By Matt Pasquali

Patricia Mackey was a college student at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh during the Kent State shootings, occurring on May 4, 1970. According to H.W. Brands book, American Dreams, on “hundreds of campuses across the country students boycotted classes and faculty suspended teaching in favor of discussions—which was to say, condemnation—of the war.” [1] Mackey remembers the immense cultural changes that took place on her campus after the shootings. “It was as though all hell had broken loose,” Mackey recalled about the day of the tragedy, “suddenly sleepy Plattsburgh campus became a hotbed of student unrest.” [2] Although Mackey’s experiences were common throughout American colleges and universities, her recollections during this time of turmoil are important because such memories can help show the drastic changes seen throughout American culture. However, memories from 40 years ago can become twisted over time. Ultimately, there were significant cultural changes seen post Kent State that Mackey lived through, keeping in mind that not everything was changed because of this event.

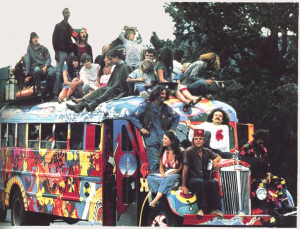

One of the most immediate changes seen during this era was among the nation’s youth. “People learned to question everything” after the shootings at Kent State. [3] “Students who had been quiet, reserved in their actions…lost the majority of their social inhibitions,” Mackey remembers. Changes in music, TV and the newly acquired drug culture became a “stronger force for expressing the public’s dissatisfaction with the status quo.” [4] The newly acquired drug culture affected everyone even if they didn’t partake in such activities. “You might not actually use marijuana or PCP…but they affected you,” recalled Mackey. Mackey noted how the drug culture caused people to “discard the traditional suit or dress of the past” and trade it in for a “psychedelic tie-dye T-shirt, bell bottom pants and sandals of the era.” She also claimed to witness her roommate “passed out in the dorm’s elevator,” an “over-drugged” student leap out of his dorm room on the sixth floor, and she claimed that the new trend of smoking marijuana caused her clothes to “smell of marijuana” regardless of if she participated in the usage or not. [5] Drug culture was everywhere and it started having effects on the entertainment business. “By way of TV at Woodstock” and “through the anti-war songs,” civilians started turning into hippies, who demonstrated their disapproval of the current wartime and aftermath of the Kent State shootings through this new type of music [6] Such rapid changes even affected athletics, where the largest impact was seen through “postponement of practices and contests.” [7]

The ongoing effects of the Kent State shootings and the Vietnam War left an impact on civil rights issues pertaining to women and blacks. “Widespread protests and the televising of the process became the norm,” Mackey noted. “Those who protested the war combined their efforts with those who protested in favor of increased rights for Blacks and women,” Mackey added. Campuses, such as Mackey’s, turned into “chaos” while students became “crazily radicalized over night.” [8] However, such chaos helped campuses across the United States become less strict about the rules regarding female students. “Young women no longer had to stay in separate dorms; they could live in co-ed dorms and use co-ed bathrooms.” [9] Mackey also notes how “no one kept track of their schedules or their whereabouts any longer” and “there was no longer a curfew for girls.” With fewer restrictions on females, there was an increased opportunity created for women after more and more people began protesting for what they believed in. As for blacks, changes were seen during the Vietnam War era, but were not as substantial as the progression seen in the movement for women’s rights. The first war blacks were allowed to enter the army was World War II, and by Vietnam times, “Blacks were drafted in higher proportional numbers than whites” but “were often required to do the most dangerous work.” [10] Blacks got what they wanted but were treated poorly. “Blacks also could not serve as officers,” Mackey adds. Even though “Blacks gained rights, at least in terms of the law” they were still treated with unequal and unfair opportunities in American society. [11]

