By: Kathleen Donovan

Link to Video: https://youtu.be/xyGAMLw8UVU

The year was 1972. Colonel (Retired) John V. Donovan, just a 22-year-old corporal at the time, had just returned home from a two-year deployment to an active combat zone in Vietnam not one year earlier. Shortly after returning home, he was quickly ushered into college, where his new advisor at the University of Massachussetts at Amherst told him “Don’t you ever sign up for one of my classes because you will be depriving someone of an education.”[1] Donovan replied “You’re the most closed-minded individual I’ve ever encountered, and you can kiss my ass!”[2] Amidst struggling to return to civilian life– dealing with PTSD– he was also directly faced with intense waves of protestors in opposition to American involvement in Vietnam (1955-1975). These protests began in 1965, around the time when President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated the war and continued into the 1970s.[3] Although Donovan enlisted to support the war effort for “patriotic reasons, not political ones,” he disagreed with the protests, which were largely targeted at University ROTC offices and officials, feeling as though they grouped veterans in with the government that was promulgating the violence in Southeast Asia.[4]

Although H.W. Brands details of the intense social movement of Vietnam War protesters in his book American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, focusing on their magnitude and in turn, their effect on the government, Brands does not adequately capture the true nuance of these protests, and how they impacted a particularly vulnerable population: Vietnam War veterans. Brands offers a soldier’s account of the combat they endured, but again, only marginally acknowledges how the war, and the protests, affected them beyond their tours. Donovan supplements Brands’ account by provides key insights into the nuances of both the protest movements and how they affected veterans in everyday life.

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated the decade-long conflict in Vietnam into a full-fledged war after the Gulf of Tonkin incident and subsequent Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, allowing him authority to direct military action against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese.[5] In theory, the US wanted to prevent communism from expanding to countries neighboring Russia and ultimately dominating the world, or the Domino Effect. This action was so controversial, particularly after Johnson’s escalation, because many Americans did not see US involvement as necessary. In fact, many saw it as overextending influence, resources, and American lives to a conflict they believed the US had no business being in. Others claimed that it was morally wrong.[6]

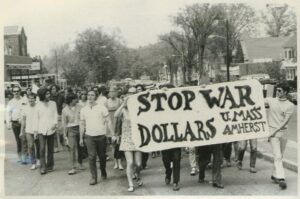

The Vietnam controversy prompted unprecedented protests nationwide. A number of these demonstrations were within cities, such as a march in New York City in the spring of 1967 as well as another march on the Pentagon in the fall of 1967.[7] These protests contained individuals from nearly all walks of life: “Student radicals rubbed shoulders with clergymen; counter culturists shared leaflets with white-collar managers; celebrity authors shook hands with military veterans of the Vietnam War itself.”[8] This description not only captures the diverse range of individuals who disagreed with the war, but it also hints at how some veterans even disagreed with the war– the only instance in which Brands discusses effects on veterans. Brands emphasizes how these protests were directed at the government, but Donovan recalls how he and his fellow vets felt that they were also the subject of these demonstrations.[9] In fact, the veterans directly experienced the gravity and fire of the protesters arguably more so than the government, as the majority of protests took place away from the direct presence of the government.[10] College campuses, environments dense with young veterans granted funding for their education through the G.I. Bill, became a setting in which many of these protests took place.

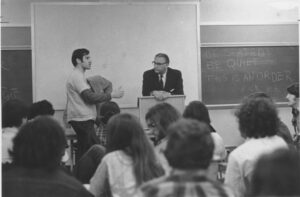

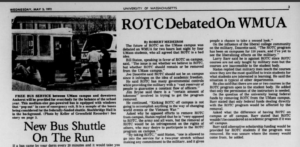

Donovan was one of these veterans. He recalls the swaths of protesters covering the campus with signs condemning the violence and demanding peace.[11] Due to the unique nature of the campus environment, teach-ins became a popular mean of demonstration.[12] Additionally, college ROTC offices became the target of many protester’s grievances. In 1970, protesters at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (UMass-Amherst) demanded that the ROTC at UMass be abolished, and a daycare center established in its building.[13] The opposition argued that if the US needed military leaders, they should at least remain on campus so that they are educated and exposed to the movement for peace.[14] These protests continued for years to come.

In 1972, students and faculty occupied ROTC buildings to commandeer space for teach-ins qualifying the amorality of the war.[15] On April 27th, 1972, the university newspaper The Daily Collegian reported that the Faculty Senate had decided to disqualify any ROTC courses from counting towards credits.[16] Donovan recalls how this directly affected him: he had taken classes in military training whilst serving, and those credits, that had initially counted towards his requirements, were all the sudden stripped away. He remembers the frustration he had, as not only was he ostracized from campus for being a veteran, making it even harder to adjust, but the credits he did have were suddenly being ripped away, as was a portion of his academic progress, thus further adding obstacles to positively adjusting. However, these unwelcoming messages were not isolated to protests and public spaces.

