Since the very beginning of the United States of America there was an incredibly divisive issue at the heart of the nation. A nation built upon the ideals of equality and freedom was also built using the institution of slavery, an institution exemplifying the traits of cruelty, subservience, and captivity.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the tension between the two regions of the United States grew until it could no longer be contained on April 12, 1861, when confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter.[1] Through the first 2 years of the war, Lincoln refused to make the war effort about the emancipation of slaves. While some cases of contraband act and confiscation helped free some slaves, there was no sweeping legislation to free most of the slaves in the nation.[2] However, after the Battle of Antietam the President put forth the Emancipation Proclamation which freed all the slaves within the confederate states.[3] Once it was clear the war is being fought for the freedom of African Americans across the union Frederick Douglas steps in front of a crowd at Rochester NY on March 2, 1863. While this speech appeared to be hopeful and inspirational to rally support behind the northern cause, Frederick Douglas truly feared that a war won without the help of the African American race would invalidate a large portion of the work done to develop the equality of races.

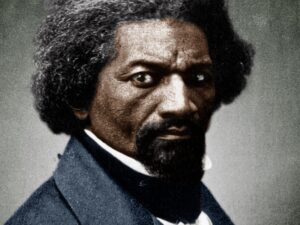

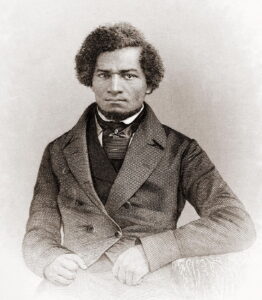

Frederick Douglas, a former slave who turned into an incredibly influential abolitionist, gave an essential speech to win over the hearts of a powerful fighting force. Throughout the speech he developed his argument with a historical base. In the very beginning of the speech, he emphasized how and when the war between regions was started. Frederick Douglas highlighted the firing on Fort Sumter. Within that first paragraph Douglas claimed that he predicted that the final cause of the war would be to end the institution of slavery saying that “I predicted that the war then and there inaugurated would not be fought out entirely by white men”.[4] He then moved on to the politics of Emancipation and his pressure to manufacture a new cause for the war. Within the speech Frederick Douglas claimed that “I have implored the imperiled nation to unchain against her foes, her powerful black hand”. [5] In this excerpt he is demonstrating his support for a cause of war to be built out of equality for all men no matter the race so that the African populous in America may fight upon the unions side. Then the speech shifted towards a call to action. Douglas changed his tone to compel people into action and fight for their basic rights to be protected. He does this by shaming the “weak and cowardly men” while spotlighting the ideas of the “brave men” fighting with the union forces.[6] Douglas wrapped up the speech by imploring the listeners to think about not only themselves but other slaves, their children, and their future within the United States of America. Through these ties Douglas created the nature of the speech to be one of a call to action. Frederick Douglas, a powerful orator successfully conjures up the feelings of hope

and necessity which madee this speech one of an inspirational message with an incredibly powerful effect on the African American contingent in Union at that time. Douglas uses a multitude of powerful words such as “imperiled nation”, “unchain”, and “great struggle” to stir up the emotions and create support for the northern cause showcasing the true nature of the speech.[7]

Frederick Douglas, one of the most famous orators and former slaves of all time, was not always destined for greatness. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland in 1818 as a slave.[8] He never knew either of his parents. At 8 years old he was loaned out to a client in Baltimore. Although he was not allowed to attend school in Baltimore, Douglas first began to learn to read and write on the streets of Baltimore.[9] He read a multitude of sources however the most prominent piece of literature that influenced his actions was a book called “The Columbian Orator”.[10] This book was filled with passionate speeches and scintillating debates. When he arrived back to the eastern shore of Maryland, Douglas rebelled and educated the other slaves on the plantation to such a degree that he was sent back to Baltimore.[11] On his return trip to Baltimore, he met Anna Murray, a young free African American woman, who facilitated his escape to freedom by buying him a train ticket.[12] Once free, Frederick Douglas became the man