Education was another visible cultural change seen throughout this era. One of the most immediate changes seen on Mackey’s campus after the shootings was that “no one went to class” and students attended “teach-ins” to learn about the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. SUNY Plattsburgh President George Angeil even allowed students to use “his office for strike-coordinating activities.” [12] Nationwide, “detrimental” effects were seen on 18% of college campuses, according to historians Richard Peterson and John Bilorusky, and “academic standards could be said to have declined or academic integrity to have been comprised” after the Kent State debacle. [13] Classes at SUNY Plattsburgh “were officially cancelled” and students were given the option to “take the grade [they] had when everything had fallen apart” or contact their professors to discuss their grades. [14] This was a nationwide effect and Peterson and Bilorusky note that in as many as one in four colleges, classes were brought to an abrupt end. [15] In the following semester, drastic changes in course content changed, as well as policies regarding dropping courses. Mackey explained how you could now “drop/change courses without a penalty” and questioning the professor “about the grade you received” was now common. [16] She also explained how by her recollection, courses “suddenly changed.” Courses started incorporating content regarding “Africa and Asia, current events, civil rights” and the “women’s liberation movement.” Courses also started incorporating “Chinese and Indian classics, world religions…and courses on what other cultures are like and…what they thought of America.” [17] Schools, such as Mackey’s, “began to study and analyze the cultures of Africa and Asia because our ignorance of such things in Vietnam.” [18]

Antiwar movements and strikes swept the nation after the Kent State shootings and the ongoing war in Vietnam. Peterson and Bilorusky state that “significant impact” was portrayed at 57 percent of American colleges after the Kent State shootings. [19] Peterson and Bilorusky also report “essentially peaceful demonstrations” on 44 percent of the American colleges. [20] Such demonstrations included “sit-ins, parades, picketing, mass meetings, rallies…and so forth.” [21] However, these peaceful protests led to threats of violence at schools such as Mackey’s. “There was a sense of urgency—a feeling that we had to get involved,” explained Mackey. “Someone came up with the idea of a march on the Air Fore Base…they were met at the gate of the base by servicemen with loaded guns who told them in no uncertain terms that if they came closer, they would be shot.” [22] The amount of student participation in antiwar movements “had exactly doubled” from January 1970 to June 1970. [23] There was such a high demand for locations to hold protest meetings that “universities bent over backwards to provide students with office space.” [24] Antiwar movements and strikes became more and more common.

During times as vulnerable as they were in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it only takes one dramatic event to spark change. The Kent State shootings created “a new wave of arson” and can be looked upon as a pivotal turning point in American culture. [25] Changes in all aspects of culture were seen: education, women’s rights, black rights, and the increased participation in antiwar movements and protests. Without the unfortunate event at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, we may not have seen such important changes in American culture.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[2] Email interview with Patricia Mackey, March 20, 2015.

[3] [Mackey] interview.

[4] [Mackey] interview.

[5] [Mackey] interview.

[6] [Mackey] interview.

[7] Husar, John. “Big 10 Coaches Feel Effect of Campus Riots.” Chicago Tribune. 18 May 1970: c2. [Historical Newspapers].

[8] [Mackey] interview.

[9] [Mackey] interview.

[10] [Mackey] interview.

[11] [Mackey] interview.

[12] Linda Charlton, “Activity Stepped Up Here: Students Move Off Campus to Widen Protest Here,” New York Times, May 7, 1970 [ProQuest].

[13] Peterson, Richard E., and John A. Bilorusky. May 1970: The Campus Aftermath of Cambodia and Kent State. (Berkeley: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1971), 25.

[14] [Mackey] interview.

[15] Peterson and Bilorusky. 16.

[16] [Mackey] interview.

[17] [Mackey] interview.

[18] [Mackey] interview.

[19] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[20] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[21] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[22] [Mackey] interview.

[23] Beggs, Daniel C., and Henry A. Copeland. “Opinion on the Campus: Students Become More Willing to Support Beliefs with Action.” Chicago Tribune. 01 August 1970: w2. [Historical Newspaper].

[24] Oliphant, Thomas. “Universities Feel Compelled to Restrict Anti-War Activities on Campus.” Boston Globe. 19 July 1970: 1. [Historical Newspapers].

[25] Brands. 170.

Leave a Reply