Louis Masur begins the final chapter of his book, The Civil War: A Concise History (2011) with a powerful opening line: “On January 11, 1865, Robert E. Lee wrote a letter that would have been unthinkable three years earlier.” The reference is to Lee’s endorsement for the use of black troops, a move that most Confederates had previously resisted. But as Masur points out, the belated decision, finally approved in March 1865 (just weeks before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox) demonstrated “perhaps” the “strength of Confederate nationalism” (76). In other words, the question had always been which motivated Confederates more, a desire for their own political rights or the continuation of slavery? In recent years, there has been an explosion of controversy over the particular subject of “Black Confederates.” The debate mainly concerns whether they existed at all before the spring of 1865. Here is one image frequently circulated over the Internet:

But here is the original version of the same image, unaltered, showing that these alleged “Black Confederates” from 1861 were actually Union soldiers in training near Philadelphia in 1864.

Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite thoroughly dissect the manipulation of this image in their post, “Retouching History: The Modern Falsification of a Civil War Photograph” (2005).

Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite thoroughly dissect the manipulation of this image in their post, “Retouching History: The Modern Falsification of a Civil War Photograph” (2005).

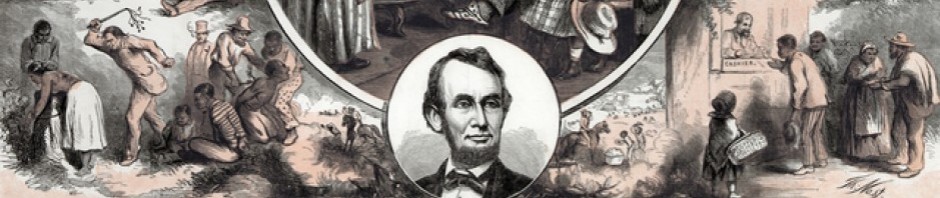

Altering images is not just a modern-day phenomenon. Print-makers and illustrators in the nineteenth-century were just as creative and calculating. In fact, the banner image from this course website provides a good example of what might be called pre-photoshop photoshopping undertaken by a commercial printer in Philadelphia following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. Here is what the image looked like that year:

Yet here is what the original illustration looked like in January 1863 when Thomas Nast first drew it for Harpers Weekly:

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

Sometimes significant changes are also sometimes accidental rather than intentional. Here is a different image that was misdated for years as 1864. Yet this is actually a detail from a photograph taken in Washington DC in November 1865. Students in History 117 should be able to explain why that seemingly small mistake matters quite a bit.

Sometimes significant changes are also sometimes accidental rather than intentional. Here is a different image that was misdated for years as 1864. Yet this is actually a detail from a photograph taken in Washington DC in November 1865. Students in History 117 should be able to explain why that seemingly small mistake matters quite a bit.

Believe it or not, it’s also possible to enhance images by altering them. Here is a photograph taken at Fort Sumter on Friday, April 14, 1865. That was a special day for the Union coalition –a kind of “mission accomplished” moment as Col. Robert Anderson returned with a delegation of notables, including abolitionists like Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and William Lloyd Garrison, to raise the American flag once again over the fort in Charleston harbor where the Civil War had begun almost exactly four years earlier.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

That’s Rev. Henry Ward Beecher speaking on the afternoon of Friday, April 14, 1865, from what he called “this pulpit of broken stone.” Originally, scholars, using magnifying glasses, thought that William Lloyd Garrison was perhaps seated on Beecher’s left.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

It was obviously a moving, reflective moment for Garrison, one captured in this detail image above from right after the ceremony and by the little known story of his visit the following morning to see the grave of secessionist icon John C. Calhoun. You can read more about this episode here and here. Sometimes people are surprised by the stories that slip out of public memory and don’t make it into standard textbooks. The Garrison visit to South Carolina in April 1865 is certainly one of them, but another such lost tale involves a Dickinsonian named John A.J. Creswell, who was deeply involved in the final passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, which occurred in early January 1865. Here is the image that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper to celebrate that moment.

You will notice the trio of men in the lower right hand corner, obviously prominent figures according to the illustrator. We researched them here at the college and were thrilled to discover that one of them was a Dickinsonian. It turns out that these are three congressman from the Mid-Atlantic (from left to right) Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell. We used a detail from that image for the cover of our first House Divided e-book, which profiles Creswell, a Dickinson graduate and Maryland politician who became one of the nation’s most important wartime abolitionists. Yet, he’s almost completely forgotten, not even mentioned in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Lincoln” (2012), which concerned passage of the amendment. You can download a free copy of Creswell’s biography, written by Dickinson college emeritus history professor John Osborne and college librarian Christine Bombaro, here. Ultimately, that might be the best way to “alter” images from the end of the Civil War –by seeing old stories from new perspectives.

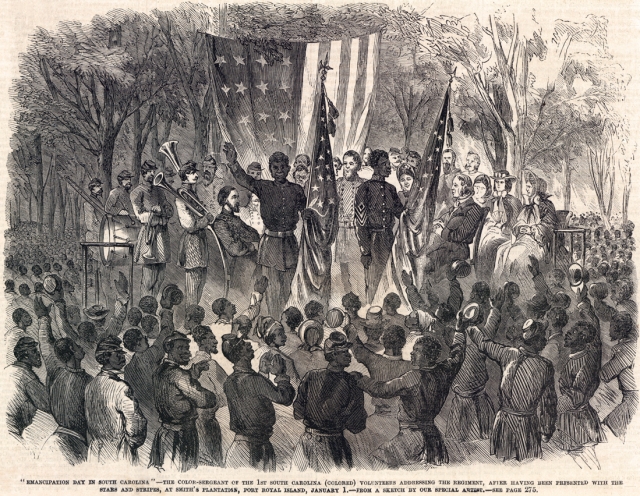

The scene at Congress on January 31, 1865 was reminiscent in some ways of an earlier scene involving a celebration of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Sergeant Prince Rivers receives the colors of the First South Carolina Volunteers, Port Royal, South Carolina, January 1, 1863 (Courtesy of the House Divided Project)

This scene in Port Royal, South Carolina is very revealing at several levels, but as a study of the end of the war, it offers a poignant window into the revealing saga of Prince Rivers, a man who arguably is the most teachable figure from the Civil War & Reconstruction era.

Prince Rivers (c. 1820 – 1887)

“Dat’s de reason I jine de soldier. I was gettin’ big wages in Beaufort, but I’d rather take less, and fight for de United States; for I believe the United States is now fightin’ for me, and for my people.” Prince Rivers quoted by James Miller McKim, August 1862

“I was told that the Government has given Land to Soldiers. If this land were given will [it] be just for the time being or will [it] be hereafter held by the Soldiers? I would like very much to know if any Part of the Mainland. If so I would like to get a piece on Mr. H.M. Stuart plantation, Oak Point, near Coosaw River.” Letter from Prince Rivers to General Rufus Saxton, November 1865

Additional resources from Emancipation Digital Classroom: