VA: 16 December 1785. Dickinson College Archives.

Munroe, John. “Read, George“; http://www.anb.org/articles/01/01-00772.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000. Web. 7. November 2014.

Munroe, John. Nonresident Representation in the Continental Congress: The Delaware Delegation of 1782. The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1952): pp. 160-190. Web. 1. November 2014.

“Life and Correspondence of George Read a Signer of the Declaration of Independence” with notices of some of his contemporaries. Historical Magazine Post Jan 1871: Print.

Read, William. Life and Correspondence of George Read A Signer of the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Company, 1870. Print

Read, George. Letter to John Dickinson. Philadelphia: 21 May 1787. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/letter-to-john-dickinson/

Wood, Gordon. Revolutionary Character What Made the Founders Different. New York: Penguin Group, 2006. Print

Received, thanks