By Megan Triplett

In American Dreams, H.W. Brands covers second wave feminism as a largely polarizing movement. Spurred by Betty Friedan’s 1963 book The Feminine Mystique, second-wave feminists sought sexual liberation, an increased role in the public sphere, and the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would add a prohibition of gender discrimination to the United

States’s Constitution. Brands also describes the reactionary pushback of the anti-feminists. Especially in regard to the feminists calls for greater sexual freedom, members of the Christian right and others who believed in the traditional “nuclear” family, launched an anti-ERA campaign. Yet, Brands only characterizes these two opposing views and neglects to describe a middleground between the two extremes of second-wave feminism.

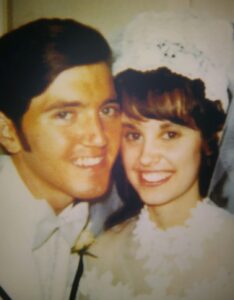

One such person who found themselves identifying with some parts from both movements was Carol Roland, later Carol Triplett, a sociology student at The University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) in the 1960s. Triplett had participated in civil rights activism in her youth, attending protests and walking out of restaurants that refused to serve African American customers. She cites her love of people in her choice to study sociology. “I wanted to get into the adoption industry,” Triplett states as her collegiate idea for an intended career, “sort of helping people, helping kids. I really liked people.”[1] Yet, Triplett only studied sociology for two years. “I enjoyed it and I did real well in sociology,” she said, “but [Lawrence Triplett] and I decided we wanted to get married before he graduated.”[2]

Because Carol Triplett chose to get married over finishing college and pursuing a career, she faced backlash that she would not have faced a generation earlier. The attitudes of second-wave feminism had begun to take their hold while Carol Triplett was in college. Her professors found difficulty accepting her decision, as they saw her as a promising sociology student. “So I know that my professors… and the counselor was very upset that I did not proceed. He (Triplett’s professor) wanted me to even go to grad school to get my masters. So he said that I thought I was brainwashed.”[3] Triplett, however, truly wanted to get married to Lawrence Triplett and start a family. “I think that, had I really wanted to be a sociologist, I would’ve stayed with it, but that wasn’t my main goal,” Triplett explains, “He (Triplett’s professor) couldn’t convince me otherwise. … I don’t regret it.”[4]

Triplett supported her female classmates as they pursued careers, but found herself more drawn to the domestic sphere. Though women of this era grew up in a climate that encouraged them to settle down, get married, have kids, and “desire no greater destiny than to glory in their own femininity,” the dictums of second-wave feminism encouraged young women to pursue careers over growing a family.[5] Yet, Triplett did not identify with the thesis

of The Feminine Mystique – that “well-educated women chronically yearned for more than their domestic lives afforded them” – though her friends largely did.[6] Triplett found no issue with her female friends who pursued a career path, and had pride in their successes. One of Triplett’s friends even joined NOW, the National Organization for Women, the group that Betty Friedan founded to advocate for women’s rights and to put the tenants of The Feminine Mystique into the political arena.

In, On Not Being Women: The 1970s, Mass Culture, and Feminism, Victoria Hesford contextualizes the feminist movement within the mass culture. This contrasts Brands, who focuses primarily on the political timeline of second-wave feminism. Hesford also distances her argument from Brands’s by pointing out that the feminist movement consisted of a collection of different people, with different backgrounds and viewpoints, people like Carol Triplett. According to Hesford, “‘women’ and ‘masses’ are present in our world as images—as representations that picture, however misleadingly, a unity that affectively solicits our identifications or disidentifications.”[7] Thus, Hesford separates her narrative from Brands by refusing to identify the feminist movement as one mass of women.

