Wood, American Revolution, Chapter 1 –Origins

- DEMOGRAPHICS

- Population in North American colonies (22, then 25) doubles between 1750 & 1770

- Diversity in migration and expansion into backcountry = friction

- ECONOMICS

- Nearly half of English shipping engaged in “American” trade by mid-century

- 19 out of 20 American colonists engaged in agriculture but consumerism rises

- POLITICS

- After 1763, British attempt to end period of “salutary neglect”

- George III (reign 1760-1820) battles with Whigs in Parliament

In his short book on The American Revolution, historian Gordon Wood offers a series of powerful insights about the nature of the British Empire in the eighteenth century. First, it was about much more than the so-called thirteen colonies along the Atlantic coast of North America. To begin, Wood points out that there were 22 British colonies in the Western Hemisphere by 1760, and the eighteenth-century empire , which he terms “the greatest and richest empire since the fall of Rome,” quite literally “straddled the world” (4). Yet by the middle of the eighteenth century, it was also a wildly troubled empire. If there was one colonist in British North America who seemed to embody both the perils and promises of the British imperial system, it might have been Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). Today, we consider Ben Franklin as the ultimate symbol for the American spirit and yet during his own lifetime, Franklin was often regarded as more British than American, and even after the War for Independence began, the diplomat and renowned scientist Franklin was a uniquely cosmopolitan figure.

, which he terms “the greatest and richest empire since the fall of Rome,” quite literally “straddled the world” (4). Yet by the middle of the eighteenth century, it was also a wildly troubled empire. If there was one colonist in British North America who seemed to embody both the perils and promises of the British imperial system, it might have been Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). Today, we consider Ben Franklin as the ultimate symbol for the American spirit and yet during his own lifetime, Franklin was often regarded as more British than American, and even after the War for Independence began, the diplomat and renowned scientist Franklin was a uniquely cosmopolitan figure.

Maps like the representation to the left, or the one above right, offer shorthand ways to contextualize the eighteenth imperial system.

Maps like the representation to the left, or the one above right, offer shorthand ways to contextualize the eighteenth imperial system.

18th-Century Individualism

“What then is the American, this new man?”

–Crèvecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer (1782)

- Consumerism

- Currency & credit

- Trade

- Imperial politics

- Religious Awakening

- Slavery

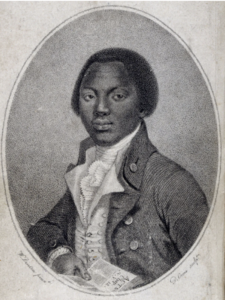

African Slave Trade

“…The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave-ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, which I am yet at a loss to describe, nor the then feelings of my mind. When I was carried on board I was immediately handled, and tossed up, to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I was got into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, which was very different from any I had ever heard, united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country. When I looked round the ship too, and saw a large furnace of copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate, and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little, I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and long hair?”

- Equiano, Interesting Narrative, Knowledge for Freedom seminar (Dickinson)

- Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, 1514-1866 (David Eltis / Emory)

- Alexander Falconbridge, An Account of the Slave Trade (1788)