Southerners were not the only Americans whose lives were transformed during the decades immediately following the Civil War. Northerners did not face the same challenges of political reconstruction or economic transition in the aftermath of slavery, but they did face a series of revolutionary experiences. Students in History 118 should be able to identify the main social, political and economic forces that ripped apart the North during the 1870s and 1880s, but they should also be able to explain the story of westward expansion in great depth. That was a story of unexpected complexity, one that can be at least partially summarized through a close reading of this famous painting by John Gast, entitled, “American Progress,” (1872).

Year: 2016

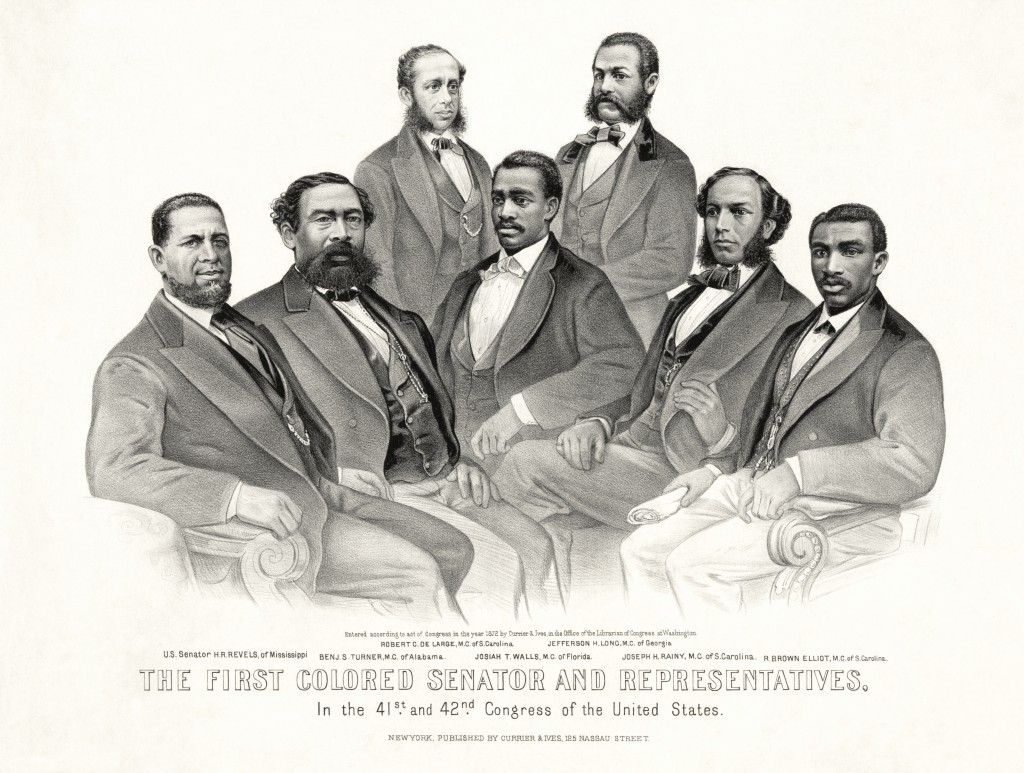

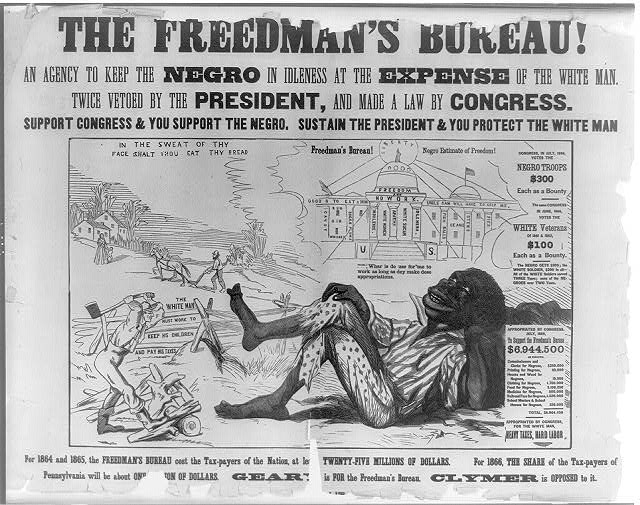

Political life in the South during Reconstruction kept changing at a rapid pace. In his book, A Short History of Reconstruction, Eric Foner charts a remarkably complicated set of factors that elevated some groups over others at different times across various states during the period between 1865 and 1877. Once Congress wrested control of the political restoration process away from President Johnson in 1866 and 1867, the result was a brief revolutionary heyday for black political leadership. Yet there was always violent resistance lurking in southern communities determined to stop participation in government by the ex-slaves. The fight culminated with the battle to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment and suppress the rise of the Ku Klux Klan across the South. This was a challenge that even a more conservative figures in the Republican Party seemed to embrace –at least at first. President Grant led the fight to crush Klan-inspired political violence –a determination that surprised some contemporaries who had voted for Grant under the slogan, “Let Us Have Peace.” Yet, even though the post-war Klan was crushed by federal action in the early 1870s, the extent of white support for black politics seemed to collapse as the 1870s drew to a close. Consider some of the following images and see if you can explain any or all of them t can be used to help illustrate important points about American political and economic life in the South during the 1870s.