Donovan emotionally recalled how this tension extended into his own household. He recalled how his older sister, a staunch anti-war protester herself, was dating a fellow anti-war ‘conscientious observer’. One day, Donovan’s sister was talking about her disapproval of the war, to which their mother asked “Well, what if Jack died over there?” to which his sister and her boyfriend replied, “You know, well, that was his choice.”[17] Although they later reconciled, this interaction captures the intense polarization at the time, not even giving sympathies to family at times. The morality of the Vietnam War became so intense that

Another medium of protest that Brands does not talk about is the vast collection of music written directly in protest to the Vietnam War. This form of protest was so effective because it was able to permeate so many areas of life and further popularized the peace movement through accessible means.[18] Songs such as Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind (1962) and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On (1971) conveyed the messages of the protesters of peace movement through popularized, digestible means. These songs contained lyrics such as “How many times must the cannonballs fly before they’re forever banned?/ How many times can a man turn his head and pretend that he just doesn’t see?/ How many deaths will it take ‘till he knows that too many people have died?”[19] Dylan’s lyrics directly call listeners both condemn the violence and ask themselves ‘when is enough, enough?’. Gaye sings,

“We don’t need to escalate. You see, war is not the answer. For only love can conquer hate.”[20] In this song, Gaye both calls to the government, condemning them for the escalation via the Cambodian Incursion in 1970 and evokes the spirit and mission of the peace movement, asserting that love, not violence, will quell the issues of the time.[21] Donovan tried to avoid this type of music in the Vietnam era, although he could not avoid listening since they were so popular. “To this day, when I hear her voice, I cringe,” he laughed talking about singer Judy Collins.[22] He elaborated that his distaste for her was because her music conveyed her “anti-war stance, but worse, her anti-military stance.”[23] This highlights the blurry lines within the protests.

Some protests, of all mediums, were condemning the war; some were condemning the broader violence brought by the war, emphasizing the need for peace. Others, however, included anti-military sentiment, such as the songs of Judy Collins and the ROTC protests at UMass-Amherst, as student protesters asserted that ROTC was intricately connected with the military.[24] Donovan, who like other veterans somewhat agreed with aspects of what some protesters were opposing, believed that “You could be against the war politically, militarily, whatever, socially, but you cannot be against our soldiers, sailors, airmen, marines who are fighting that war.”[25] In conclusion, these unprecedented protests took effective hold on the nation, overall affecting veterans’ just as much, if not more, than the government at which the demonstrations were directed.

The Vietnam War inspired unprecedented protests that took many forms– demonstrations, personal interactions, music, and more. These protests varied in goals, from peace to anti-military, but shared overall objectives of pushing the government to consider ceasefire and peace. Brands skims over these nuances of the protests in his survey of the time, however, by looking deeper into veterans, and how veterans were affected by these protests, can provide further insight into the complexities of the time.

[1] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 7, 2025.

[2] Ibid.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The Unites States Since 194 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 152.

[4] Brands, 154.

[5] Brands, 136.

[6] Brands, 152-154.

[7] Brands, 154.

[8] Brands, 154.

[9] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 7, 2025.

[10] Brands, 154.

[11] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 7, 2025.

[12] Brands, 154.

[13] Robert Mendeiros, “ROTC Debated on WMUA,” The Daily Collegian, Amherst, MA, May 6, 1970.

[14] Ibid.

[15]The Daily Collegian, Amherst, MA, April 21, 1972.

[16] The Daily Collegian, Amherst, MA, April 28, 1972.

[17] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 7, 2025.

[18] D.E James. “The Vietnam War and American Music: Sex, Terror, and Music.” Social Text, no. 23, (1989): 122–43.

[19] Bob Dylan. “Blowin’ in the Wind.” The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Columbia Records, 1962.

[20] Marvin Gaye, “What’s Going On,” What’s Going On, Motown Records, 1971.

[21] Brands, 170.

[22] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 7, 2025.

[23] Ibid.

[24] The Daily Collegian, Amherst, MA, May 1, 1970.

[25] Video Interview with Col. (Ret.) John V. Donovan, Carlisle, PA, and Chapel Hill, NC, April 8, 2025.

Appendix:

Excerpts from Interview Transcript:

So the first question is, what did you think about the war before you enlisted?

I didn’t have that much of a political angle on it, as I did it from a patriotic angle. I wanted to serve my country, and, I believed in my duty and I chose to make that sacrifice and that contribution to my country.

Wow. So your parents were, it sounds like, more so thinking “We don’t want our son to be hurt”?

