Image Gateway

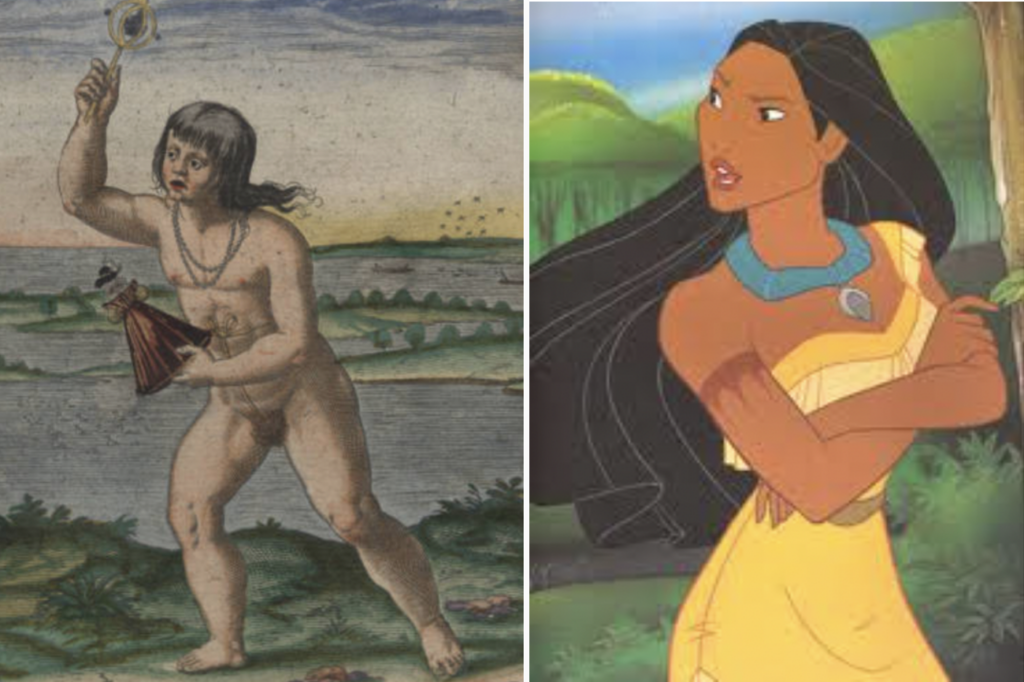

For background on the John White watercolor from 1590 (left) or the evolution toward the image of Pocahontas in the popular Disney movie (1995), see the PBS online exhibit: Pocahontas Revealed

Discussion Questions

- What context about the European imperial rivalries from the 16th and 17th centuries is most helpful for understanding the English approach to American colonization?

- How did the Protestant Reformation shape the British experience in North America?

Founding Myth #1: John Smith & Pocahontas

Chapter 2 of the Yawp online textbook barely mentions the legendary story of John Smith and Pocahontas:

John Smith, a yeoman’s son and capable leader, took command of the crippled colony and promised, “He that will not work shall not eat.” He navigated Native American diplomacy, claiming that he was captured and sentenced to death but Powhatan’s daughter, Pocahontas, intervened to save his life. She would later marry another colonist, John Rolfe, and die in England.

It turns out that there is more to the famous John Smith-Pocahontas rescue / love affair at Jamestown than either this aside or American popular culture has suggested. Many modern-day historians see the 1607 encounter as a complicated struggle between two imperial forces –both the English settlers and the Powhatan Indians. There was certainly a complex set of strategic interests at stake for Wahunsenacawh (or Chief Powhatan as the traditional literature has named him), demonstrating how he may have been attempting to use the English through the symbolic or ritual diplomacy involving his young daughter. Captain John Smith probably misunderstood what was essentially a political outreach involving Pocahontas, then approximately 12-years-old. How should historians characterize the motivations and legacies of figures such as Smith or other members of the Virginia Company, such as John Rolfe, the man who introduced tobacco to the colony and actually became Pocahontas’s husband? NOTE: all links in this paragraph go to reference pages at Virtual Jamestown.

Founding Myth #2: First Thanksgiving

The Yawp textbook seems to intentionally avoid highlighting the popular but somewhat misleading story of the first “Thanksgiving,” celebrated by Pilgrims and Wampanoag Indians (and Squanto, a Patuxet Indian, who lived among the Wampanoags) in the fall of 1621 at Plymouth. Historian Edward O’Donnell writes about that episode:

It was this fear of the Pilgrims, plus additional concerns about the threat posed by the powerful Narragansett Indians to the south, that prompted the Wampanoag leader Massasoit to make peace and establish an alliance with the Pilgrims in the spring of 1621. That spring and summer the Wampanoags taught the Pilgrims what to plant and how to hunt certain wildlife and fish. And that’s why they were invited to the first Thanksgiving in the Fall of 1621. All this ads up to a considerably more complicated version of the first Thanksgiving story than we’re used to. Had there been no Great Epidemic, it seems likely that the Pilgrims, had they survived and managed to have anything to be thankful for, would have celebrated the first Thanksgiving among themselves.

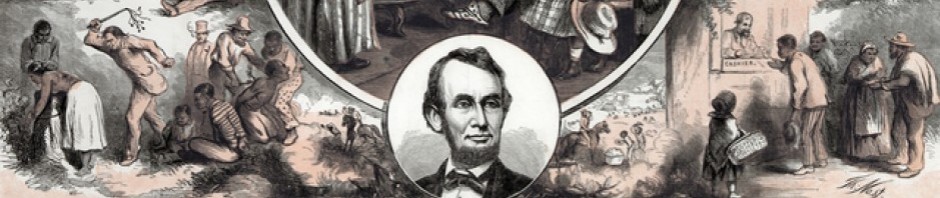

NOTE: Thanksgiving did not become a formally declared federal holiday until the American Civil War when Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation just one month before delivering his Gettysburg Address. You can read about the backstory behind that moment from this student close reading post.

Memory & Meaning

How does this musical clip from the 1995 children’s movie by Disney present a historical interpretation of Native American culture in the aftermath of the Columbian Exchange?

Handouts