Defining the “Mission of the War”

In November 1863 in his now-famous Gettysburg Address, Lincoln defined what he called, “the great task remaining before us,” in the Civil War, namely, “that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” These key phrases were not entirely original to Lincoln. In some ways, that was the point. They were intended to be evocative and unifying for northerners of all political stripes and for any loyal southerners

But it was notable that Lincoln did not utter the words “emancipation” or “abolition” in his statement of national purpose. Thus, in January 1864, two leading radical voices, Frederick Douglass and Anna Dickinson, responded with a more explicit version of the war’s meaning. On January 13 in New York, Douglass reiterated his view that the “Mission of the War” was an “Abolition war” and that there could be no peace but an “Abolition peace.” He openly criticized Lincoln for not realizing this truth, but conceded that the president had made some “progress” since his disappointing inaugural address in March 1861. Celebrated orator Anna Dickinson, age 21, spoke just a few days later at the US Capitol building in Washington DC regarding what she termed, “The Perils of the Hour.” Dickinson offered more praise for Lincoln than Douglass had, but she, too, considered his words and promises during the war to have lacked power. For example, speaking of the Union dead at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Dickinson asked, “But for what did they fight and for what had they died?” Then she provided a version of Lincoln’s answer from Gettysburg: “In order that, in the language of the President, ‘good government might not perish from the earth.'” However, clearly such a vow was not enough for Dickinson, who viewed the reality of the American Revolution as far from perfect. She added with deliberate emphasis:

In 1776 our independence was asserted, but 1861 was the beginning of liberty. To-day we were fighting an oligarchy built upon the degradation of four millions of black men and eight millions of white men. Liberty threatened, had seized and wielded the only weapon of attack or defence – liberty. It was for slavery they were contending, we for liberty, and God save the right!

- Consider close readings of Douglass’s Mission of War speech or Dickinson’s Perils of the Hour speech

- Consider a close reading of Sam Wilkeson’s original newspaper article about Gettysburg, which included the phrase, “second birth of freedom in America”