My mom didn’t want to lose her son. Now, the other thing you need to know is that my sister at the time, also in college, she was very, very active in anti-war peace movement– anti-military, anti Vietnam, and her boyfriend at the time, was calling himself a conscientious objector. But a very interesting statement he made, or my sister made on behalf of him. She came down to visit on a weekend, and on behalf of her boyfriend at the time who was thinking about calling himself a conscious objector, my parents said, “Well, you know, you have a brother that’s most certainly going to go, me, and Dan will probably go. What do you have to say about that?” And she said, “Hey. That’s their decision.”

Why was going straight to college after coming back from combat ‘maybe not the right thing to do’?

Well, there was no readjustment at all. I mean, I got home. I just found a place to stay by myself. I didn’t know anybody in the school. And then, and my classmates, there are a lot of veterans, which helped because at least you have somebody to kinda talk to, but no group sessions or anything like that. But he knew guys that that that knew what you knew, and you could relate to them. Then there were, a bunch of them just those little kids that, you know, had never had a bad day in your life. And then, you know, you’re trying to assimilate into the dating scheme and all that kind of stuff. And then and trying to do some schoolwork, and you’ve been out of school for a couple of three years. And the great student that I had been in high school, not. And, you know, and I gotta figure out what I was gonna do with my life. So that’s what I was faced with, right up front. Yeah.

What were some experiences you had coming home from the war that stuck with you?

But did people spit on me? No. That never happened to me. Was I treated poorly because of where I had been, what I had done, and what I was going to be doing again? Yes. Absolutely. The most pronounced one is after two years at community college, transferred to the University of Massachusetts is kind of a given that you get in there. I was a political science major, and then August, you have to go up and meet your academic advisor. And I went in to see my academic advisor, who was a PhD and had never done anything outside of academia.

So in my opinion I didn’t know this till afterwards, he lacked a lot of, worldly experience, probably a very smart guy in the class classroom, but he was interviewing me. And he said, “So what are you gonna do with this degree of political science?” I said, “Well, I have given a lot of thought, and I’ve analyzed different options, things I thought I’d be good at, things I think I like, things I don’t wanna do. And I’m going to rejoin the military, and be an off an infantry officer in the army because I believe I can do better than what I had experienced when I was in the Marine Corps.”

And he closed his book, and he said, “Don’t you ever sign up for any of my classes because you are depriving someone of an education.” And I said, “But, you teach one of the basic, required courses, the core course I had had to take? Now you’re saying I can’t take your course?” He said, “That’s right. I will not let you. I will not let you in my classroom”. And so you’re supposed to say, “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’ll do whatever you want.”

No. Again, being myself, I stood up, and I said, “You’re the most closed-minded individual I’ve ever encountered, and you can kiss my ass!” and I walked out. And I changed my major. I changed my major fifteen minutes later to physical education.

What’s interesting is that, like, when I was doing my research last night, like, anti-ROTC protests kept popping up, but I was thinking to myself, “Who are you really hurting by taking away the ROTC? Are you sticking it to the man and the government and rejecting it for the principle? Or are you hurting veterans who came back from the war who were trying to get back to normal life?

Let me tell you another story. Remember I said that the the the guy that was the commandant of the ROTC cadets, who was a captain, who lived down the end of my street, and we used to drink beer and watch football and everything? He had just come back from Vietnam. Now he’s teaching ROTC. And when the students took over the ROTC Building just before I got there. It was the springtime.

I arrived in August, like I said. When I took over the RTC Building, they wouldn’t let anybody first of all, he couldn’t wear a uniform on campus. The students wouldn’t let him. They would become violent. These are these peacenics becoming violent. So Bill, as a captain, had his uniform on and said, “I’ll be damned”. He’s a maniac. He said, “I’m going to my office.”

And he walked into the building, and all these students are screaming and yelling. He put his hands up, and he’s a very cool, calm customer anyway. He’s an artillery officer. And he said, “Stop. Stop.” He said, “What’s your what’s your issue? What’s your theme?” And they said, “Oh, we’re so against the war.” He said, “Wow. So am I. And I went there, and I came back, and I’m still against the war!” He said, “But I’m a patriotic American, and I’m serving my country, and you can’t fault me for that.” And they let him pass and go into his office and work.

Bibliography

Grant, Lenny. 2020. “Post-Vietnam Syndrome: Psychiatry, Anti-War Politics, and the Reconstitution of the Vietnam Veteran.” Rhetoric of Health & Medicine 3 (2): 189–219. https://doi.org/10.5744/rhm.2020.1007.

Heineman, Kenneth J. 1992. Campus Wars : The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era. New York, NY: New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814744802.

Nicosia, Gerald. (2001). Home to war. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

The Daily Collegian [Amherst MA] 20 April 1972 – 1 May 1972. Print.

The Daily Collegian [Amherst MA] 24 April 1970 – 14 May 1970. Print.