that he is known for today. He gained fame as a powerful orator pushing for the abolition of slavery and eventually developed his own newspaper, “The North Star”.[13] When the Civil War broke out, he repeatedly pushed Abraham Lincoln to change the true nature of the war from one of national unity to a war fought over the abolition of slavery. Douglas helped galvanize the support of the black populous to support the Union war effort and ultimately led to the defeat of the Confederate states. Throughout Frederick Douglas’s youth he felt the hardships of being a slave. This experience made him determined to put an end to the awful institution by any means possible. For the rest of his life, he was committed to establishing a better future for his children and wife. Douglas died in 1895 at the age of 77 due to a heart attack.[14]

When the Civil War started in 1861, the north was extremely confident in the fact that it would be a quick and decisive war. However, within the first two major battles of the war that idea would soon prove to be a fantasy. In the battles of Bull Run and Wilson Creek in 1861, the union forces were soundly defeated which signaled that the war would drag on for many years.[15] While the Union forces had greater men and manufacturing fueling them, they had to capture and occupy land whereas the Confederate forces simply had to defend. This difference in military objectives led to an increasing number of defeats for the Union army. A

lack of major victories in the eastern theater was quelling the excitement of war and damaging the northern morale. By September 1862, the Confederate states seemed to be winning the war so far. Frederick Douglas alluded to this by pointing out that the effort to incorporate the black citizens of the Union should have started sooner.

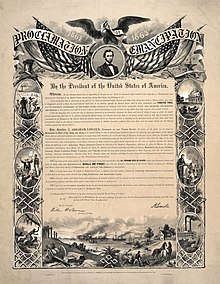

Lincoln was extremely clear in the intentions of the war at the outbreak of the Civil War: to maintain the Union. The balance of states that held up the Union position was too vital to potentially sever. However, as the time slowly dragged on, the importance of emancipation grew increasingly distinct due to a lack of major military victories for the northern states. Within the speech, Douglas alluded to all the times he petitioned the President to change the focus of the war from one of unity to one of equality. However, Lincoln was firm in his judgement to wait a while longer which can be seen in Lincoln’s response to Horace Greeley, an abolitionist and editor of the New York Tribune and colleague to Douglas, in August of 1862 where he states, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or destroy Slavery”.[16] Even with this façade to the American public, Congress and Lincoln had already begun to slowly chip away at slavery. Beginning with the Contraband act and Confiscation acts in 1861, the northern armies began to become a haven for blacks escaping the southern war effort.[17] While these acts were justified because they hurt the southern war effort, they also began the slow adjustments necessary for emancipation.

A staggering war effort and a lack of decisive policy measures made the President a relatively unpopular man in Washington D.C. However, these two issues would be combined and solved through the same action: The Battle of Antietam. The Battle of Antietam would culminate to be the

bloodiest day in American history in which 23,000 men were killed or wounded on the battlefield.[18] It ended the Confederate armies first foray into union territory and was one of the first major victories for the northern states along the eastern seaboard. President Lincoln saw this as the most apt time to release a draft he had been working on for months: the Emancipation Proclamation. This revolutionary action was an executive order set to free the slaves within the southern states. The abolitionists were overjoyed by the news of a first great step towards the ending of the fight they have dedicated their lived towards. Frederick Douglas commented on the proclamation in a speech in October of 1862, “But read the proclamation for it is the most important of any to which the President of the United States has ever signed his name”.[19] Now less than 3 months after the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglas was once again urging people to join the war and support the northern cause with the greatest possible sacrifice a man can make.