Yet, Carol Triplett could not acquiesce to her peers’ decisions to get divorced from their husbands in pursuit of this newfound liberation. Divorce became more prevalent and normalized in the late 1960s and early 1970s. When Triplett began the process of marrying her husband Lawrence (Larry) Triplett, their priest tried to ask them what they would do in the event of a divorce, but the young couple had never considered divorce an option. “The priest told us that we were the only ones that he had met that did not believe in divorce,” Triplett explains, “we said…that wasn’t even going to be in our thought process.”[8] In this way, Triplett identified closer with the views of the American right who saw divorce as “a catastrophic departure that threatens the fabric of American moral identity.”[9] Tilfer cites America’s strong link to Christianity as a foundation for this view. When her friends would seek divorces, Triplett was “very sad for them.”[10] Drawing on her Catholic faith, Triplett states, “I believe it is between them and God. I never treat them badly.”[11]

After divorcing or simply not getting married in the first place, women who subscribed to the second-wave feminism movement often devoted their full attention to their careers. When Carol Triplett encountered such people, she describes her perception of their thoughts toward her as, “ ‘oh well, we’re not interested in that, you’re not important’ ” because she chose to not have a career and to raise her family.[12] She gleaned from her interactions that “if you didn’t have a career you were nothing.”[13] Yet, Betty Friedan, a prompter and preeminent figure in the feminist movement supported women who chose to be mothers. As interpreted by Burke and Seltz, Friedan “implied that so long as women freely chose motherhood, unmedicated birth was a preferable and empowering option for labor—an extension of women’s bodily health.”[14] Activists for women’s health followed this lead, advocating for natural childbirth as a way to “recapture women’s agency while rejecting narrow, pronatalist visions of women’s identity.”[15] Thus, some feminists, like Friedan, did not reject motherhood, but sought to include it under the women’s liberation movement by advocating for natural birth. Despite distaste and shame from her peers, often shame that did not align with Freidan and other feminists, Triplett remained secure in her choice, as she “loved raising my kids.”[16]

Some took this distaste for domesticity to further levels, following the socialist feminism view that “autonomous structures of gender, race, and class all participated in contrsucting inequality and exploitation.”[17] This group “expanded the Marxist notion of exploitation to include other relations in which some benefited from the labor of others, as, for example, in household and child-raising labor.”[18] Thus, the struggle for women’s rights was inherently linked to the struggle for class-equality in the eyes of socialist feminists, who viewed content housewives like Triplett as inherently downtrodden laborers.

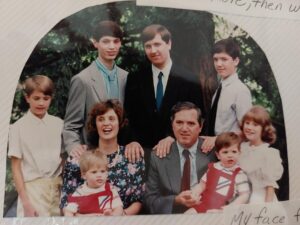

Despite her convictions to raise her family, Triplett also recognized pressure from her husband Larry to remain within the domestic sphere. “With… my marriage,” explains Triplett, “we had definite roles. He did not do any of what was called ‘women’s work.’ He didn’t do any of that. And I felt like, if I wanted to work, I would just be exhausted, having to do all that plus go to work.”[19] Triplett’s husband Larry conformed to traditional ideals and refused to take on more responsibilities in spite of the overall changing attitudes toward gender roles within the family. While raising her seven children, Triplett remarks that she “didn’t feel too bad about it [not pursuing a career] … because, actually for daycare … it would’ve cost me more probably than what I could earn.”[20] Though “agitating for affordable child care was a priority of many women’s liberation groups,” Triplett and others found themselves unable to justify pursuing a career against the costs of child care [21].

Courtesy of Carol Triplett’s Private Collection

Carol Triplett raised her seven children, six sons and one daughter, differently than her generation had been raised. “More and more women were working, so I told my boys ‘if your wife is working, you better help her out!’ I taught them how to do their own laundry and how to scrub floors and wash dishes. They would cook.”[22] In contrast to her husband’s attitude, Triplett states, “I felt like they should never feel like any job was below them.”[23] After the last of her seven children went to school, Carol Triplett took on a job as a second grade teacher’s aid. In working, Triplett realized the extent of what working mothers had taken on. “At that time, I thought ‘oh my goodness, how could they do everything?’ You can’t do everything.”[24] She concluded that “the man has to take on some of the responsibilities” and reflects that “things changed that way and for the good.”[25] Regardless of Triplett’s choice to happily raise her family, she raised her sons in the context of second-wave feminism to have a different attitude towards housework than her husband.