Word Cloud inspired by Foner’s Short History

Black Senators and Congressmen, circa 1872

Anti-Freedmen’s Bureau political cartoon (1866):

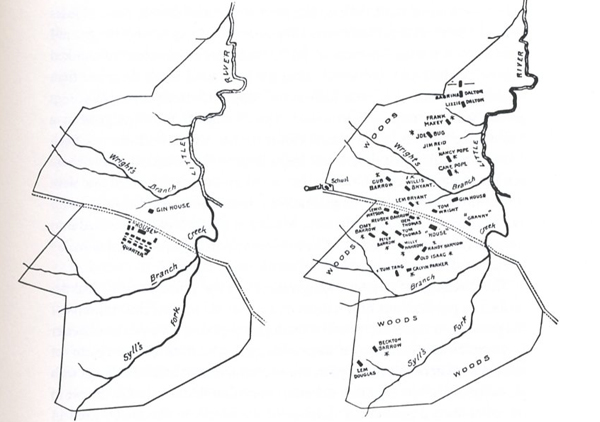

Map of the Barrow Plantation, during and after slavery:

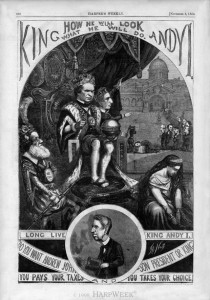

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

Eric Foner and Olivia Mahoney have created a web-based exhibition hosted by the University of Houston that is designed to accompany his published work on Reconstruction. Students in History 118 should browse the image gallery of the sections of the exhibit entitled “Meaning of Freedom” and “From Slave Labor to Free Labor” in order to immerse themselves in the images and stories of the formerly enslaved people fighting to establish themselves as free American citizens. These types of visual exhibitions sometimes are even more effective than print sources in conveying the experiences of ordinary people in the past. What does this exhibit reveal about the everyday life of Reconstruction for the freed people?

Prince Rivers (1822-1887)

The story of Prince Rivers embodies many of the insights which Eric Foner tries to convey in the opening chapters of his book, A Short History of Reconstruction (2015 ed.). Rivers was a “contraband,” a wartime runaway slave, who fled behind Union lines along the South Carolina coast in 1862. He joined the Union army, serving in one of the first all-black regiments, and became something of a wartime celebrity. Later, during post-war Reconstruction, he became a political figure in South Carolina. The sad ending to his career, however, suggests how, as Foner put it, Reconstruction truly became, “America’s Unfinished Revolution.” You can read about Rivers in the following two posts at the Emancipation Digital Classroom. Try to use his story to punctuate Foner’s analysis about “Wartime Reconstruction” and the various “Rehearsals for Reconstruction.”

The end of the Civil War brought about the restoration of the Union and the end of slavery, but were these two objectives really one and the same? If so, does Abraham Lincoln deserve the lion’s share of the credit for melding them together? These are the types of questions that historians argue over. So did nineteenth-century Americans. One way to engage a fresh perspective on that debate is to examine what a commercial printer in Philadelphia did with a popular image following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. Here is what the image looked like that year:

Yet here is what the original illustration looked like in January 1863 when Thomas Nast first drew it for Harpers Weekly:

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

Below is a photograph taken at Fort Sumter on Friday, April 14, 1865. That was a special day for the Union coalition –a kind of “mission accomplished” moment as Col. Robert Anderson returned with a delegation of notables, including abolitionists like Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and William Lloyd Garrison, to raise the American flag once again over the fort in Charleston harbor where the Civil War had begun almost exactly four years earlier.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

That’s Rev. Henry Ward Beecher speaking on the afternoon of Friday, April 14, 1865, from what he called “this pulpit of broken stone.” Originally, scholars, using magnifying glasses, thought that William Lloyd Garrison was perhaps seated on Beecher’s left.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

It was obviously a moving, reflective moment for Garrison, one captured in this detail image above from right after the ceremony and by the little known story of his visit the following morning to see the grave of secessionist icon John C. Calhoun. You can read more about this episode here and here. Sometimes people are surprised by the stories that slip out of public memory and don’t make it into standard textbooks. The Garrison visit to South Carolina in April 1865 is certainly one of them, but another such lost tale involves a Dickinsonian named John A.J. Creswell, who was deeply involved in the final passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, which occurred in early January 1865. Here is the image that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper to celebrate that moment.

You will notice the trio of men in the lower right hand corner, obviously prominent figures according to the illustrator. We researched them here at the college and were thrilled to discover that one of them was a Dickinsonian. It turns out that these are three congressman from the Mid-Atlantic (from left to right) Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell. We used a detail from that image for the cover of our first House Divided e-book, which profiles Creswell, a Dickinson graduate and Maryland politician who became one of the nation’s most important wartime abolitionists. Yet, he’s almost completely forgotten, not even mentioned in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Lincoln” (2012), which concerned passage of the amendment. You can download a free copy of Creswell’s biography, written by Dickinson college emeritus history professor John Osborne and college librarian Christine Bombaro, here. Ultimately, that might be the best way to rediscover the drama at the end of the Civil War –by seeing old stories from new perspectives.