In the speech “Men of Color to Arms” Douglas portrayed the tone of an inspirational speaker. He created feelings of hope and courage to encourage people to fight for a cause bigger than themselves. However, when you consider the context and message of the speech, you will find that Douglas is also speaking out of fear. This is not a fear of the southern state’s military or political power. It is a fear born out of the attitudes of the northern populous, congressmen, and Union soldiers. Douglas feared that a war won without the help of the African American race would invalidate a large portion

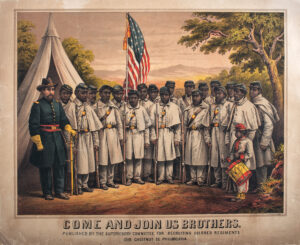

of the work done to develop the equality of races. This fear from Douglas is not irrational. In February of 1864, black soldiers stationed in Zanesville, Ohio were tormented by racial slurs and attacked.[20] Racist opinions permeated throughout the entire nation, north or south. The lack of an established black regiment throughout the army would only have developed the ideas of the American population of 1860s that equality was unrealistic as blacks would always be less than whites. Even union soldiers fighting on the front lines held these same sentiments. For example, John Cuddy, a private in the Union army, wrote home to his parents claiming, “Dear friends this ware is an auffel thing fighting for ngroes now is a bad thing”.[21] This demonstrates the direct disconnect between the grand visions of the abolitionists and the common person. Political power in the north was also a major obstacle which could only be overcome by demonstrating that the blacks of American had also given all they could to defeat a common enemy. The Northern Democrats were an obstacle which could have easily endangered the building of equality between races. Horacio Seymour, a northern democrat commented on the Emancipation Proclamation by calling it “unconstitutional”.[22] Only military success would help begin to turn opinions.

Frederick Douglas, a slave, an abolitionist, a father, and an orator, looked to turn the tide in both the efforts of the Civil War and the war against the racist outlooks. He aimed to complete both tasks with the speech in Rochester, NY named “Men of Color to Arms”. Within this speech he projected a confident and inspirational tone while also looking to prevent the invalidation of the

abolitionists work in the future. With the help of influential speakers like Frederick Douglas, enrollment by African Americans swelled to nearly 200,000 in all the armed forces. These armed forces served with distinction quelling any concerns about their ability on the battlefield.[23] Sixteen black soldiers were awarded the medal of honor and helped tear down the wall of racial prejudice.[24] While the fight to end the war against racial discrimination continues today, the fight may have not been started had it not been for people like Frederick Douglas and speeches like “Colored Men to Arms”.

[1] “Civil War Timeline,” National Park Service, last modified March 5, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/civil-war-timeline.htm

[2] Louis Masur, The Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 39.

[3] “Civil War Timeline”

[4] “FREDERICK DOUGLASS, MEN OF COLOR, TO ARMS (1863),” House Divided Project at Dickinson College, last modified n.d.,

https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/teagle/texts/frederick-douglass-men-of-color-to-arms-1863/

[5] “FREDERICK DOUGLASS, MEN OF COLOR, TO ARMS (1863),”

[6] “FREDERICK DOUGLASS, MEN OF COLOR, TO ARMS (1863),”

[7] “FREDERICK DOUGLASS, MEN OF COLOR, TO ARMS (1863),”

[8] “Frederick Douglass,” National Park Service, last modified July 24, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/frdo/learn/historyculture/frederickdouglass.htm

[9] “Frederick Douglass”

[10] “Frederick Douglass”

[11] “Frederick Douglass”

[12] “Frederick Douglass”

[13] “Frederick Douglass”

[14] “Frederick Douglass”

[15] “Civil War Timeline”

[16] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States: 1492 – Present. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003), 190.

[17] Zinn, People’s History of the United States, 190.

[18] “Antietam: A Savage Day In American History,” npr, last modified September 17, 2012, https://www.npr.org/2012/09/17/161248814/antietam-a-savage-day-in-american-history

[19] “Frederick Douglass Project Writings: Emancipation Proclaimed,” University of Rochester, last modified n.d., https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4406

[20] Zinn, People’s History of the United States, 195.

[21] “John T. Cuddy to John H. Cuddy, January 16, 1863,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32755.

[22] Masur, The Civil War, 43.

[23] “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War,” National Archives, last modified September 1, 2017, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

[24] “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War”