Tensions heightened after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, which legalized abortion throughout the United States. Triplett, who was a faithful Catholic, went “against the culture” as she “didn’t see killing a baby to be God’s best.”[26] The Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade isolated Triplett from the feminist movement, and linked her, on this one issue, with the emerging anti-feminist movement. According to Brands, “Phyllis Schlafly’s conservative Eagle Forum added STOP ERA to its name, and its spokespersons argued that the equal rights amendment would deprive women of traditional distinctive rights, such as the right to be supported by their husbands and the right to be exempt from military service – besides being an affront to states’ rights.”[27] Though Triplett was supported by her husband and had no desire to serve in the military, she did not identify with the Eagle Forum and supported the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. Yet, her Catholic faith compelled her to stand against feminist arguments that sexual liberation and pro-choice objectives were necessary measures for women’s rights. According to Triplett, “my faith is to be lived whether the crowd agrees or not.” At one point, Triplett worked in a crisis pregnancy center, and so saw the individual struggles that the Roe v. Wade decision affected.[28] “I love these girls and I feel I can help them more to have their child,” Triplett said, “I counseled many and always respected them. I can feel for them very strongly.”[29]

Carol Triplett, a devoted wife and mother of seven, found herself aligned with both feminist and anti-feminist viewpoints. She did not pursue a career, instead contently choosing to fulfill household duties and raise her children. Triplett does not regret her decision stating, “a mother, when they’re home, they teach their children so many things.”[30] Though working peers sometimes expressed distaste for her choice, Triplett supported their choices to pursue a career and had hoped that they would support her choice to be a housewife. However, Triplett severed herself from the feminist movement on issues of divorce and abortion due to her Catholic faith. In contrast to Brands’s polarized depiction of the second-wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Carol Triplett serves as an example of a real woman whose complicated ideals did not fit the picture of feminism nor the picture of anti-feminism.

[1] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[2] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[3] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[4] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[5] Friedan Betty, quoted in H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 176.

[6] Friedan Betty, quoted in H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 176.

[7] Hesford, Victoria. 2015. “On Not Being Women: The 1970s, Mass Culture, and Feminism.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114 (4): 713–34. doi:10.1215/00382876-3157100. [America, History and Life], 715.

[8] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[9] Hilfer, Tony. “Marriage and Divorce in America.” American Literary History 15, no. 3 (2003): 592–602. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3568088. [JSTOR], 592.

[10] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[11] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[12] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[13] Interview with Carol Triplett (email), April 11, 2022.

[14] Burke, Flannery, and Jennifer Seltz. 2018. “Mothers’ Nature: Feminisms, Environmentalism, and Childbirth in the 1970s.” Journal of Women’s History 30 (2): 63–87. doi:10.1353/jowh.2018.0014. [America, History and Life]

[15] Burke, Flannery, and Jennifer Seltz. 2018. “Mothers’ Nature: Feminisms, Environmentalism, and Childbirth in the 1970s.” Journal of Women’s History 30 (2): 63–87. doi:10.1353/jowh.2018.0014. [America, History and Life]

[16] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[17] Gordon, Linda. “Socialist Feminism: The Legacy of the ‘Second Wave.’” New Labor Forum 22, no. 3 (2013): 20–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718484. [JSTOR], 22.

[18] Gordon, Linda. “Socialist Feminism: The Legacy of the ‘Second Wave.’” New Labor Forum 22, no. 3 (2013): 20–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718484. [JSTOR], 22.

[19] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[20] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[21] Gordon, Linda. “Socialist Feminism: The Legacy of the ‘Second Wave.’” New Labor Forum 22, no. 3 (2013): 20–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718484. [JSTOR], 25.

[22] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[23] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[24] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[25] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

[26] Interview with Carol Triplett (email), April 11, 2022.

[27] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 179.

[28] Interview with Carol Triplett (email), April 11, 2022.

[29] Interview with Carol Triplett (email), April 11, 2022.

[30] Interview with Carol Triplett (Zoom conversation), April 24, 2022.

“Well-educated women chronically yearned for more than their domestic lives afforded them.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams, p.176)

Interview Subject

Carol Triplett, age 71, a Catholic stay-at-home mom in the 1970s and 1980s and part-time second grade Catholic school teacher’s assistant in 1990s and 2000s. Former civil rights supporter and mother of seven children, grandmother to twelve.