Election of 1864

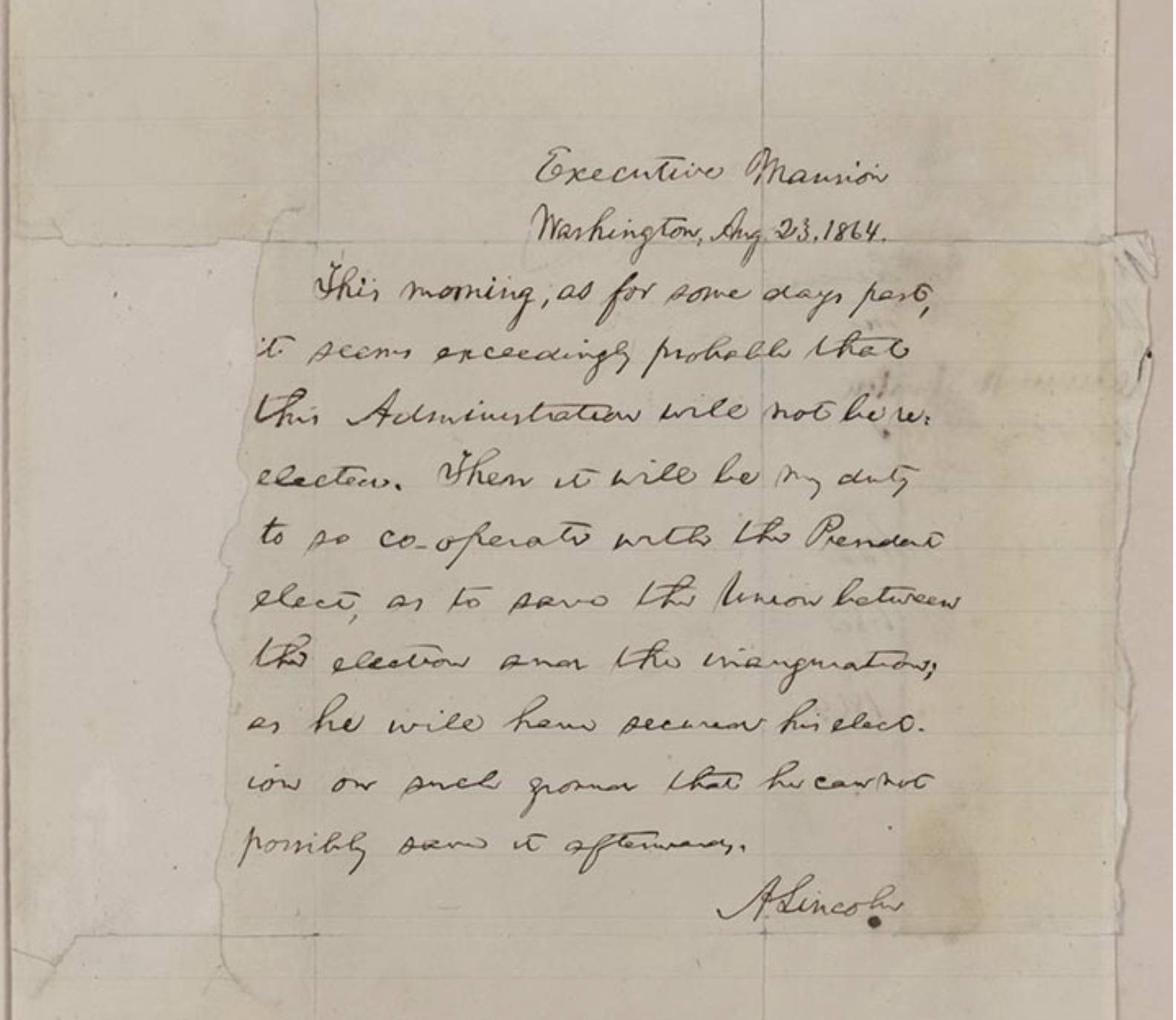

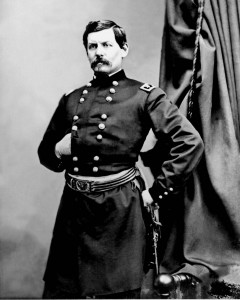

Abraham Lincoln was re-nominated for president in June 1864 by the newly organized National Union Party with Democrat Andrew Johnson as his running mate. Yet on Tuesday, August 23, 1864, Lincoln wrote a secret memorandum that began, “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected.” He then proceeded to sketch out a plan for cooperation with the next President-Elect in the event of his own defeat. He did not know for sure at that time, but he anticipated that his successful partisan opponent might be General George McClellan, who would in fact be nominated by the Democrats in late August 1864 as their nominee for president. Louis Masur casts the so-called “blind memorandum” as a sign that Lincoln “came to believe that he would lose the election in November” (p. 68), but he doesn’t explain what the embattled president thought he was accomplishing by putting these sentiments down on paper. What do you think?

Abraham Lincoln was re-nominated for president in June 1864 by the newly organized National Union Party with Democrat Andrew Johnson as his running mate. Yet on Tuesday, August 23, 1864, Lincoln wrote a secret memorandum that began, “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected.” He then proceeded to sketch out a plan for cooperation with the next President-Elect in the event of his own defeat. He did not know for sure at that time, but he anticipated that his successful partisan opponent might be General George McClellan, who would in fact be nominated by the Democrats in late August 1864 as their nominee for president. Louis Masur casts the so-called “blind memorandum” as a sign that Lincoln “came to believe that he would lose the election in November” (p. 68), but he doesn’t explain what the embattled president thought he was accomplishing by putting these sentiments down on paper. What do you think?