Interviews

– Email, April 11, 2022

– Zoom recording, April 17, 2022

Selected Transcript

From audio:

Q. Did you go to college? What for? How long? What was it like?

A. I went to UMBC and I went two years, which I wasn’t in a two year program. So, I went two years and I was majoring in sociology. I enjoyed it and I did real well in sociology, but your grandfather and I decided we wanted to get married before he graduated. We were both the same age, so we were both going to graduate in those four years. So, instead I quit after two years, went to work for a year and then we got married during his last year of school. So I know that my professors… and the counselor was very upset that I did not proceed. He (Triplett’s professor) wanted me to even go to grad school to get my masters. So he said that I thought I was brainwashed. But, my goal was to get married and have a family. I think that, had I really wanted to be a sociologist, I would’ve stayed with it, but that wasn’t my main goal. … He (Triplett’s professor) couldn’t convince me otherwise. … I don’t regret it.

Q. What drew you to sociology in the first place?

A. I was an only child for like ten years, and then we adopted Dayna and Jimmy and I wanted to get into the adoption industry, sort of helping people, helping kids. I really liked people.

Q. What were your feelings toward divorce?

A. The priest told us that we were the only ones that he had met that did not believe in divorce…we said…that wasn’t even going to be in our thought process. … So in my generation they were starting to feel that divorce was fine and that careers were good … However when I did, later on, socialize, it seemed like if I wasn’t in a career or doing something, it’s like, ‘oh well, we’re not interested in that, you’re not important.’ … In a way, I didn’t feel too bad about it … because, actually for daycare … it would’ve cost me more probably than what I could earn.

Q. Did the women’s movement have an impact on your marriage?

A. With… my marriage, we had definite roles. He did not do any of what was called ‘women’s work.’ He didn’t do any of that. And I felt like, if I wanted to work, I would just be exhausted, having to do all that plus go to work. And I did end up going to work after the twins … started going to school. At that time, I thought ‘oh my goodness, how could they do everything?’ You can’t do everything. The man has to take on some of the responsibilities. Things changed that way and for the good.

Q. What did you teach your kids about women’s issues? I was wondering if you raised them any differently than how you were raised, if you instilled any values in them from the women’s movement that your generation wasn’t taught from a young age.

A. More and more women were working, so I told my boys ‘if you’re wife is working, you better help her out!’ I taught them how to do their own laundry and how to scrub floors and wash dishes. They would cook. I felt like they should never feel like any job was below them. … And Amy, I felt like Amy should have the chance to go to college … but she really didn’t have anything she wanted to work toward, just like I did. And she wanted to raise a family.

From email:

Q. Did the Roe v. Wade decision affect your attitude toward the feminist movement as a whole?

A. I kept my values and went against the culture. I still believe that sex is for marriage. That is Gods best and it keeps your problems down. The Roe v. Wade (decision) made me feel very out of the feminist movement. My faith is to be lived whether the crowd agrees or not. I worked in a crisis pregnancy center and did hands on help for women in trouble. I love these girls and I feel I can help them more to have their child. I counseled many and always respected them. I can feel for them very strongly. But I don’t see killing a baby to be God’s best for them.

Further Research

- Burke, Flannery, and Jennifer Seltz. 2018. “Mothers’ Nature: Feminisms, Environmentalism, and Childbirth in the 1970s.” Journal of Women’s History 30 (2): 63–87. doi:10.1353/jowh.2018.0014. [America, History and Life]

- Dawn Ann Drzal. “Casualties of the Feminine Mystique.” The Antioch Review 46, no. 4 (1988): 450–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/4611947. [JSTOR]

- Gordon, Linda. “Socialist Feminism: The Legacy of the ‘Second Wave.’” New Labor Forum 22, no. 3 (2013): 20–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718484. [JSTOR]

- Hesford, Victoria. 2015. “On Not Being Women: The 1970s, Mass Culture, and Feminism.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114 (4): 713–34. doi:10.1215/00382876-3157100. [America, History and Life]

- Mann, Susan Archer, and Douglas J. Huffman. “The Decentering of Second Wave Feminism and the Rise of the Third Wave.” Science & Society 69, no. 1 (2005): 56–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40404229. [JSTOR]

Leave a Reply