- Consider a close reading of documents from the 1864 election, such as the blind memorandum, or the political party platforms, or some political cartoons from the 1864 campaign

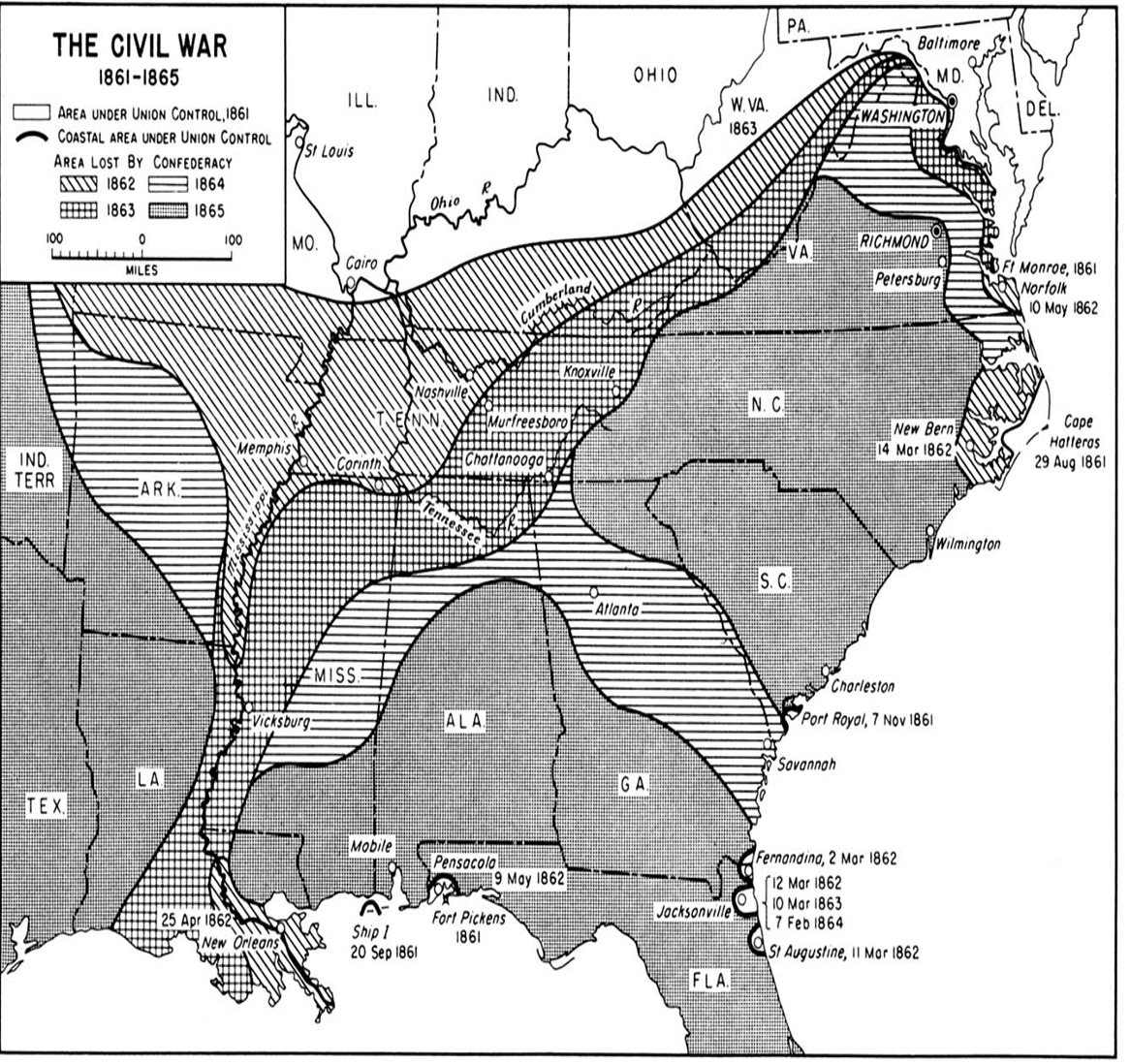

Hard War and Sherman’s March (Fall / Winter 1864)

“We cannot change the hearts of those people in the South … but we can make war so terrible … [and] make them so sick of war that generations would pass away before they would again appeal to it.” (Quoted in Masur, 73)

- Consider a close reading about Black leaders meeting with Sherman in 1865 or his subsequent Special Field Order No. 15 promising them land from reclaimed plantations along the Atlantic coast

From Carlisle to Andersonville

–Consider a close reading of John Taylor Cuddy’s letters